Moral blindness of global powers and Baku’s sober strategy A blueprint for ethical statecraft

The ongoing global lawlessness across virtually all spheres once again underscores the relevance of Azerbaijan’s experience—manifested in the implementation of strategic objectives without harming secondary, let alone third parties. This is a case where tactical steps shape a constructive paradigm—both domestically and internationally.

This nuance is especially significant today, as various forces—be they states or international organisations—are increasingly assuming the right to decide the fate of entire peoples, countries, and even regions. Meanwhile, those entities that actually possess the authority to act tend to respond with silence or fearful hesitation. At best, these countries engage in rhetoric alone—especially in the face of blatant violations of basic human rights.

In reality, however, these issues manifest themselves solely in the external arena—when blatant violations of the basic conditions for civilian life, including the killing of women and children, are met with nothing more than a feeble rebuke along the lines of: “Guys, it’s not very nice to wipe entire areas off the map, especially when innocent people are dying.”

As a result, the perpetrators calmly and shamelessly refuse to so much as nod in acknowledgement of even a moral or ethical wrongdoing, continuing to pursue their own agenda without pause.

This raises a familiar question: what do we mean by “rights”? Or “freedom”? It appears that certain states have unilaterally donned the mantle of “rulers of the world,” deciding who gets to live where, how they should behave, and with whom and in what manner they are allowed to speak.

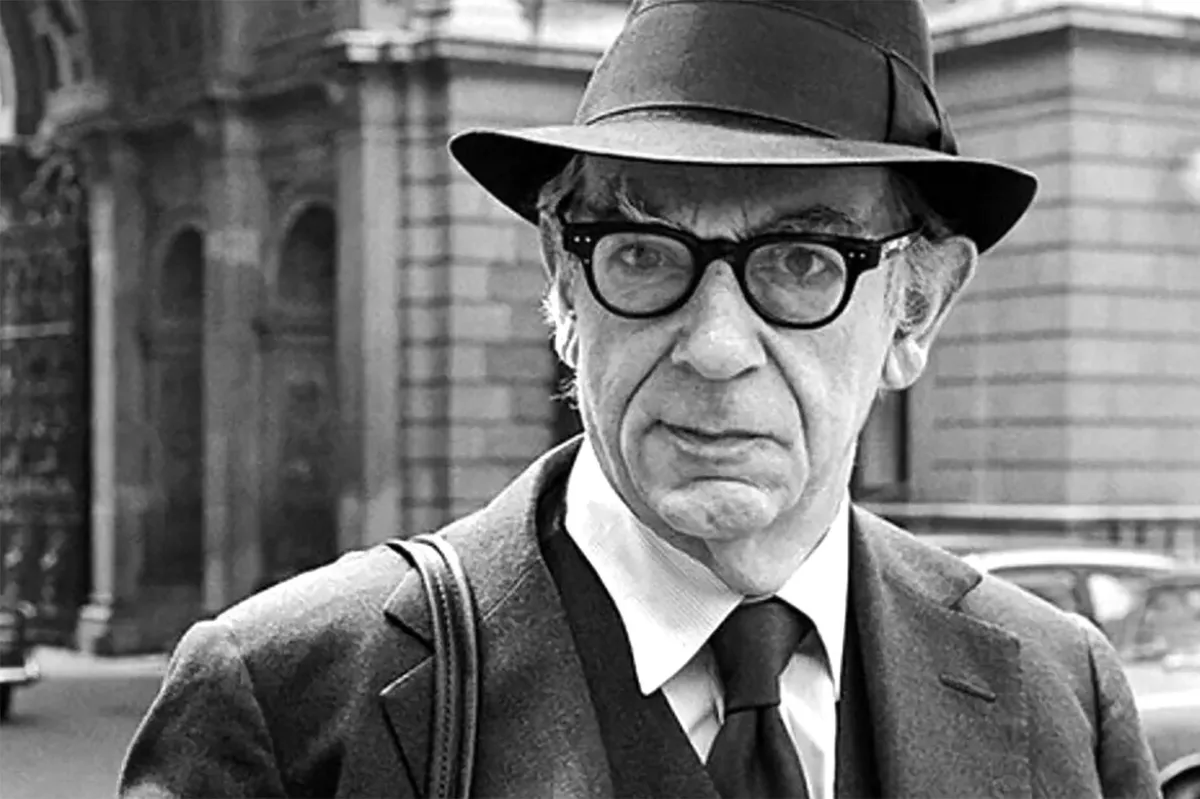

In this context, it is worth revisiting the legacy of the 20th-century British philosopher Isaiah Berlin, widely regarded as one of the founders of modern liberal political thought.

Berlin confidently argued that liberals have every reason to believe: “If individual liberty is an ultimate end for human beings, none should be deprived of it by others; least of all that some should enjoy it at the expense of others.” In determining the degree of freedom that a person or a people can exercise in choosing their way of life, a variety of other values must also be taken into account—among the most prominent being equality, justice, happiness, security, and public order. Therefore, liberty “cannot be unlimited”—especially when it leads to the erasure of entire regions populated by living human beings.

Since we’ve mentioned Isaiah Berlin’s reflections, it is also worth looking—through the lens of today—at his well-known musings on hedgehogs and foxes. Not, of course, from the standpoint of zoology or animal rights.

Referring to a line by the 7th-century BC Greek poet Archilochus — “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing” — Isaiah Berlin noted that scholars have interpreted this cryptic fragment in different ways. Perhaps it simply means that “the fox, for all his cunning, is defeated by the hedgehog’s one defence.” Berlin, however, proposed a metaphorical interpretation of the phrase, seeing in it one of the deepest distinctions between writers, thinkers — and indeed, people in general: between those who relate everything “to a single central vision, one system” through which they interpret the world, think, and feel — and those who pursue a variety of unrelated topics.

Berlin explained that the latter type, operating on multiple levels and embracing a range of disconnected experiences and subjects, do not strive to force every issue into a grand, all-encompassing — and sometimes contradictory or even fanatical — worldview.

Berlin referred to the first type of intellectual and creative personality as hedgehogs, and the second as foxes. The hedgehogs are focused on steadily resolving a primary challenge, subordinating everything else to it. Foxes, by contrast, disperse their attention across numerous directions from the outset, believing they can handle all tasks simultaneously — often disregarding the need to resolve urgent issues step by step.

From this perspective, Berlin’s classification proves insightful in the geopolitical context as well, where the disconnect between strategic approaches becomes plainly visible. In other words, while some countries (or organisations) remain focused on achieving a singular, paramount goal, others attempt to solve multiple problems simultaneously, convinced of a favourable outcome.

Yet, as developments in the Middle East and Europe demonstrate, such an approach often leads to a dead end. The absence of a unified grand strategy and the scattering of efforts across divergent directions fail to produce the desired effect — and instead trigger criticism from all sides.

Against this backdrop, the Azerbaijani experience becomes relevant once again. By formulating a national goal shared by all citizens — regardless of ethnic or religious background — Azerbaijan has successfully achieved this objective while strictly adhering to the norms and principles of international law.

The occupiers were disgracefully expelled from Azerbaijan’s ancestral lands, which had been under occupation for thirty years. What followed was a unique phase of reconstruction and revival in these regions. At the same time, Azerbaijan retained its strategic geopolitical significance as a cultural-civilisational and politico-economic hub linking East and West, North and South.

Thus, the well-calibrated policy of official Baku has enabled Azerbaijan to steadily secure its current geopolitical standing — through legal means and without causing harm to secondary or third parties.

Countries that regard themselves, so to speak, as “the centre of the universe” would do well to learn from Azerbaijan — and from the history it is making.