Fuzuli: Where poetry and progress meet A city reborn from the ashes

The fate of cities is just as intricate as that of an individual—or even an entire nation. In fact, the destinies of cities are often intertwined with the destiny of a people. Once, this place was a small village called Garabulag, but in 1827 it was renamed Karyagin, in honour of Colonel Pavel Karyagin, who made his mark during the war between the Russian Empire and the Qajar dynasty.

For the first time, historical justice was restored on April 2, 1959, when Karyagin was renamed in honour of Azerbaijan’s remarkable poet, Fuzuli. A perceptive and insightful literary critic once aptly called Fuzuli "the true precursor of the decadents." His work is tinged with melancholy, but it's a kind of melancholy that brings a pleasant sadness, one that has nothing to do with despair. There’s not a trace of gloominess in it; instead, it's the sadness that comes with the realization that writing like Fuzuli once did may never be possible again.

His poetry paired with mugham (classical music) —or perhaps mugham paired with his poetry—is something truly mesmerizing. Especially in Karabakh, Fuzuli's verses accompanied by mugham sound particularly unique. Fuzuli belongs to that rare class of poets whose works aren’t just meant to be read—reading them is not enough, it's simply too little. His poems are best spoken aloud, even with your eyes half-closed. And why half-closed, you ask? Let me explain.

The language Fuzuli wrote in is complex—it’s the 16th century, after all—filled with religious and Sufi terms, images, and allegories that one must truly understand. So, why close your eyes? Because if you truly love his poetry, by closing your eyes and reciting his verses aloud, you’ll feel the meaning as he intended it five hundred years ago. You’ll not only understand it with your mind but feel it in your skin and your heart. Some call this an "intuitive immersion," and that’s fine, let it be called that. But I want to emphasize once again: both mugham and his poetry sounded in the city named after him in a way that was truly special. This isn’t just a subjective opinion; it’s exactly what I described above—a deep feeling and intuitive immersion, amplified by the fact that our city once again belongs to us. And where better than in Fuzuli for Fuzuli’s poetry to be heard? Yet, if I may offer a counterpoint to myself: his verses belong everywhere. Across all of Azerbaijan. Our poetry, our mugham, on our land, for our people and our friends.

The City Day was organized at a very high level, and special thanks go to the Ministry of Culture of Azerbaijan for that. And once again, Fuzuli’s poetry with mugham—or mugham with Fuzuli’s poetry—set against the backdrop of Karabakh, under the open sky, sounded simply mesmerizing.

As Aynur Karimova, Head of the Public Relations and Media Department of the Ministry of Culture, aptly noted—and allow me to quote her words: "Fuzuli City Day is being celebrated for the second year in a row, and it has already become a tradition. Celebrating the liberation days of our cities symbolizes both their continued development and the new face of cities that were once almost wiped off the map by the occupiers. They will undoubtedly become even more beautiful because it is our duty to our cultural heritage and to those who spared neither effort nor their lives for their liberation.

