Gorbachev’s Nobel Peace Prize: A symbol of hypocrisy in the face of Azerbaijani bloodshed Black January in focus

On October 15, 1990, it was announced that Mikhail Gorbachev, then President of the USSR, had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Norwegian Nobel Committee justified this decision by highlighting Gorbachev’s “leading role in the peace process which today characterizes important parts of the international community,” acknowledging his efforts “opens up new possibilities for the world community to solve its pressing problems across ideological, religious, historical and cultural dividing lines.”

One might question whether the authors of this justification would reaffirm their words today, as innocent blood continues to be shed across the globe, with entire cities—children included—being obliterated in what increasingly resembles a clash of civilisations. Yet, this reflection is not the core of the matter. Our purpose in revisiting this event is entirely different. Before revealing it, however, let us consider another dimension of the discussion.

A few years after receiving the award, Gorbachev admitted that the perception of his Nobel Peace Prize within the USSR was "far from civilised or dignified." He attributed this to the fact that, in the past, the awarding of prizes in literature to Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn had occurred under circumstances that highlighted their dissident stances, which were perceived in the USSR as anti-Soviet provocations. Consequently, "only awards for achievements in the exact and natural sciences were taken seriously, and even then only within academic circles."

However, Gorbachev evaded the truth, attempting to obscure the historical reality behind the USSR population's rejection of his Nobel Peace Prize in a "dignified" manner. The figures of Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn had nothing to do with this rejection. The core issue was that Gorbachev received this prestigious award with bloodstained hands—without quotation marks.

For the same reason, it is impossible to agree even slightly with the Nobel Committee’s assessment of Gorbachev's activities during that period. Their press release spoke of a "peace process" and alleged prospects for resolving profound global issues through the near-erasure of cultural and religious differences.

Let us take another brief excursion into recent history. At the beginning of his lecture as a Nobel laureate (Oslo, June 5, 1991), Gorbachev expressed his excitement, noting that "on similar occasions great men addressed humankind – men famous for their courage in working to bring together morality and politics. Among them were my compatriots." He then urged the audience to reflect on what seemed to be a simple and clear question: "What is peace?" Defining ideal peace as "the absence of violence," Gorbachev claimed that his Nobel Peace Prize represented recognition of his commitment to peaceful means in the implementation of the perestroika agenda.

One might wonder if Gorbachev himself believed in what he said, especially in light of the violence he sanctioned during the January 1990 events, when the Soviet army, on his orders, unleashed a violent crackdown in the Soviet city of Baku. Of course not, as he was well aware of what had happened in Azerbaijan. But even at that stage, he sought to obscure his complicity in the bloody chaos in Baku, which led to the deaths of innocent Azerbaijani citizens, among whom were not only Azerbaijanis but also Jews, Russians, Tatars, and Lezgins. Without any qualms, Gorbachev spoke of "peaceful perestroika." Similarly, the Nobel Committee representatives, with no pangs of conscience, awarded the Peace Prize to a politician whose hands were stained with the blood of innocent Azerbaijani civilians.

Beginning

Now, to confirm the points made above, let us recall the last quarter of the 20th century.

