Türkiye–Armenia and the future of regional borders In the wake of Bloomberg’s report

The agreements reached on August 8 in Washington by the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia, in the presence of the U.S. President, not only significantly accelerated the process of normalising Armenian–Azerbaijani relations but also laid the groundwork for resolving Armenian–Turkish relations and, subsequently, reopening the border between the two countries.

In this context, it is particularly noteworthy that informed international outlets see this possibility as realistic. Bloomberg, citing sources familiar with the matter, reports that “Turkey is considering reopening its land border with Armenia in the next six months, according to people familiar with the matter, doing away with Europe’s last closed frontier of the Cold War-era and paving the way to revived trade in the Caucasus.”

It is important to assess the likelihood of this development. Notably, there have been tangible advances in the process of Armenian–Turkish normalisation in recent months. For instance, following the historic Washington meeting, the sixth round of negotiations took place between the special representatives of Türkiye and Armenia—Serdar Kılıç and Ruben Rubinyan—during which the parties reaffirmed the agreements reached in earlier discussions.

However, despite this positive backdrop, talking about opening the Armenian–Turkish border within the next six months would be premature—primarily because full normalisation of relations on the Ankara–Yerevan track is only possible after a final peace is established between Armenia and Azerbaijan. This has been a consistent principle of Türkiye’s political stance, confirmed over time: the border between the two countries has been closed since 1993, precisely at Ankara’s initiative, due to Armenia’s occupation of Azerbaijan’s Kalbajar district.

After the 44-day war, in which Azerbaijan achieved a brilliant victory and liberated its lands from Armenian occupation, Türkiye’s position has remained unchanged: the authorities in Ankara have repeatedly emphasized that Turkish–Armenian normalization is only possible if Yerevan fulfills Baku’s demands within the framework of a peace agenda, the key one being amendments to the Armenian constitution to remove any territorial claims against Azerbaijan.

Thus, Ankara’s stance completely rules out the possibility of opening the Turkish border without establishing a final peace in the region, and such a scenario—even hypothetically—cannot fit within the aforementioned timeframe of “the next six months.” As is known from statements by Armenian authorities, a nationwide referendum on amending the Armenian constitution is scheduled to take place after the parliamentary elections planned for June next year. That is the first point.

The second aspect is that the domestic political arena in Armenia is currently highly turbulent. This is because the Armenian opposition, with some external support, is taking extreme measures to prevent the ruling Civil Contract party from winning the upcoming parliamentary elections. In this context, there are no guarantees that this political event will proceed without complications, even though the current authorities are making every effort to achieve their objectives.

The third point is that there is no complete certainty that the Armenian leadership will demonstrate strong political will regarding amendments to the country’s constitution. This is suggested by the sometimes contradictory statements periodically made in Yerevan. For example, Arman Dilanyan, the President of the Constitutional Court, stated in an interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty that the Basic Law allegedly contains no territorial claims not only against Azerbaijan but also against any other country.

Notably, Dilanyan’s statement came immediately after Prime Minister Pashinyan’s remarks that the new Armenian constitution should not include any reference to the Declaration of Independence, which contains territorial claims against Azerbaijan.

Therefore, considering the combination of the above factors, the idea of opening the Armenian–Turkish border within the next six months appears highly unrealistic and seems more like an attempt to present wishful thinking as reality.

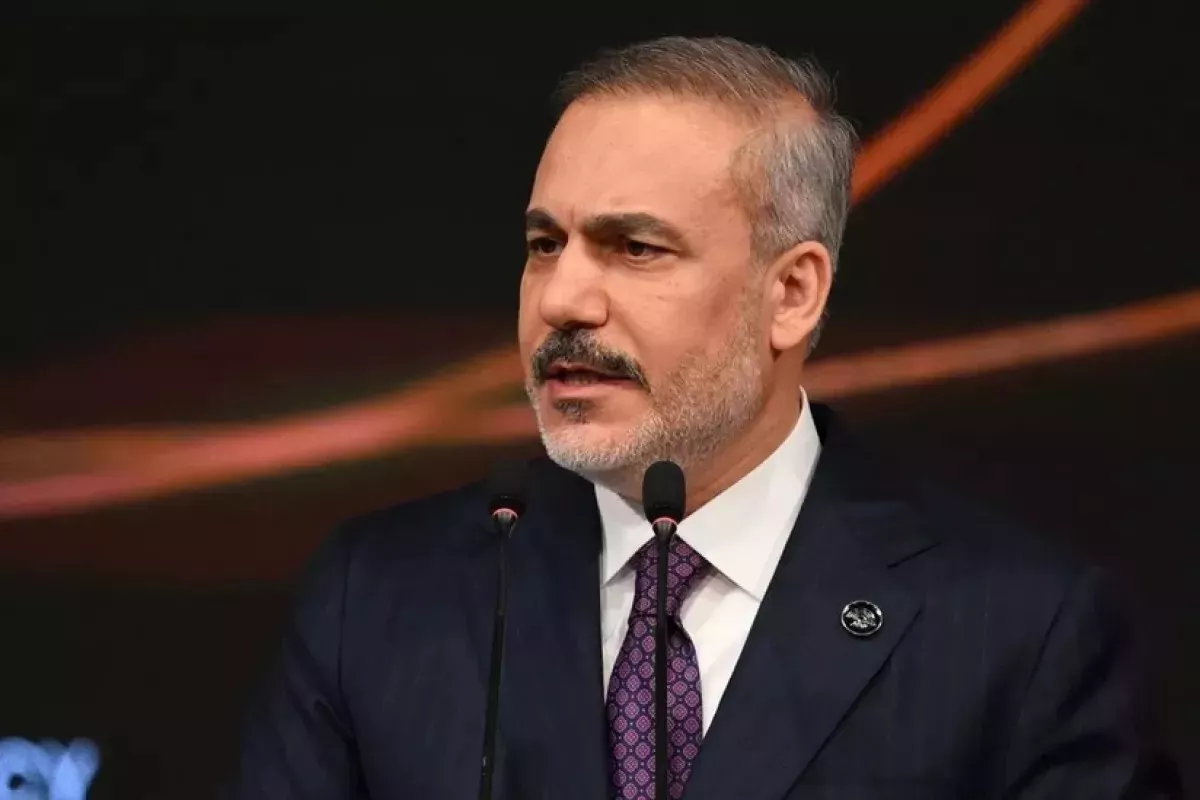

Finally, statements made by Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan at a parliamentary Commission on Planning and Budget provide detailed explanations for why Türkiye has not opened its border with Armenia. First, he noted that Ankara fully understands Yerevan’s motives, as Armenia is interested in restoring economic ties and escaping its foreign policy isolation. Meanwhile, Fidan emphasised that opening the border under conditions of uncertainty would create a situation in which Armenia could delay the process or even avoid signing the agreement altogether, returning the region to a model of permanent political deadlock: “If we normalize relations at this point, we will have taken away the biggest reason for Armenia to sign a peace agreement with Azerbaijan. Therefore, we may face the possibility of a frozen conflict in the region. We don't want this.”

Fidan also reminded that on August 8 in Washington, Azerbaijan and Armenia initialled the text of a peace agreement, but two key issues remain unresolved—the guarantee of unhindered movement through the Zangezur Corridor and amendments to the Armenian constitution, which still contains provisions contradicting the recognition of Azerbaijan’s borders. As the minister assured, “If these issues are resolved, Türkiye will open the border.”

We believe that these remarks by the Turkish foreign minister further confirm the validity of the conclusions we have drawn.