The ferocious grin of neocolonialism France and the Netherlands cling to the past

Just a few years ago, when protests erupted in France's overseas territories, many people first learned that colonies still exist in the modern world. Some countries, which consider themselves "enlightened powers," are not only unwilling to part with them but also struggle to make any concessions to the indigenous populations.

We also learned that some African countries are only formally independent, while in reality, they are brutally exploited by European powers through control over the economy, financial systems, and corrupt elites. During the Soviet era, much was written and said about neocolonialism, which replaced the classic "white man's burden." However, in Eastern Europe, for the past thirty years, it has been uncommon to question the good intentions of the "Western partners."

Why, then, are countries of “Old Europe,” particularly France and the Netherlands, so reluctant to fully break away from a past they occasionally condemn, albeit half-heartedly?

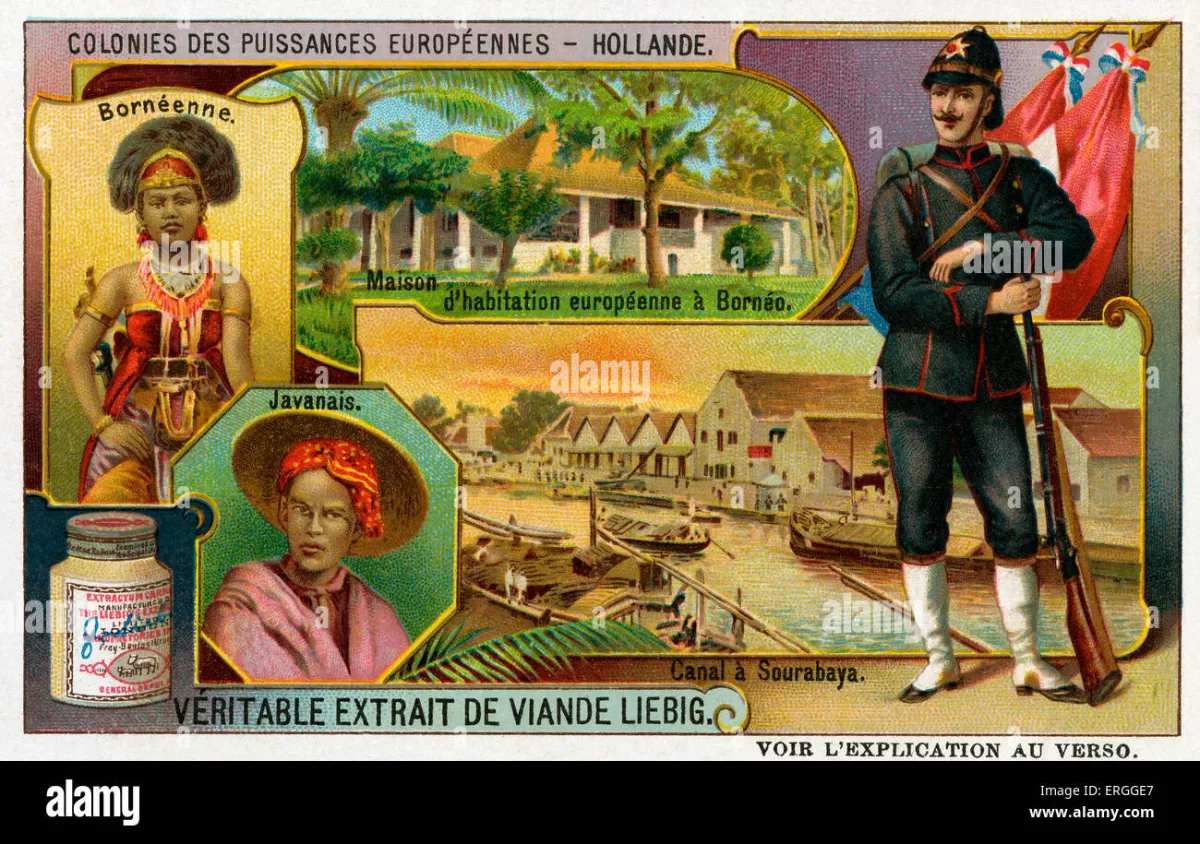

First and foremost, it is important to understand that while decolonization began only after World War II, just about 80 years ago, the European colonial tradition spans several centuries. France joined the colonial race in the 16th century, while the Netherlands, then part of the Habsburg Empire, began as early as the 15th century, right after Columbus’s discovery of America. For centuries, the French and Dutch believed they had the right to conquer and exploit other peoples—first because they had the “true faith,” then because they were the “superior race,” and later because they represented the “one true democracy.”

