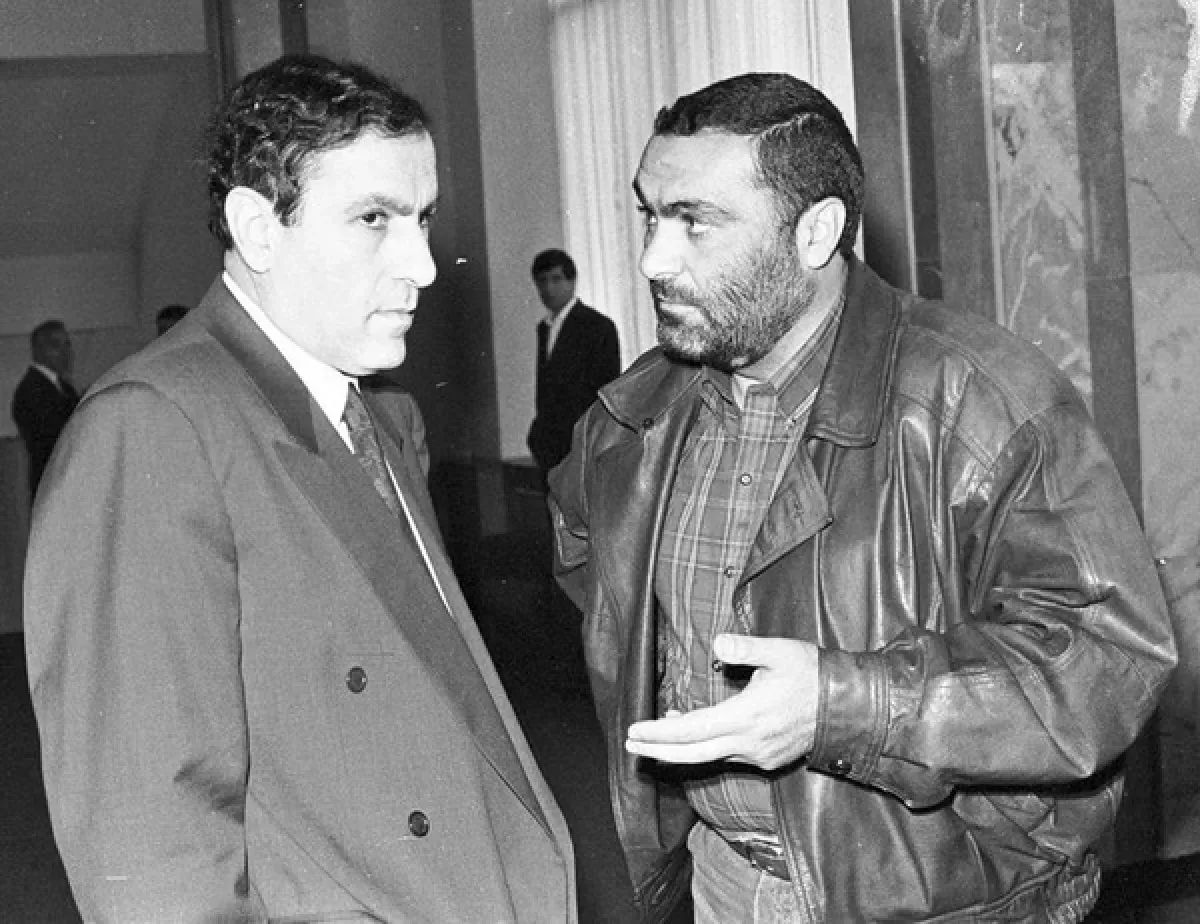

Ter-Petrosyan's new provocations amid Pashinyan’s push for regional peace The ghosts of the past

When studying the history of political battles, one is always struck by the fact that those who once failed spectacularly and brought their countries to the brink of disaster often feel entitled to pontificate about greatness and criticise current governments. This is especially striking when the new authorities are pursuing precisely what their predecessors had systematically dismantled—steering the nation toward a brighter future. Among these perennial critics stands Armenia’s first president, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, who recently remarked, in particular: “The leader of any state, assuming they are not insane, seeks above all to create stability in their country.”