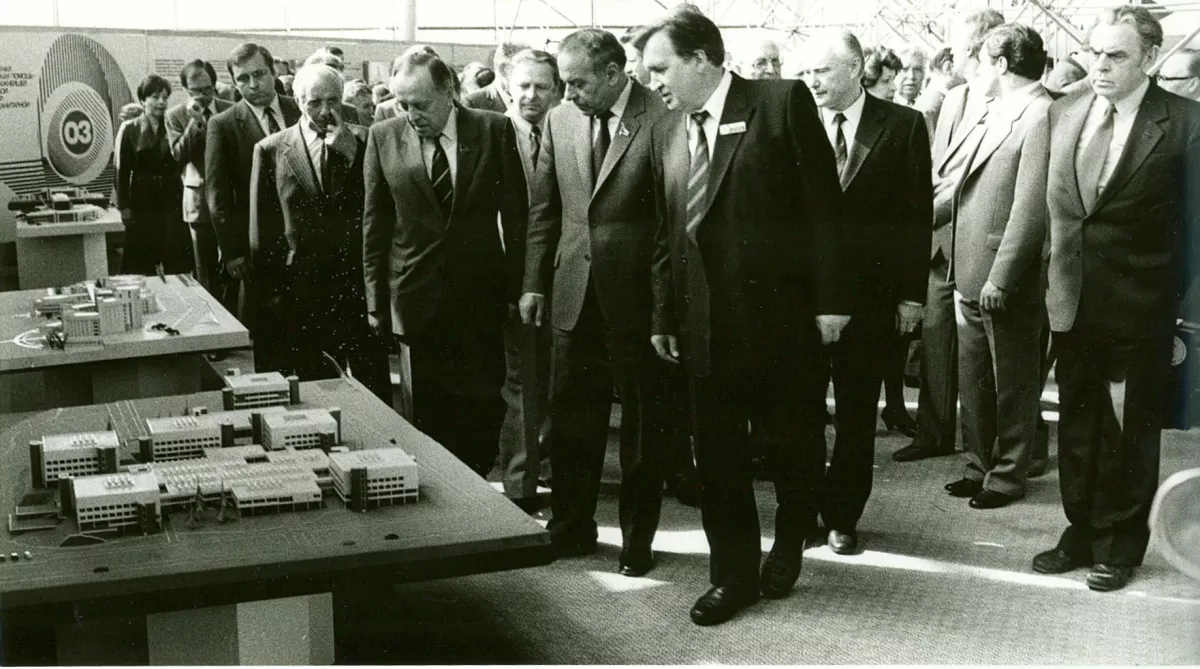

Nurtured by the Armenian mafia of Stavropol, Gorbachev hated Azerbaijan and everything Azerbaijani with all his soul. In his 1995 book Life and Reforms, he does not conceal that, at the November 1982 plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, following Brezhnev’s death, he asked the new General Secretary Yuri Andropov about the reasons for the appointment of Heydar Aliyev as a new member of the Politburo. Russian journalist Alexander Trushin writes that upon seeing “H. Aliyev, M. Gorbachev had difficulty hiding his irritation.” And as soon as he assumed the position of General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee in 1985, he unleashed a wave of troubles upon Politburo member H. Aliyev, who as the first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR oversaw fourteen ministries, including all transport and social sectors.

Gorbachev, "almost deliberately, awkwardly mispronounced the name of the republic, something like ‘Azebarjan’." When H. Aliyev suffered a severe heart attack and was hospitalized, he continued to hold "meetings right in the ward. It was in vain. There, in the hospital, he had to write a resignation letter."

The President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, recalls that during those days, "the leadership of MGIMO informed me that the son of Heydar Aliyev could not teach at this university for political reasons." Following this, as the president reveals, "taking advantage of the resignation of the great leader Heydar Aliyev, Armenian nationalists and their supporters in the Soviet government immediately took action. In November 1987, two weeks after Heydar Aliyev was removed from all positions, Armenian nationalists raised their heads. The Soviet government appeased them, and in both Nagorno-Karabakh and the then-Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, another crime against our people began. Azerbaijanis were deported from their historical homeland — Western Azerbaijan, and we know this story well, we remember it."

The tragedy of January 20, 1990

Then, Gorbachev and his associates began making efforts to suppress the developing national liberation movement in Azerbaijan, using various tactics to achieve their goal. The culmination of these efforts was the tragedy of January 20, 1990.

Let us recall that at 19:27 on January 19, as a result of an explosion at the Azerbaijani television station, Azerbaijan was effectively cut off from the world. Independent military experts from the Soviet public organization "Shield," following a thorough investigation of the events in July 1990, established that the energy block of the "television and radio centre was blown up by a special Soviet Army or KGB group."

