When the past drags you down Can Pashinyan swim toward peace?

The talks between Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan on July 10 took place without pomp or grand statements. While many details of this strictly businesslike meeting remain unknown, the actions of the Armenian government and the reaction from extremist circles in Armenia suggest that it was successful and that the peace process is moving forward.

This progress is aided by the international climate and Baku’s firm policy. Meanwhile, Pashinyan is simultaneously attempting to build his political future by transforming the failed imperial-nationalist project of Armenian hardliners. Riding the wave of normalisation with neighbouring countries, he is cracking down on the opposition.

Progress on several sensitive issues

Revanchist circles in Armenia watched last week’s meeting in the UAE with dread. Metakse Hakobyan, a well-known activist from the ranks of Karabakh separatists, ominously predicted on social media: “The end is near. It’s quite possible he [Pashinyan] will return with a piece of paper labelled ‘peace’.”

Indeed, the draft peace agreement had already been coordinated by both sides earlier in the spring.

Even the word peace is anathema to Armenian nationalists. While a peace treaty has not yet been signed, the two sides are making headway on several issues — including Armenia’s renunciation of territorial claims against Azerbaijan and the restoration of transport links in the South Caucasus.

The Armenian Foreign Ministry spokesperson called the Abu Dhabi meeting “a serious basis for the further implementation of the peace process,” adhering not only to diplomatic etiquette. In recent days, we've heard news concerning key problematic areas.

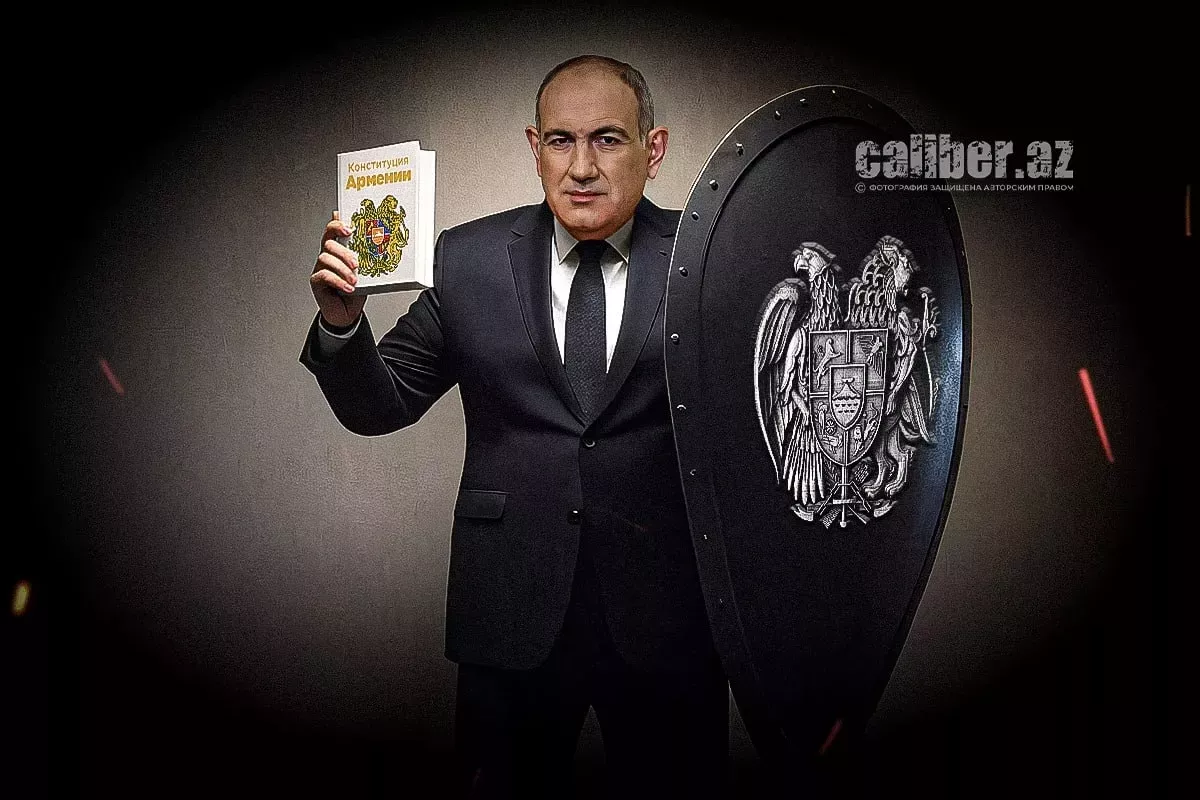

Let’s start with the issue of Armenia’s territorial claims against Azerbaijan. When addressing this, the media usually mention only the tip of the iceberg, avoiding the most complex aspects. One of those visible tips, for example, is the reference in Armenia’s Constitution to the Declaration of Independence, which itself cites a parliamentary resolution calling for the annexation of Azerbaijan’s Karabakh region.

