Iran’s oppressive policies against largest minority group: Azerbaijani Turks

Human rights violations in Iran are widespread, but the government is particularly oppressive toward non-Farsi ethnic groups, an issue that demands greater international attention. Iranian Azerbaijanis make up the largest ethnic minority in Iran with an estimated 25-30% share of the general population. Those approx. 30 million ethnic Azerbaijanis, who mainly reside in northern Iran, have been enduring religious, cultural, and systemic persecution by the various governments for decades, dating back to the Shah era. Despite the onset of some political changes in Tehran and a slight easing of social restrictions, the situation for ethnic Azerbaijanis remains dire with little hope for improvement.

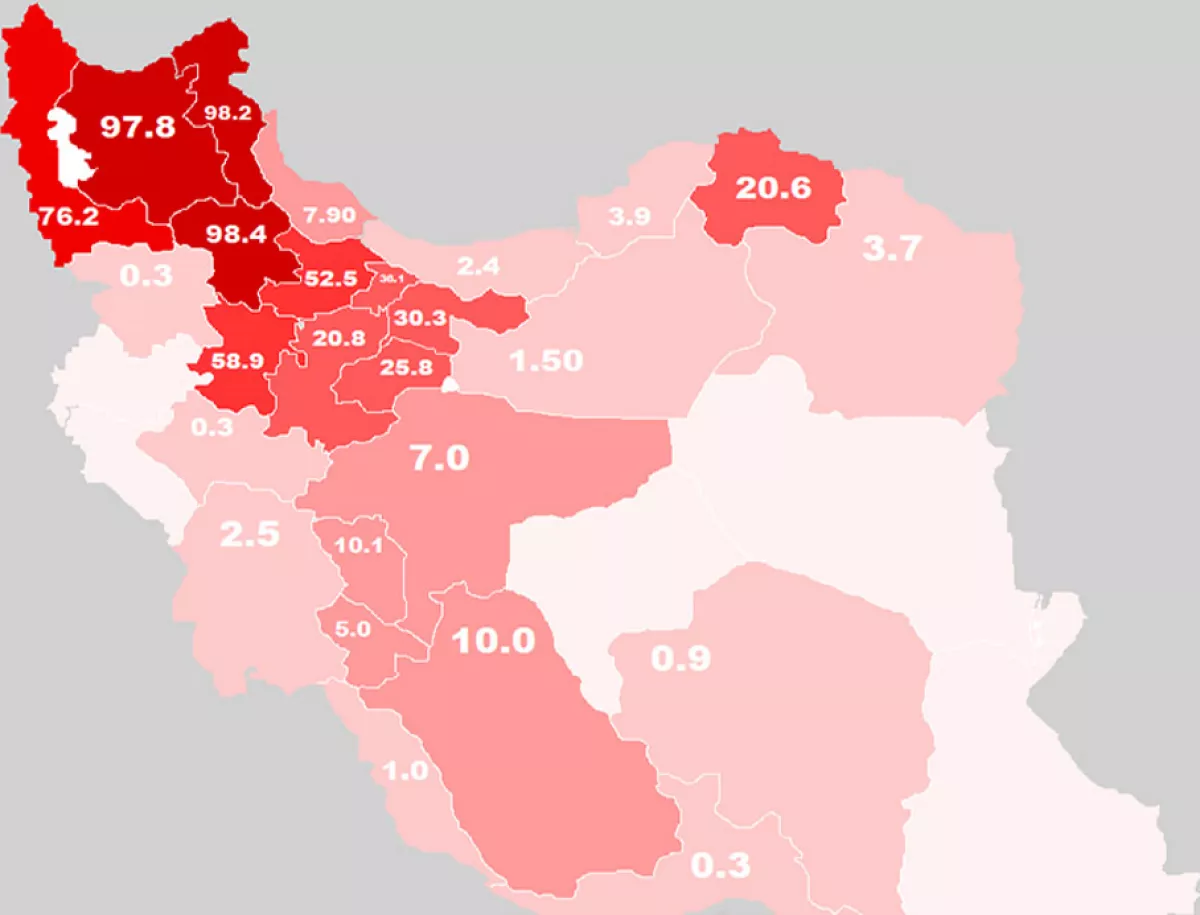

Iranian Azerbaijanis, which inside Iran are also being referred to as Azerbaijani Turks, are mainly residing in the North of the country. They live in the East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, and Ardabil provinces, though many also live in Zanjan, Hamadan, and other regions across the country (see map below of ethnic Azerbaijanis as % of population in each province by TAP Persia).

