Troubling trends in Armenia mirror pre-war Ukraine

Analyst Conor Gallagher has published an article for Naked Capitalism, saying that there are broad-strokes parallels between the pre-war path of Ukraine and the one Armenia is now on. Caliber.Az reprints the article.

The Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process continues to struggle due to the latter’s insistence on a “corridor” through Armenia and the former’s stance that the West act as a mediator in the talks.

While Azerbaijan wants to start direct negotiations with Armenia, the latter insists on holding them with the involvement of Western governments – something Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev no longer has any interest in. Aliyev recently refused to meet his Armenian counterpart, Nikol Pashinyan, in Granada and Brussels, citing perceived bias against Azerbaijan in the trio format.

Paris is the major issue for Baku, which claims that the process was “hijacked by France”. Azerbaijani officials especially resent France’s sending of weapons to Armenia, which makes it impossible for Paris to be an honest peace broker.

Germany is also reportedly dangling a bunch of money to entice Yerevan to take anti-Russia steps, such as purging the government and armed forces of anyone harboring friendly views towards Moscow. Berlin, already struggling financially, might want to rethink its offer as the tab might get run up quickly considering there might be quite a few Russia-friendly individuals in government considering the two countries’ long history.

“Unfortunately, in Europe there have also been those who have always fueled revanchism and Armenian nationalism,” Deputy Foreign Minister of Italy Edmondo Cirielli admitted recently in an interview with the Italian publication Formiche.

France, which is the home to the largest Armenian diaspora community in Europe, is playing that role at the moment, according to Azerbaijan.

“France is the country that arms Armenia, gives them support, trains their soldiers, and prepares them for another war,” Aliyev told local media in January 2024. If outside parties must be involved, Baku proposes a broader “3+3” framework, involving Russia, Iran, Türkiye, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia.

Zangezur

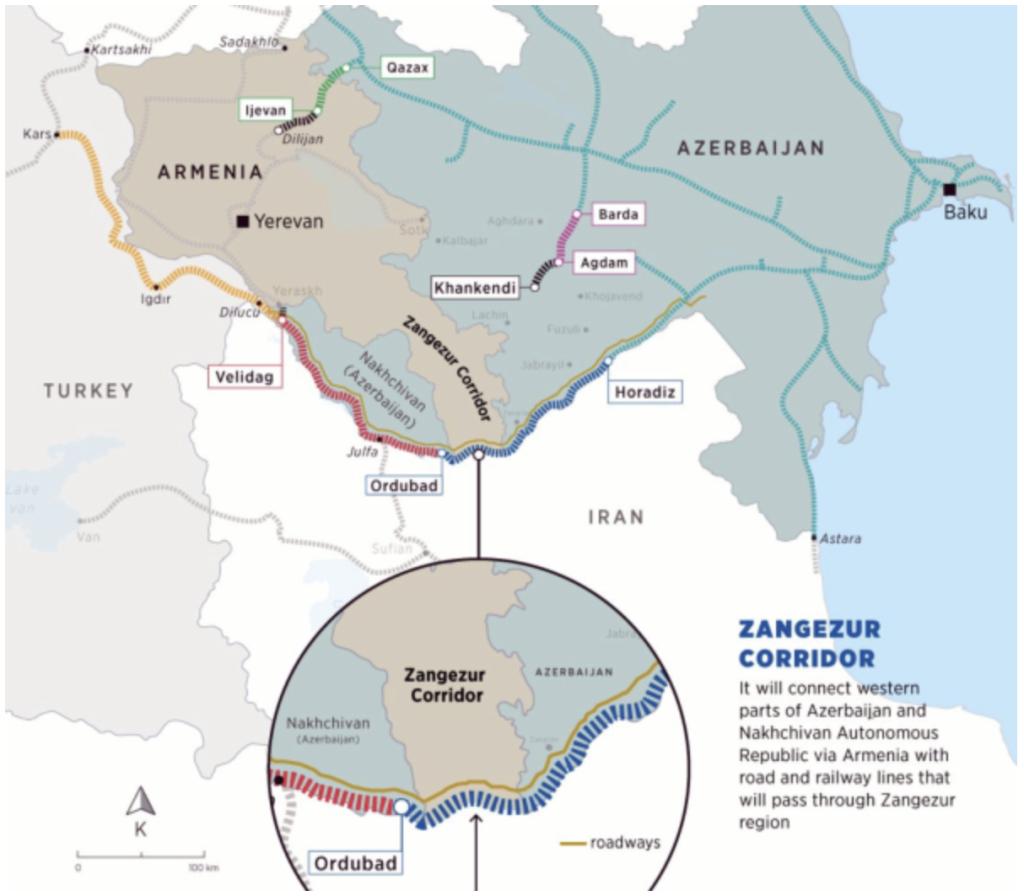

Aside from Armenia insisting on EU involvement, the main roadblock to any deal between Baku and Yerevan remains the Zangezur Corridor – a transportation connection between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave wedged between Armenia, Turkiye, and Iran.

