Iran's nuclear program and US pressure Deal or war?

U.S. President Donald Trump stated that he sent a message to Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, expressing his desire to reach a new nuclear deal with Iran. The deal would involve Iran abandoning its attempts to develop nuclear weapons in exchange for the lifting of U.S. sanctions, allowing Iran to sell oil and receive Western investments and technology.

Currently, Tehran is on the verge of developing nuclear weapons, and it is likely that it would take no more than six months to achieve this breakthrough. However, it is unclear whether Iran is ready to make such a move. Nevertheless, within the circle of the Supreme Leader, there are loud voices supporting this decision.

Earlier, Trump stated that he would not allow Iran to acquire nuclear weapons. Israel, a U.S. ally and Iran's main adversary, made similar statements. According to senior officials in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's circle, rapid preparations are underway for airstrikes on Iran's nuclear industry. The U.S. has provided Israel with the necessary weapons worth billions of dollars, and now they are just waiting for the green light from Washington. However, the U.S. has not yet granted permission for strikes. They still hope to draw Iran into negotiations for a deal.

The previous nuclear deal was signed in 2015 with U.S. President Barack Obama. This led to the growth of Iran's economy, but in 2017, after Trump became president, he pulled out of the deal and imposed new sanctions on Iran. At that time, Trump’s close friend, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, claimed to have evidence that Iran was violating the terms of the deal. However, apart from him and Trump, no one else agreed with this argument. European countries that participated in the deal did not find Israel’s claims convincing, but they were unable to influence Trump's decision.

Since then, Iranians have lived under sanctions that have had a serious negative impact on the economy. Meanwhile, the country's government went beyond the terms of the agreement a year after the Americans did, starting to enrich uranium to levels close to weapons-grade. In addition, the development of ballistic and cruise missiles – potential carriers of nuclear weapons – was in full swing.

Democratic President Joe Biden's administration attempted to restore the nuclear deal. From 2021 to 2024, negotiations were held with Iran on this issue. In an effort to placate Iran, the U.S., while officially not lifting sanctions, allowed Tehran to increase its oil exports to China. As a result, Iranian oil supplies to Beijing grew from several hundred thousand barrels to nearly 2 million barrels per day.

But Iran did not agree to a new deal. One of the reasons was Trump's decision to pull the U.S. out of the deal in 2017. Tehran felt there was no point in a new deal since the U.S. had not fulfilled its commitments and could withdraw from any agreement at any time.

There was another reason. In the 2000s, the regime of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who had abandoned attempts to develop nuclear weapons, enjoyed Western investments, exported oil to Europe, and seemed to have solved its problems. The West promised Gaddafi the lifting of sanctions and the cessation of strikes against him. However, when a rebellion broke out in Libya in 2011, NATO aircraft intervened, began destroying the regime's bases and columns, and helped the rebels achieve victory.

The ruling circles in Iran are most concerned about a scenario similar to Libya’s, especially since the country has been rocked by strikes and mass protests since 2017. And while in 2015 there were arguments among the country's leadership that managed to convince the Supreme Leader to sign the nuclear deal with the U.S., today those arguments are much less convincing. Nuclear weapons remain a serious deterrent, but on the other hand, what are the promises of the Americans worth?

Today, uncertainty reigns in Iran. Khamenei has made several contradictory statements about the possibility of negotiations with the U.S. From these statements, anything could follow.