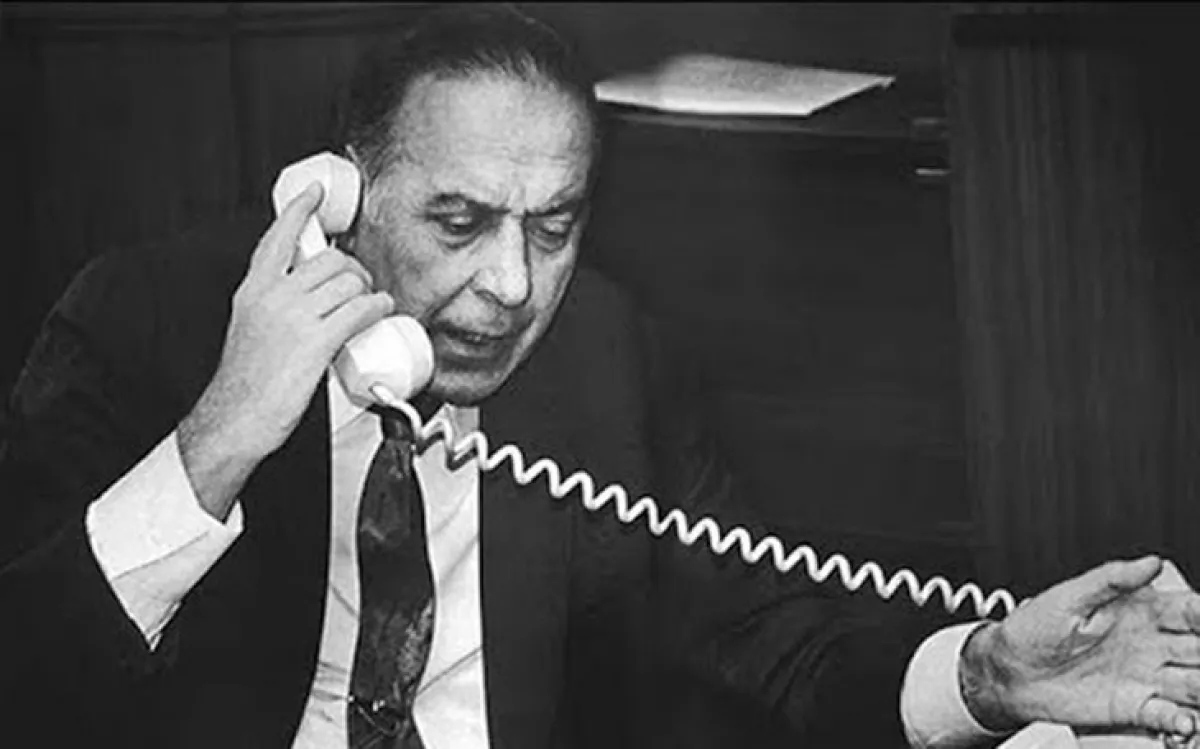

Heydar Aliyev recalled that on January 19, 1990, he "unexpectedly received a call from Gorbachev. For three years, he had brushed off my persistent requests to meet and listen to me. And it was not about personal matters – I was concerned about the events in Karabakh." However, "the former 'comrade' had refused to meet me. And suddenly, a call came: 'Things are bad in Baku, something must be done about Azerbaijan, you know,' he said in his anxious, roundabout speech. Even now, I don't understand if he was saying things were bad because I was to blame, or if he was asking for help. Then the conversation became more intense, and I don’t want to reveal the details, but we parted ways again, harshly. The most important thing is that I never could have imagined that he was calling me after having already made the decision to send troops into Baku."

As revealed by the same experts from the "Shield" organization, "the entry of troops into Baku began at 00:00 on January 20, under the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from January 19, 1990. However, the population of Baku first learned about the state of emergency from the city's commandant on the radio and from leaflets that were dropped from helicopters only at 5:30 AM on January 20, by which time the city had already been occupied by troops and blood had been shed."