No matter how often Pashinyan insists that this constitutional clause is insignificant and can be neutralised through reservations in the peace treaty, it is clear that this is a ticking time bomb — one that revanchists will eventually attempt to detonate.

And the first victim, incidentally, would be Pashinyan himself, whom they would likely imprison for “violating” that very clause and for seeking reconciliation with Armenia’s neighbours. Which is why, even as he publicly sparred with Baku, deep down Pashinyan knew Aliyev was right. Back in January last year, the Armenian leader agreed that the country needed a new constitution — one that would “ensure the state’s viability under new geopolitical conditions.” At the same time, Pashinyan could use this opportunity to rewrite the Constitution in a way that also benefits his own political agenda.

It appears that the Armenian leadership is now genuinely determined to move in that direction. On the 30th anniversary of the current Constitution, Pashinyan declared: “A new constitution is needed — one approved by the people, so that the people consider it their own, their native rule of life in their homeland-state, created by themselves.”

In doing so, he is trying to undermine the narrative of the revanchists, who claim he is “surrendering” Armenia, while suggesting that Armenians supposedly long for perpetual war against the entire world.

In addition to the constitutional dilemma, there is also the problem of international structures that Yerevan has built over the past thirty years. For decades, the Armenian side exploited the so-called OSCE Minsk Group to advance its expansionist agenda. Today, this structure is no longer functioning — but it still needs to be formally dissolved to prevent any future attempts by global powers to interfere in the peace process. Yerevan no longer objects to this and is now proposing to simultaneously sign a peace agreement and dismantle the OSCE Minsk Group.

These are weighty — but not the most difficult — issues on the road to a peace treaty.

Fight against dog-eaters and confiscation of circus

What’s much harder is the issue of entrenched political forces within the Armenian establishment that openly support territorial claims. On July 11, the Yerevan-based newspaper Hraparak even claimed that Pashinyan and Aliyev had agreed in Abu Dhabi to confront all such forces, prompting Armenian law enforcement to take active measures against opponents of normalisation with Azerbaijan.

Several members of the ARF Dashnaktsutyun leadership have indeed been arrested in recent days, but Pashinyan’s offensive against extremists began well before his meeting with the Azerbaijani leader. It started with a crackdown on the remnants of the revanchist church-led "Maidan".

By arresting their leaders, the Armenian authorities intend to remove Catholicos of All Armenians Garegin II and his associates from their positions in the Armenian Church. “The House of Jesus Christ is occupied by the Antichrist and a dog-eater,” Pashinyan mocked, adding that any connection between Garegin and Jesus has been severed.

At the same time, Moscow-based businessman Samvel Karapetyan, who financed the revanchist clerics, was arrested. As a result, the government first nationalised the electricity networks in Armenia that he had privatised, and then confiscated the Yerevan Circus, also owned by the diaspora “patriot” Karapetyan, who at home had made a habit of grabbing anything that “was poorly guarded.” Additionally, last week the parliamentary immunity of leaders from the Kocharyan-Dashnak opposition in the Armenian parliament was revoked.

Of course, dispersing the church-led “Maidan” and restoring order with extremists in parliament also served Pashinyan’s own interests. Recently, revanchists have stirred and sought help from Russia — the arrests of Dashnak members came against the backdrop of a visit to Moscow by one of their leaders, Ishkhan Saghatelyan.

This helps explain why this party has recently begun to engage in near-coup activities. Its leader, Hrant Markaryan, recently declared live on air that the 1999 shooting at the Armenian parliament was “the highest act of popular outrage and the ‘holy of holies’ of public protest.” And when Pashinyan’s security forces raided the homes of Dashnak activists and leaders in recent days, they found large quantities of weapons and ammunition.

The same was found among the clerics who organised the “Maidan” — the Armenian official establishment, unrestrained in its language, began to display entire arsenals of weapons, describing them as “the ‘instruments’ of the ‘holy struggle’ of Kocharyan-Dashnak terrorists in cassocks, discovered and seized during searches.”

As we can see, Pashinyan’s position could have become precarious had he delayed. Fighting for his own political and even physical survival, he aligns his interests with the normalisation of relations with Azerbaijan and the restoration of the historically unified South Caucasus region.