On January 10, Aliyev stated that, if this corridor remains closed, Azerbaijan refuses to open its border with Armenia anywhere else.

The nine-point ceasefire agreement signed under Russian mediation that ended the 2020 war included a stipulation that Armenia is responsible for ensuring the security of transport links between the western regions of Azerbaijan and the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic, facilitating the unhindered movement of citizens, vehicles and cargo in both directions. Azerbaijan and Turkiye have latched onto that point, insisting they have the right to set up transportation links through southern Armenia.

Baku wants travel of people and cargo between Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan to be free of inspection and customs and expects Yerevan to agree to the deployment of Russian border guards along the corridor.

Moscow agrees with the deployment of its border guards, even if it doesn’t see eye to eye on the customs issue (it wants the Russians to conduct the security checks. On January 18, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said the following:

“Armenia is having difficulty opening the route as laid out in the trilateral statement. Yerevan is putting forward additional security requirements for the route. It does not want Russian border guards to be there, though this is written in the statement that bears Pashinyan’s signature. He does not want to see non-aligned customs and border control. He wants Armenia to run it, which contradicts the agreement.”

Lavrov also criticized Western interference, which he faulted for holding up the implementation of the agreements. He’s not wrong.

As the Caucasus sit at the key crossroads of East-West and North-South transportation routes, any alteration to its ecosystem would have far-reaching consequences. Therefore the Armenia-Azerbaijan standoff over Zangezur is drawing in outside actors from near and far, including Iran, India, the EU, Russia, Israel, and of course, Uncle Sam.

Outside actors make peace more elusive?

The situation would be difficult enough to resolve in good times, but with the current breakdown into East-West camps, it’s becoming close to impossible due to outside actors.

Just to recap:

Against the backdrop of the Ukrainian war and the new Cold War, mediating countries began to compete for the status of the main moderator of the Armenia-Azerbaijan negotiations.

Yerevan began to favor the West, and talks mostly moved to Western platforms. It was during those meetings that Armenia agreed to officially recognize Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan.

Once Armenia did so (and PM Pashinyan declared so publicly), the die was cast. The region was (and is) recognized as Azerbaijani territory by the international community but was overwhelmingly populated by ethnic Armenians. Roughly 100,000 of them fled to Armenia after Azerbaijan blockaded the region for months and then moved militarily to assert control in September – an operation that resulted in hundreds of deaths.

Despite moving the negotiation process under the guidance of the West and publicly recognizing Nagorno-Karabakh as Azerbaijani territory, the Pashinyan government has sought to lay all the blame for its loss at the feet of Russia. And Pashinyan now largely refuses to participate in summits with Russia.

Baku, despite assuming control of Nagorno-Karabakh under the guidance of the western process, now wishes to disinvite the West from the process. Why is that?

A range of likely possibilities include some combination of the following:

- The heavy handed involvement of the French who began increasing military support for Armenia last year.

- Baku was being asked to make concessions in other areas, almost certainly having to do with Russia. Azerbaijani officials decided this was not in their interest and/or Moscow applied pressure. (Baku and Moscow share strong ties. In just the energy sector, Russian companies’ large investments in the Azerbaijani oil and gas sector make it one of the bigger beneficiaries of Brussels’ efforts to increase energy imports from Azerbaijan in order to replace Russian supplies. Azerbaijan is also importing more Russian gas itself in order to meet its obligations to Europe.)

- The West was using the process as a way to move Armenia squarely into the Western camp, an outcome that no country in the Caucasus wants.

- It makes zero sense for the West to play such an integral role because its solutions might not take into account (or could actively go against) the interests of other countries with major stakes in the outcome, mainly Iran and Russia.

It would seem that Azerbaijan is refusing to play its role in the West’s attempt to direct the play. For example, when the new US ambassador to Azerbaijan, Mark Libby, was hastily dispatched to the country in December, one of his first actions was to visit the Alley of Martyrs dedicated to those killed by the Soviet Army during Black January 1990. Azerbaijanis weren’t falling for it.

And now the West has reverted to hardball tactics.