In the account of film director Stanislav Govorukhin, who became effectively the only representative of Soviet intelligentsia to visit Baku in the aftermath (at the request of Ramiz Fataliyev), "the Soviet army entered the Soviet city as an army of occupiers: under the cover of night, on tanks and armoured vehicles, clearing their path with fire and sword." "I saw many balconies riddled with bullets, houses pockmarked with bullet scars," Govorukhin continues. "How could this be? After all, behind these buildings are people." Many "died in their apartments, on the balconies of their homes. The casualties would have been fewer if the people hadn't been convinced that the army, their army, wouldn't shoot at its own citizens."

In the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper from January 30, 1990, it was recorded that "in the morgue, due to lack of space on the tables, the stiffening corpses with open eyes were piled on the floor, each in whatever they were wearing, stained with clay and blood." A paramedic, "crying, lifted their shirts so that Kostya could photograph the neat bullet holes from automatic fire. Most often, the entry points were on the ribs, but one was killed by a shot to the eye, while another appeared to have half of his skull torn off by a tank. Kostya photographed a boy of about thirteen or fourteen in a short coffin."

These words also send a chill down the spine: "On the night of January 20, when the troops entered Baku, my son Alexander Markhevka was killed. He worked as a doctor in the ambulance service. He was called to treat a wounded person, and they sent Sasha. He didn’t make it. Who shot at the ambulance? The driver, seeing the doctor next to him bleeding to death, fell into a state of shock. Soon after, he fell ill and died, without ever saying a word."

Thus, the inhuman chaos authorized by Gorbachev was carried out in Baku. According to the expert evaluation of "Shield", "the armed forces of the USSR were used in Baku not to defend against external aggression but against their own people. This punitive operation was a premeditated massacre of innocent people, carried out with the use of methods prohibited by international law."

In an attempt to justify the chaos of violence, Moscow claimed it was necessary to take protective measures to prevent the creation of what it described as a potential "Islamic state" in Azerbaijan. In response, the Chairman of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the Caucasus, Allahshukur Pashazadeh, directly addressed Gorbachev, stating that "there can be no justification for the bloody massacre, the monstrous crime sanctioned by you as the head of state. The Azerbaijani people, with outrage and contempt, reject the provocative accusations made against them, which supposedly served as the reason for the deployment of troops, one of which was the so-called 'Islamic factor,' presented as a threat to the existence of the Soviet state. A country that has turned its army into a murderer of its own citizens is deserving of nothing but shame. The shots in Baku are shots at living human hearts. By sending punitive troops into Baku, where they act as occupiers, you discredited Soviet power, confirming that concepts such as sovereignty and the dignity of nations are foreign to it. You have completely discredited yourself as a political figure, proving your incompetence as the head of state. You sanctioned the murder of the people."

The factor of the National Leader

On January 21, 1990, the national leader of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, arrived with his family at the Azerbaijani mission in Moscow, where he addressed the Kremlin's anti-Azerbaijani actions, describing them as "anti-rights, foreign to democracy deeds, completely contradicting the principles of humanism and the construction of a rule-of-law state in the Soviet Union." Heydar Aliyev emphasized that if the necessary measures had been taken by the country's top political leadership at the outset of the unlawful actions in Karabakh, there would not have been the escalation of tensions or the military action that occurred on the night of January 19-20, 1990, resulting in human casualties. Describing the decision to deploy a large contingent of Soviet troops and the Ministry of Internal Affairs forces to Azerbaijan as "politically wrong," Heydar Aliyev declared that all those "responsible for the tragedy should be held accountable."

The speech by Heydar Aliyev played a significant role in sustaining the spirit of the Azerbaijani people, who were not broken by the violence. This was reflected by Vladimir Mashatin, a photojournalist for the then Soviet Union magazine, who was present during the tragic events of January 1990. In a post shared on his Facebook page in January 2020, Mashatin provided a poignant commentary along with his photographs: "The crumbling Soviet empire committed its final crimes with particular brutality. On the night of January 19-20, 1990, the Soviet army began the assault on Baku. The peaceful population, protesting the intervention of Soviet troops, was mercilessly shelled with all types of weapons. On January 22, 1990, a million (!) Baku residents took to Lenin Square to bid farewell to their fellow citizens, shot dead by their own country, their own Soviet army! The people of Baku and all of Azerbaijan gathered for a farewell rally under the barrels of Soviet occupiers' guns on the rooftops surrounding the square and the cannons of warships that had occupied Baku Bay! When a million citizens fill the squares, all rulers turn a little pale."