Clearly aiming to secure his political future by building a different state model — instead of the nationalist dystopia constructed by his opponents — Pashinyan incorporates into his programme the second major issue in the peace process between Baku and Yerevan.

He signals his readiness to agree to the restoration of communications, in particular those connecting Nakhchivan with the rest of Azerbaijan, understanding that otherwise Armenia will be bypassed and left behind, forever stranded on the sidelines of history.

Immediately after attending the summit in Khankendi, President Erdoğan — who recently met with Pashinyan — noted that although Armenia “initially opposed the Zangezur Corridor,” it is now “taking a more flexible position on participating in economic integration.” On this issue, pressure is coming not only from Baku, but also from Ankara. According to the Turkish leader, the corridor is seen not just as part of a geopolitical strategy but as a geoeconomic revolution: the opening of the Zangezur Corridor will be a strategic milestone for the Middle Corridor. Armenia will not be able to obstruct transport routes between China and Europe — but by cooperating with Baku, it could find its niche within these projects.

Amid the Abu Dhabi negotiations, Armenian Deputy Foreign Minister Mnatsakan Safaryan told the U.S.-funded Radio Liberty that Yerevan was ready to transfer control of the roads involved in unblocking the Zangezur Corridor to some form of international structure. However, Pashinyan’s team quickly scrambled to downplay this, claiming the idea wasn’t new and had been on the table since 2022. There’s just one problem: previous statements only suggested outsourcing customs and border services, not the management or security of the corridor itself. This time, however, the implication was clearly broader.

Why is the peace process advancing now?

The leadership in Yerevan remains largely unchanged from three, five, or even seven years ago. So why is the country now moving toward peace and the reopening of regional transport routes — along with a reluctant revision of its failed imperial-chauvinist project?

The foundation, of course, was laid by the successful actions of the Azerbaijani army in restoring the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan. However, even after its defeat, the Yerevan establishment attempted to stall the peace process and reverse the outcome of the war by internationalising the negotiation format.

But Baku managed to put an end to that. In 2023, the Azerbaijani side insisted on shifting the negotiation process to a format without intermediaries, arguing that both the US and the EU, by favouring Armenia (in reality, exploiting its dependence on them), were having a destructive impact on the peace talks.

Relocating the negotiations away from Western and Russian platforms also contributed positively to reaching agreements. The most recent meeting was a clear example of this, as there are no neutral countries left in Europe—today, the United Arab Emirates has become the “new Switzerland.”

Another important factor was the weakening of nearly all global powers and blocs that had previously flirted with Armenian nationalists. The EU–NATO alliance is on the verge of collapse. Russia is consumed by the war in Ukraine and is merely watching as Pashinyan dismantles its allies in Yerevan. The United States is torn by internal conflict and preoccupied with problems in the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific...

But most crucially, the long-standing, futile hope of Armenian revanchists—Iran—has not only weakened (having effectively lost even Syria and Lebanon’s Hezbollah), but is also currently focused on other issues. Its already limited interest in the Caucasus has significantly diminished.

Influential circles within the Iranian leadership had long hoped to use the Armenians and the Armenian diaspora as a bridge to build ties with the EU (and possibly the US)—but this policy has failed, and Tehran has taken notice. This was made evident by the recent visit of the Iranian president to Khankendi.

The ties between Armenian revanchists and Tehran were exceptionally close. Even the revanchist "Dashnaktsutyun" party in Armenia is led by an Iranian citizen, Hrant Markaryan. He moved to Armenia at a mature age and immediately plunged into radical politics. He almost certainly still holds an Iranian passport, as renouncing Iranian citizenship is not permitted. And it’s not just about the passport—Markarian's interviews available in the media are openly pro-Iranian in tone.

Left without foreign patrons, the Armenian establishment has little choice but to begin seriously negotiating with its neighbours. However, the situation can also be viewed from a different angle: Pashinyan is seeking rapprochement because he hopes to use the peace process as a tool to defeat his domestic opponents.

Major political moves are often driven by more mundane political ambitions. In any case, Azerbaijan now finds itself in a favourable international environment—not only to consolidate the results of liberating territories once occupied by Armenian nationalists, but also to play a pivotal role in building an inclusive, peaceful, and prosperous South Caucasus for all peoples of the region.

There can be no full confidence in the Yerevan establishment's willingness for genuine partnership, given the open revanchist sympathies among Armenia’s leading politicians and their tendency to draw external powers into regional affairs. Yet, at times, the future must be built even with difficult partners—after World War II, the French also had to deal with German politicians who were far from agreeable. But by establishing a solid structural framework, they ultimately achieved results.