France is already upping its military support for Armenia, sending 50 Arquus Bastion armored personnel carriers, Thales-made GM 200 radars, and Mistral 3 air defense systems. There are also discussions to send CAESAR self-propelled howitzers.

The US State Department signaled that it will pause the delivery of all military support to Azerbaijan. USAID, however, is becoming more active in the region, and media campaigns are revving up against the government in Baku. Azerbaijan just ended its engagement with the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe after it began criticizing Azerbaijan’s domestic affairs and made allegations of ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh. Last month, the US put Azerbaijan on its watchlist on religious freedom.

These efforts are likely to prove fruitless as Aliyev has the full support of Türkiye, as well as Russia, and simply doesn’t need the West to get more out of the current situation. And the US, by butting into the process, has helped Azerbaijan and Iran put aside their differences in an effort to keep the Americans out.

Talking peace, preparing for war

While Armenia ups its military spending, getting weapons from France and India, Azerbaijan also remains in preparation mode. Aliyev recently said the following:

“The process of building our army will continue. Armenia should know that no matter how many weapons it buys, no matter how it is supported, any source of threat to us will be immediately destroyed. I am not hiding this, so that tomorrow no one will say that something unexpected has happened.”

Despite the recent boost from Paris, Armenia is still considered to be at a disadvantage. That has long been the story, largely because of its geography. That fact and the long shadow of the Armenian genocide feed into Armenian nationalism that has arguably only worsened the country’s predicament in the post-USSR years.

Some of the more hardcore nationalists founded a group called ASALA (Armenian Secret Army of the Liberation of Armenia) in 1975. Among its goals to force Türkiye to recognize the 1915 events as genocide, pay generous compensations to the Armenian victims and their families, and cede territory to Armenia. To achieve these goals, ASALA killed dozens of Turkish officials in the 70s and 80s. (Türkiye had its own paramilitary forces targeting ANSALA). This more radical strain of Armenian nationalism was also turned against the USSR, including 1977 explosions in Moscow that killed seven people.

Following the USSR collapse, Azerbaijan joined the nationalists’ enemy list and were equated with Turks as the two new countries fought over their border and Nagorno-Karabakh. Although Armenia won control of the territory, it came at a high cost.

Yerevan had no other choice but to fully embrace Russia as security guarantor. The Armenian democratic movement did not view Moscow as a friend, but it needed protectorate status in order to ensure victory.

So Armenia emerged from the conflict with the Nagorno-Karabakh exclave (internationally recognized as Azerbaijan territory), mostly surrounded by enemies, and reliant on Russia for protection (it’s also reliant on Russia economically). This has only served to increase Armenia’s isolation ever since.

Over the past two decades Armenia found itself isolated from the major infrastructural projects in the region, such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Jeyhan oil pipeline, Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline, Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway, as well as many more international initiatives promoted by the Türkiye-Georgia-Azerbaijan triangle.

The same dynamic is at risk of playing out today with emerging transportation links. An absolute nightmare scenario for Armenia is that Azerbaijan and Türkiye open the Zangezur corridor by force, thus excluding Armenia. If Yerevan is banking on the West saving them, they could be disappointed. A more realistic hope is that Iran prevents such a scenario due to its fear of having its connection to the north severed by a Turkish-Azerbaijani line. But if Azerbaijan, Türkiye, Iran, and most critically Russia decide that this is the best path forward, that is what will happen regardless of the West’s objections – and one reason it could happen is Yerevan’s inviting of the West into the region.

It was previously conventional wisdom that the fear of such an outcome and Yerevan’s reliance on Moscow for protection meant it couldn’t turn West, but that was upended last year when PM Pashinyan began to undertake the gambit while still at odds with Azerbaijan and Türkiye.

Pashinyan might be trying to change that, but at what cost?

On January 19, he called for a new constitution, which could eliminate certain hurdles to signing a peace treaty with Baku as the current constitution contains territorial claims against Azerbaijan, as well as Türkiye.

Any such effort is sure to receive significant opposition from more nationalist forces in Armenia already reeling from the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh. Pashinyan has managed to deflect much of the blame for that debacle onto Russia. Would he be successful twice?

Following Ukraine down a dangerous path

There are broad-strokes parallels with the pre-war path of Ukraine and the one Armenia is now on.

Both countries were formerly part of the USSR and maintained strong (albeit complicated) ties with Russia after independence. Both countries experienced a seesawing between the West and Russia. For example, in 2013, the Armenian government was preparing the association agreement with the EU, but at the last moment refused to sign it and instead joined the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (from which Armenia is now slowly exiting).