Less than a century ago, French President Gaston Doumergue declared that “the expansion of our colonial empire is not only our duty, but also an opportunity to strengthen France's position on the international stage.” The eminent French historian and philosopher of the 19th century, Ernest Renan, believed that “France must expand its borders and exert influence on the world in order to develop our culture and civilization.”

The second reason for the imperial complex of France and the Netherlands lies in the events of World War II. In 1940, these nations suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Nazi Germany, despite the fact that their armies outnumbered those of the Third Reich. Paris and Amsterdam were occupied by the Nazis, and it was only several years later that the Resistance forces began to form, primarily in the African colonies of these countries. The core of the "Free France" forces that liberated France in 1944 was made up of Algerian and Moroccan divisions, a fact that was deliberately suppressed for many years. This led to the creation of a myth after 1945, where the French government portrayed the empire as the “saviour of the country” and believed that only by retaining its colonies could the republic maintain its place among the great powers. This mentality resulted in bloody wars in Indochina and Algeria, costing millions of lives in those countries.

Finally, unlike Nazi Germany, France and the Netherlands did not suffer a formal defeat in the war. The colonial regimes they established were not condemned on the international stage. The process of dismantling the remnants of the past did not go beyond the withdrawal of troops from the colonies; however, the political institutions and individuals who had carried out colonial exploitation and genocide maintained their positions, and their successors continue to work in European institutions to this day.

European politicians occasionally speak of the “mistakes” of the past, but as noted by the Turkish portal Analisis, “France’s history in Africa is more than just a ‘serious mistake.’ A country that began colonization in 1524 ruled over more than 20 countries in West and North Africa. Around 35% of Africa’s territory was under French control for more than 300 years.”

Judging by the recent statements of European officials, who view their countries as a “flourishing garden” and the rest of the world as “jungles,” they seem far from repentance, similar to the process that Germany underwent after World War II or the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev. As noted by the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, “After all that, France was not denounced, neither by the European Commission, nor by the European Parliament, nor by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. This is a political hypocrisy. The European Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, two institutions that have become symbols of political corruption, share responsibility with the government of President Macron for the killings of innocent people.”

European school curricula tend to present a “balanced” view of colonial history, which, in effect, justifies European domination. As recently as 2019, sixth-grade students in the French city of Rennes were taught the “advantages of colonialism,” a lesson that the Representative Council of Black Associations in France called “unbearable colonial propaganda.” According to Middle East Eye, under pressure from right-wing and far-right forces nostalgic for the “French Algeria,” a “national narrative” is making a comeback in the school curriculum.

A similar issue exists in the Netherlands. As contemporary Dutch researcher Janne Nijman points out: “For decades, this narrative has fueled the illusion of the Netherlands as a peaceful, non-aggressive, and therefore non-imperialist country. This illusion not only concealed the reality of both formal and informal modern Dutch imperialism, but also hindered research into how international law was connected to this formal and informal modern imperialism...”

In contemporary Dutch publications on the history of Sumatra, the region is romanticized as a land with a rich historical heritage, while Dutch governors and plantation owners are portrayed as people with noble ideals who "brought civilization, prosperity, peace, and order." At the same time, official publications ignore the fact that these plantations were built on the backs of slave labor from the local population, with one in four workers dying on the plantations from harsh conditions and abuse.

Even today, these factors continue to influence the foreign policies of France and the Netherlands. As noted in a report by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: "The preservation of these former colonies as part of France reinforces its claims to be a global power with a global presence, which holds the second place in the world in terms of the area of its exclusive economic zone. The status of a great power in the ‘Indo-Pacific’ region, which in Macron’s world stretches from Djibouti to French Polynesia, is necessary to maintain and realise geopolitical ambitions of Paris which is trying to play an important role in the Western countries’ policies aimed at limiting China’s growing influence in the Asia-Pacific region."

After the explosion at the Beirut port in August 2020, President Emmanuel Macron, as a condition for providing aid, demanded that the Lebanese reconsider the provisions of the 1943 National Pact on the confessional principle of power-sharing and develop a "new contract" for the reform of the entire political system. According to the Associated Press, in an article with the telling title "Is France helping Lebanon, or trying to reconquer it? ", French authorities continue to act as though Lebanon is still under their protectorate.

Thus, the current neocolonial policies of some European Union countries have a centuries-old tradition. It is expected that, in light of the rising influence of Global South nations, the shifting of major trade flows to the Pacific region, and the emergence of the BRICS, old colonial powers now feel vulnerable. The hegemony of Europe, which lasted for over 200 years, is fading into the past, and as a result, the old empires yearn for one last decisive battle to maintain their crumbling influence.