Background on the Azerbaijani Turks in Iran

The history of Iran is tightly intertwined with that of it's largest non-Farsi ethnic group. In his research paper titled "The Evolution of Azerbaijani Identity and the Prospects of

Secessionism in Iranian Azerbaijan", Emil Souleimanov recalls that Iran was almost exclusively ruled by Turkic dynasties and tribes from the 10th and 11th centuries onward, though they eventually came under strong Persian cultural influence. Rulers from the Ghaznavid, Seljuk, Timurid, Ag Qoyunlu (White Sheep Turkomans), Qara Qoyunlu (Black Sheep Turkomans), Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar dynasties were of Turkic, Turco-Mongol (Timurids), or Turco-Kurdish (Safavids) heritage, relying heavily on Turkic nobility and military forces. Until the late 19th century, Turkic remained the dominant language of the military and had long been the language of the royal court. This changed in 1925 when Shah Reza Pahlavi took power in Tehran, establishing the first exclusively Persian dynasty to rule all of Iran in near ly a thousand years and promoting a deliberate rise in Persian nationalism.

Azerbaijani Turks in Iran have historically shared a strong cultural and linguistic connection with the neighboring independent Republic of Azerbaijan. However, the XIX century Russo-Persian wars resulted in the division of historical Azerbaijan through the Gulistan (1813) and Turkmanchai (1828) treaties. This placed Southern Azerbaijan under Persian rule, while Northern Azerbaijan became controlled by the Russian Empire and would subsequently become a member state in the Soviet Union. While both regions experienced short periods of autonomy, this division weakened the nation’s political influence with the Pahlavi dynasty’s discriminatory policies only adding to this.

The Diplomatic Courier publication has dedicated an article to Iran's discriminatory treatment of this major minority group. According to the authors, the Iranian government fears that these provinces could one day seek unification with the Republic of Azerbaijan, an independent, economically robust and secular country that neighbours Iran from the North. This, combined with Tehran’s general distrust of its citizens and reliance on oppressive tactics, results in ethnic Azerbaijanis being treated as "less then" by authorities.

This concern was echoed in 2023 when members of the European Parliament referred to Azerbaijani Turks as "second-class citizens", reflecting the poor treatment they have been receiving by Tehran, and questioned the European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs on how Brussels plans to counter Tehran’s efforts to erase the historical, political, and cultural heritage of Azerbaijanis. The EU has imposed human rights sanctions on Iran since 2011, renewing them annually, but they have yet to bring any significant change.

Forms of Discrimination by Iranian authorities

Political

Azerbaijani Turks, along with Kurds and other minorities, played an active role in the mass protests following the notorious death of female student Mahsa Amini while held under police detention in 2022. The OHCHR reported that ethnic and religious minorities suffered the highest casualties and injuries during the movement. In November 2022, Azerbaijani Turks held anti-government demonstrations, during which a local medical student was killed. At the student's funeral in Tabriz, Iranian security forces allegedly attacked mourners and arrested several individuals.

Reports from international organizations detail the torture of Azerbaijani Turks in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison. Many political prisoners, including human rights activists, are also detained in facilities across Tabriz, Urmia, Ardabil, Sulduz, Salmas, and Khoy in South Azerbaijan. The article highlights that some have even resorted to hunger strikes to protest death sentences issued by the Iranian regime. Even those not involved in politics, such as rapper Reza Tabrizi and artist Murtaza Parvin, have been detained without justification. In 2024 alone, the Iranian government executed at least 901 people, including dissidents linked to the 2022 protests. While the exact number of Azerbaijani Turks among them is unknown, it is likely significant.