In both countries, certain factions in the government become convinced that Russia is the source of their problems and/or that they must reorient their country towards the West quickly and at all costs. And maybe most concerningly is the presence in both countries of figures held up in some quarters as national heroes: Stepan Bandera in Ukraine and Garegin Nzhdeh in Armenia.

Both also happened to be Nazi collaborators during World War Two.

Last month, Russia condemned a miniscule march of neo-Nazis that took place in Yerevan on Jan 1.

The gathering was small, but it’s interesting to note that the leader of the group, Hosank, is Hayk Nazaryan, a 34-year-old Armenian-American born and raised in California. He graduated from California State University with a master’s degree in physics and moved to Armenia in 2016. Part of the group’s ideology is that Armenia is being turned into a Russian province, and the only way to prevent it is to become a nation-army.

So one can understand Moscow being wary of such a small gathering, especially in light of how Bandera became a figure certain forces rallied around in Ukraine, and there now looks to be a rise in anti-Russian fascist attitudes from the Balkans to the Caucasus. It’s also not the first time Moscow has criticized Armenia’s celebration of the Nazi collaborator. Back in 2017, the hostess of a program on Russia’s TV Zvezda, a station affiliated with the Ministry of defense, said the following about a statue of Nzhdeh erected in Yerevan:

“The association with the European Union is not the only thing Armenia is doing like Ukraine — it’s difficult to believe, but Yerevan also is valorizing fascist collaborators.”

She also referred to Nzhdeh as “Armenia’s Bandera” and compared the insignia of the ruling Republican Party of Armenia to that of the Nazi Third Reich. You be the judge:

TV Zvezda later apologized. But even current Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan admitted back in 2019 before his turn to the West that the endless veneration of Nzhdeh is part of an effort to drive a wedge between Armenia and Russia.

The date of the neo-Nazi march in Yerevan also happened to take place on the birthday of Nzhdeh. Nowadays, monuments are erected to him, and streets, squares, educational institutions, and strategic centers named after him.

At the risk of being overly brief, here is Nzhdeh’s story:

Over a period of decades, he fought all Armenia’s foes, including Ottoman Türkiye and early Soviet Russia. When World War Two broke out, Nzhdeh threw his lot in with the Third Reich, offering Germany his assistance and providing evidence that the Armenians were an Aryan people. He aligned Armenian fighters with Germany against the Soviet Army and made sure the Armenian legion followed the orders of the Nazis in the Caucasus, Crimea and France. He was arrested by Soviet authorities and died in captivity in 1955.

Does his later collaboration with Nazis tarnish his earlier work fighting for Armenian independence? Not in the eyes of many Armenians. The argument goes that he was a patriot of the Armenian nation who struggled for Armenia’s independence all his life and allied with the Nazis to further that goal.

The thing is, it’s an argument that could be avoided altogether as there are already other Armenian liberation fighters and statesmen who are national heroes, such as General Andranik (who doesn’t come without his own baggage but also didn’t ally himself with Nazi ideology).

It’s not a perfect comparison, but would it be all that dissimilar to France nowadays erecting monuments to Marshal Philippe Pétain who was a national hero of WWI only to head the Vichy puppet government, put in place by the Nazis during the sequel? (The last Rue Pétain disappeared in 2011.)

The danger for Armenia now, following the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh, which is viewed domestically as a humiliating defeat to Azerbaijan, and the subsequent blame being placed on Russia for that loss, is that this ideology of anti-Russian and Nzhdeh veneration spirals out of control. As Armenian-American historian Ronald Grigor Suny said back in 2017:

All post-Soviet countries are rewriting their history at the moment. Those who were heroes are now enemies; former enemies, even fascists, are now heroes. This is happening in the Baltics, and in Armenia. Some people who collaborated with the Nazis, such as Garegin Nzhdeh, are now considered heroes. And the people who murdered Jews in Latvia and Lithuania are no longer denounced, as they were during the communist era. So this is a complicated topic, and historians must work independently of the state and the government to create real histories, not national mythology.

In many ways, it’s fitting that Nzhdeh is playing a role from the grave in today’s brewing conflict. He is credited in Armenia for his efforts in securing Zangezur by leading rebels against Turks and Soviets in 1920.

A little more than a century later, and the situation is essentially back at the start. Armenia, especially the southern part of the country, is at the center of international competition. EU, Russian, and US flags are flying, Iran opened a consulate there last year, and the French are considering doing the same. The names might have changed, but the geography remains the same: it is the most important route through the Caucasus in all directions.