And this comes from a political failure whose personal approval ratings barely rise above the margin of arithmetic error—a fact that, apparently, does not prevent him from presenting himself as a “master of thought.” Upon closer examination of his latest pronouncements, it becomes clear that he has essentially unveiled the political platform of Armenia’s revanchists. Ter-Petrosyan’s speeches contain everything: indiscriminate criticism of Prime Minister Pashinyan, nostalgic references to the early days of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, and exaltation of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

The last point is particularly ironic, given that during Ter-Petrosyan’s presidency, his relationship with the Armenian Apostolic Church was far from ideal. He championed the secular nature of the state, which naturally clashed with the traditional view of the Church playing a leading role in defining Armenian national identity. At the time, Ter-Petrosyan insisted that “Armenia is a secular state, and the Church should not interfere in politics.”

And this comes from a political loser whose personal approval rating hovers around the margin of error—yet that does not stop him from presenting himself as a “master of thought.” A closer look at his recent pronouncements makes it clear that, in essence, he has articulated the political platform of Armenian revanchists. Ter-Petrosyan’s speeches contain everything: indiscriminate criticism of Prime Minister Pashinyan, nostalgia for the early days of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, and exaltation of the Armenian Apostolic Church (AAC).

This is particularly amusing, given that during Ter-Petrosyan’s own presidency, his relationship with the Armenian Apostolic Church was far from ideal. He defended the secular character of the state, which naturally conflicted with the traditional view of the Church’s leading role in defining Armenian national identity. At the time, Ter-Petrosyan insisted that “Armenia is a secular state, and the Church should not interfere in politics.”

One of the most controversial moves during that period was the 1991 law on freedom of conscience and religious organisations, which effectively stripped the Armenian Apostolic Church of its official monopoly and placed it on equal footing with other religions. All of this infuriated the church hierarchy, particularly the then-Catholicos Vazgen I. Therefore, today, in condemning Pashinyan—who, in essence, is also limiting the Church’s attempts to influence Armenian politics—Ter-Petrosyan comes across as strikingly disingenuous.

Ter-Petrosyan claims that Pashinyan allegedly ignores the demands of Armenians who once voluntarily left Azerbaijan’s Karabakh region. “Recently, Nikol Pashinyan has responded to the legitimate demands of over a hundred thousand Karabakh residents, who have sought refuge in Armenia, primarily with reproaches, insults, and sometimes even coarse language. In desperation, these people knock on hundreds of doors, but, finding little response to their requests and demands, they are forced to express their protest through mass demonstrations, sit-ins, rallies, street blockades, and so on,” he stated.

However, Ter-Petrosyan seems to live not in Armenia but in some kingdom of crooked mirrors, where everything appears distorted. In reality, the current Armenian authorities provide Karabakh Armenians with social benefits and housing, and programs are being implemented to employ them.

Another crucial point must be highlighted: Ter-Petrosyan deliberately omits that the policies he pursued in the early 1990s set in motion a chain of events that led to Armenia’s later catastrophes. The outcome was a prolonged military standoff, Armenia’s isolation from regional projects, and the transformation of the republic into a dependent outpost dominated by the Karabakh clan.

It is worth noting that there is video evidence of Ter-Petrosyan’s direct involvement in implementing policies of racial and religious intolerance. For instance, at a meeting with members of the Yerkrapah terrorist organisation in July 1993, he stated: “If it hadn’t all started in 1988, there would be no Karabakh today. We organised the work, formed units, gained experience. Armenia and Artsakh were completely cleansed of other nations.”

Today, this adherent of Nazism—whose presidency saw the occupation of Azerbaijani territories and the perpetration of the Khojaly genocide, and who now associates with Kocharyan and Sargsyan, both of whom are deeply implicated in the bloodshed of the Azerbaijani people—dares to criticize steps taken by Azerbaijan and Armenia aimed at establishing lasting peace between the two countries and the region as a whole. For the first time in many years, the Armenian leadership is taking measures toward peaceful coexistence with its neighbors. This is confirmed both by the support of leading states and by surveys within Armenia itself, where the majority of the population favours peace with Azerbaijan. The path to normalization is undoubtedly difficult, but it represents the only real alternative to a new catastrophe.

Against this backdrop, Levon Ter-Petrosyan’s statements appear as trivial and pitiful attempts at manipulation and opportunism. They are especially inappropriate—and even laughable—given the beginning of Armenia’s emergence from self-imposed isolation and its efforts to normalise relations with Azerbaijan and Türkiye. This is precisely what the international community and the citizens of Armenia demand today: an end to the era of ghosts from the past who embody war, chaos, and poverty.