Environmental

Beyond political repression, Azerbaijani-majority regions suffer from environmental mismanagement. Pollution is a serious issue, with severe air pollution in Tabriz, environmental damage from mining in East and West Azerbaijan posing major threats. The Iranian government's lack of political will and the neglect of two major water sources to the Azerbaijani-majority provinces remain a vital factor for the minorities' frustration with the government.

The Aras River, which forms part of the natural border between Iran and Azerbaijan, as well as Armenia and Azerbaijan, is subject to pollution by Armenian practices. As the Diplomatic Courier reports, this has led to increased cancer rates in the Ardabil province as well as water shortages. Armenia is a long-time foe of the Republic of Azerbaijan due to it's military support to the armed separatist movement in it's Karabakh region and beyond for almost 30 years, which was defeated and expelled by the Azerbaijani military in 2020. Coupled with Tehran's historic close ties to Armenia and the political protection shield they consistently offered them throughout the period of this territorial conflict, the issue of the Aras River's pollution extends far beyond just environmental factors for Azerbaijanis.

Meanwhile, dozens of villages in East Azerbaijan and Zanjan face severe water shortages. According to an article by Eurasia Review, the Lake Urmia that is located between the provinces of East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan the Northwest of the country has lost 95% of its water over two decades, primarily due to unsustainable agricultural water extraction driven by Iran’s push for food self-sufficiency. While climate change does play a role, government mismanagement and failed restoration efforts have fueled public outrage, leading to protests and arrests.

Cultural

Cultural repression remains a major issue. Azerbaijani Turks are prohibited from learning their language or history in schools. During the 57th session of the UN Human Rights Council, Ms. Jaleh Tabrizi, Director of the Association for Human Rights of Azerbaijanis of Iran, noted that more than 70% of Azerbaijani students are denied education in their native language, Azerbaijani. Additionally, Azerbaijani cultural heritage is being systematically erased, either through neglect of historical sites or by replacing Azerbaijani and Turkic names with Persian ones.

Economic

The lack of economic investment in Azerbaijani-majority regions has also had severe consequences. According to an August report from the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), most ethnic minorities—including Azerbaijani Turks, Ahwazi Arabs, Baluchis, and Kurds—live below the national poverty line. Amnesty International has similarly condemned the economic disparity. In Ardabil province, for example, the poverty rate is 45.3%, and unemployment stands at 10.1%.

An earning for the relatives across Aras River

Despite all of these oppressive practices, Azeri nationalism has long been on the rise inside Iran. The Eurasia Review article's authors note that the movement was rekindled by a cultural resurgence and connection to kin abroad, coupled with an oppressive regime discriminating against them inside Iran. The collapse of the USSR and the rise of an independent Azerbaijan ignited a desire for autonomy among Iranian Azerbaijanis, fuelling a surge in nationalism which causes a headache for Tehran's authorities. According to the authors, this has been driven by two key factors: a rise in nationalist publications within Iran and increased access to satellite television and social media, which not only exposes them to Azerbaijani and Turkish culture but also offers a window into the secular lifestyle granted to the citizens in Azerbaijan and Türkiye, other social liberties and the general economic well-being enjoyed in these countries. These realities stand at a stark contrast to their poor treatment in Iran, which only emboldens their connection to their cultural and linguistic kin.

A bleak outlook

Despite a change in leadership, the outlook for Azerbaijani Turks in Iran remains grim. In May 2024, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, and other officials died in a helicopter crash due to poor weather conditions over Northern Iran when returning from a state visit with President Ilham Aliyev in Azerbaijan. A snap election followed, bringing Masoud Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon and perceived moderate, to power. While Pezeshkian has promised domestic reforms, stating in a televised debate that Iranians are “discontent with us because of our behavior,” the Diplomatic Courier records that there have been no meaningful actions or policies to address longstanding discrimination against Azerbaijani Turks or other minority groups.

By Nazrin Sadigova