In July 1990, Heydar Aliyev returned to Azerbaijan from Moscow. He revealed that he was not allowed to live in Baku, so he moved to Nakhchivan. During the parliamentary elections held in Azerbaijan in September 1990, Heydar Aliyev was elected as a deputy and soon became the chairman of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic's parliament.

On November 21, 1990, the Supreme Assembly of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (NAR) issued a political assessment of the January tragedy in Baku. The resolution stated that "punitive squads of the Soviet army, special forces, naval units, and internal troops occupied Baku and, committing unprecedented atrocities against the peaceful population, carried out armed aggression," thus making "an overt assault on the sovereign rights of the Azerbaijani SSR." Following this, all those responsible for the killing of "innocent people, including children, the elderly, and women" were named, starting with Mikhail Gorbachev. The Supreme Assembly of NAR characterized the events as "occupation politics and a well-planned military aggression," and declared that January 20th should be commemorated every year in the Azerbaijani SSR as a National Day of Mourning.

Heydar Aliyev emphasized the "great guilt of the political leadership of the Soviet Union," particularly Gorbachev, whose actions were driven by "dictatorial tendencies." According to Heydar Aliyev, after World War II, the USSR had not seen such a bloody crackdown on this scale, and it was carried out by the Soviet army.

In his time as the president of Azerbaijan, the Milli Majlis (National Assembly) resolution of 1994 clarified that the objective of the "Soviet armed forces entering Baku" was "to suppress the growing national liberation movement in Azerbaijan, crush the faith and will of the people who had embarked on the path of building a democratic, sovereign state; humiliate national dignity; and demonstrate the power of the Soviet military machine to any people who dared to take this path." This led to the "ruthless destruction of unarmed people," who had taken to the streets to defend truth and justice, through "armed aggression and crimes committed by the totalitarian communist regime against the Azerbaijani people."

The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Gorbachev

The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Gorbachev in 1990 will certainly evoke outrage from those familiar with these documented testimonies. It is a shocking fact, one might even call it an affront to the feelings of the Azerbaijani people, who endured a horrific bloody massacre under Gorbachev's personal orders.

It is indeed a bitter irony that Gorbachev, who was responsible for the violent crackdown in Baku, was presented in the West as a "peace dove." This portrayal should not be entirely surprising, given the constant applause from political leaders who were presented to the world as enlightened and morally impeccable defenders of democratic norms and human rights. For example, U.S. President George H. W. Bush effectively justified the punitive Soviet military intervention in Baku, stating during a meeting with newspaper editors at the White House shortly after the tragedy that "Gorbachev handled an extremely difficult situation very well. I think he did a great job." Similarly, U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, in response to a question in Parliament about ethnic issues in the Soviet Union, expressed support for the Soviet leadership’s course of perestroika, despite the difficulties faced along the way.

So, according to them, Gorbachev "handled it wonderfully"—and no other interpretation was considered.

Are we not witnessing today a similar situation, not just double, but triple standards from the West regarding independent Azerbaijan? And are not the Western political leaders, who describe their countries as a blooming “garden" while labelling the rest of the world as "jungles," the first to violate international law, while merely claiming to champion the rights and freedoms of citizens?

Thus, Gorbachev became a laureate of the Nobel Peace Prize on the blood of the Azerbaijani people. However, he was unable to stop Azerbaijan's progress and development. Unlike the USSR, which has now vanished, Azerbaijan, having overcome numerous obstacles and artificial barriers created by external forces, has strengthened and today confidently moves towards new geopolitical heights!