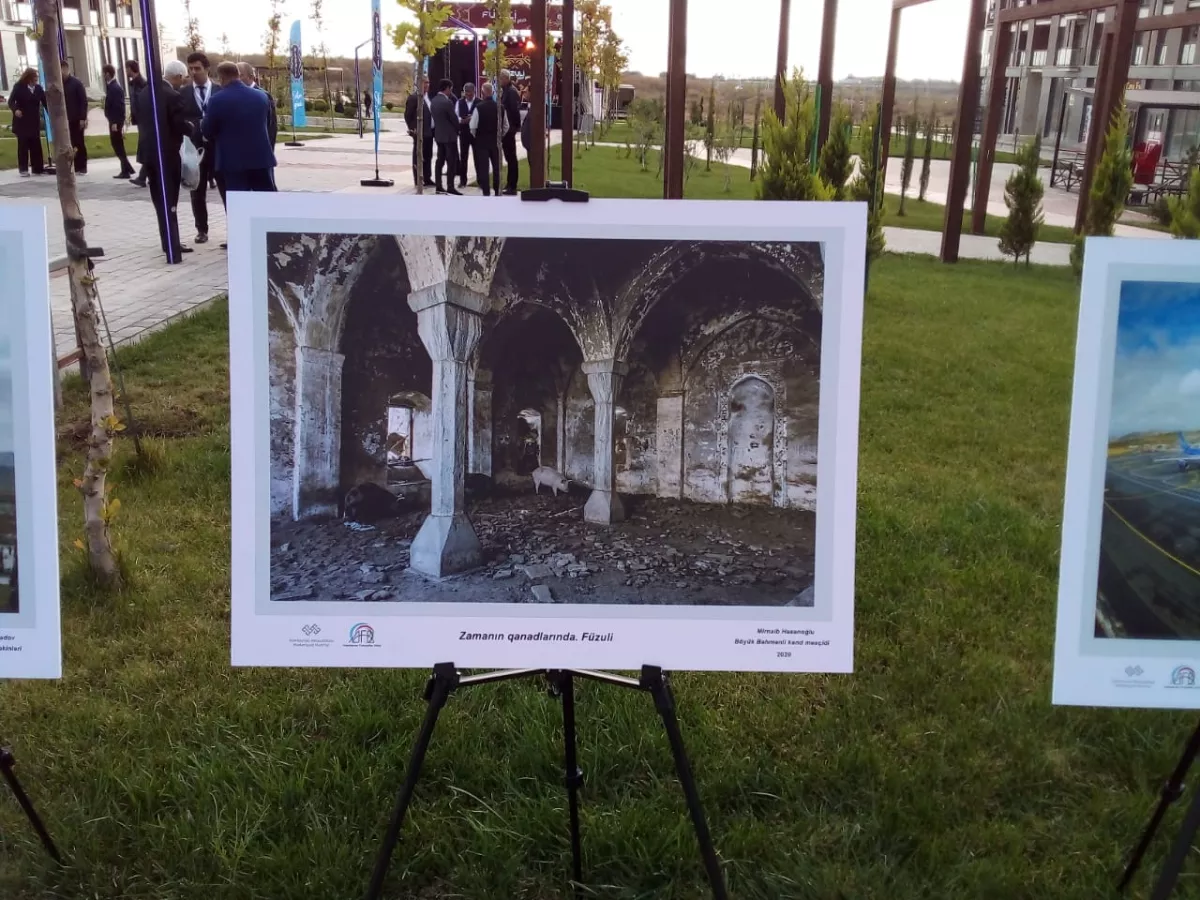

This year, the Ministry of Culture of Azerbaijan has prepared a special program for the residents of Fuzuli as a gift for their City Day, which includes a gala concert featuring performances mainly by natives of Fuzuli. I would also like to draw special attention to the exhibition Füzuli: On the Wings of Time, where we are transported back to the past of this remarkable city, vividly contrasting its state under occupation with the current restoration efforts and what has already been achieved. I hope this celebration will be enjoyed by both the residents of Fuzuli and their children, who will live here and, in the future, make their hometown even more beautiful."

Moreover, Fuzuli is the birthplace of a literary classic, our remarkable writer Ilyas Efendiyev, the author of the brilliant play In the Crystal Palace, which I personally consider one of the pinnacles of Azerbaijani drama, and the novel The Kyzyl Bridge, which, again, I find particularly captivating. Fuzuli and Ilyas Efendiyev—just these names alone would have been enough to make the occupiers tremble, realize they had bitten off more than they could chew, and leave the city quietly "before it all began." But they were stubborn, defiant, and even dared to call Fuzuli some "Varanda." And I’m not joking in the slightest here. That’s why, on October 17, 2020, we had to tear that "Varanda" into shreds. You can wave your "Varanda" in Los Angeles, or Marseille, or Krasnodar—until you're asked to pack up and leave those places, too. And something tells me that next time, they won’t be allowed to take anything with them.

Back in 1993, the occupiers turned Fuzuli into a ghost town, destroying everything they could lay their crooked hands on and displacing over 17,000 people—civilians, in case anyone needs reminding. That same year, in 1993, the UN Security Council passed a resolution demanding that Armenian occupying forces immediately withdraw from the captured city. But they just laughed, not only calling Fuzuli "Varanda" but also claiming it as part of their so-called "security belt." It all ended with that belt unbuckled, "Varanda" in ruins, and a lot of whining about "ethnic cleansing"—whining that even their own backers didn’t believe. Let this be a lesson: don’t mess around with "miatsum" (unification)—medieval doctors believed it could dry out your spinal cord.

There were some striking photographs displayed at the Fuzuli: On the Wings of Time exhibition. For instance, images of pigs inside the ruined mosque in Fuzuli, alongside photos of those who, on October 17, 2020, sent those pigs scurrying away. And they didn’t just run—they squealed about international law, the very law they had been trampling underfoot for thirty long years with their snorts of disregard.

"The restoration of Karabakh and East Zangezur is, of course, an important task for all of us. If I start to list the things we have done since the Second Karabakh War, I will have to speak in front of you for several hours. I would just like to bring a few figures to your and the public's attention. After the war, the amount to be spent by the end of this year is 19 billion manats. Most of the funds is channelled into infrastructure projects. At the same time, efforts are being made to return former IDPs to their homes, and more than 8,000 former IDPs have already resettled in Karabakh and East Zangezur. Their number will increase every month and every year." This quote is from the president's speech at the Milli Majlis meeting held at the end of September this year. Thus, the restoration of the territories that have been liberated for good, including Fuzuli, is progressing rapidly. True owners will not live in the conditions once endured by the occupiers. In fact, true owners wouldn’t even keep their livestock under such conditions, primarily out of respect for themselves.

Restoring what has been destroyed always requires significant funding, and the projects involved are substantial—dare I say, large-scale. And ahead lie even more serious projects. However, companies from countries with pronounced anti-Azerbaijani positions will not be allowed to participate in these contracts. Furthermore, only companies from friendly nations will be permitted to engage in these projects. For example, neither France, Belgium, nor the Netherlands qualifies as friendly nations, which is why their companies will have to stand aside, sulking and eyeing the profits they will never see, under any circumstances. This is both good and right.

We must focus on this financial aspect, as everything else is, for the most part, less significant. Friends should be valued, while enemies should be assessed no more than that. So let’s wish French, Belgian, and Dutch companies luck in seeking profitable projects elsewhere, perhaps in Armenia—if they can find any there, of course. And let’s remember once and for all that in nine out of ten cases, the correct answer to all questions is money. It is also the most effective form of punishment, clear and remarkably impactful.

As of today, 822 families are already residing in Fuzuli. The city is being developed and beautified, and it will undoubtedly become more beautiful than it ever was. This is our city— the city of the poet, the city of the writer, and a place where mugham resonates under the open sky.