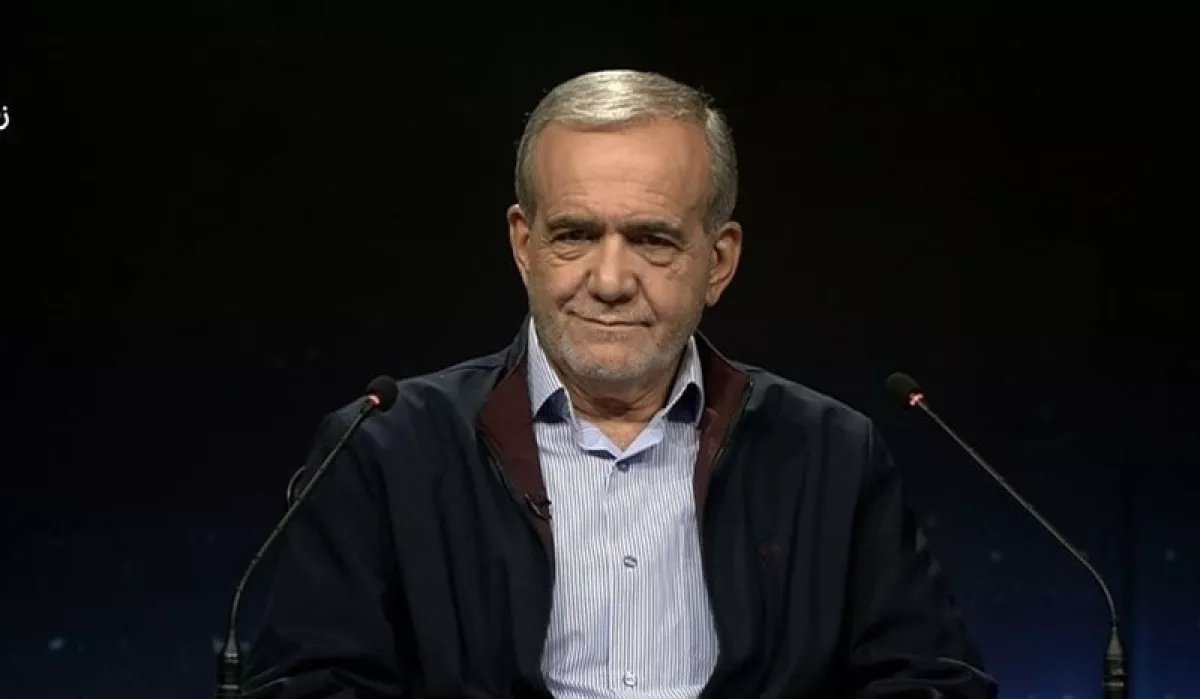

This has led President Masoud Pezeshkian, who belongs to the reformist, somewhat pro-Western or liberal faction of the regime, to call for the start of negotiations. However, the elected president of Iran is little more than a weak prime minister, serving the logistics for the Supreme Leader (as former President Khatami noted).

The powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Iran's second army, which selects the most religious soldiers and officers, not only controls most of the security forces but also half of the economy. It holds real power. As some say, Supreme Leader Khamenei outsourced Iran to the IRGC in exchange for ensuring his personal control over the country. The IRGC pursues a hardline anti-Western stance and strongly opposes negotiations.

However, not all is lost for the reformists. Their influence is based on the support of a significant portion of the population in the capital, as well as the sympathies of regions populated by Azerbaijanis and Kurds. Pezeshkian is linked to Azerbaijani and Kurdish regional lobbyists, and he himself speaks Persian with a strong Azerbaijani accent. In the eyes of the Supreme Leader, Pezeshkian is essential for maintaining at least some legitimacy for the regime, in a situation where the country is shaken by powerful working-class strikes and protests from national minorities.

Pezeshkian, who, unlike Khamenei, is somewhat in tune with public sentiment, having recently been elected to his position, understands that without economic improvements, the country faces major uprisings. He is ready to negotiate with Washington.

It seems that the Supreme Leader, chosen by the regime’s elite 36 years ago, is listening, to some extent, to both the IRGC's arguments and Pezeshkian's words. The final decision on whether or not to engage in negotiations with the Americans will be made by him.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is considering a plan to disrupt Iranian oil supplies by intercepting ships at sea. These measures are aimed at reducing Iran's oil exports to zero and pressuring Iran into negotiations.

Such negotiations may still take place. For example, Tehran might engage in them in an attempt to buy time. However, the chances of a positive outcome are slim.

And it’s not just due to the arguments mentioned earlier. Donald Trump has outlined his demands to Iran. He wants not only Iran's abandonment of nuclear weapons but also the cessation of work on ballistic and cruise missiles. Finally, Trump demands that Iran stop funding and supporting its influential allies in the region, whether it be Hezbollah in Lebanon or the Houthi rebels in Yemen. These demands amount to a de facto rejection of all key tools of Iran's foreign policy. It is highly doubtful that Iran will agree to this, especially in a situation where the U.S. could backtrack at any moment.