Crisis after crisis: Roots of Russia’s troubles with its neighbours Imperial hangover

These days, Moscow likes to quote Tsar Alexander III, claiming that Russia’s only allies are its army and navy. This phrase is used to justify current issues with allies and to hint at the supposed necessity of an unapologetically imperialist policy. The absurdity of this stance is self-evident — made even more amusing by the fact that the Tsar never actually said it. The story symbolically reflects the incompetence and arrogance of Russian officials, which have led to the country's strained relations not only with the West but also with numerous non-Western states. At the core of these problems lies an unwillingness to build equal and respectful relations with other countries.

Wisdom of tsars kaisers: When you have power, who needs brains

As with much of the modern historical revisionism practiced by Russian officials, the case of the fabricated Alexander III quote — which has even been engraved on a new monument to the emperor — is deeply symbolic. In reality, it was not the Russian tsar but the German Kaiser Wilhelm II who used this phrase, and it was later falsely attributed to Alexander III by Russian monarchists. The true author of the quote is best known for having squandered a dynamic empire that had been on a path toward global leadership.

In fact, all successful world powers have thrived precisely because of alliances and coalitions — the entire post-World War II history of the United States is proof of that. Conversely, the collapse of even the largest states has often begun with contempt for allies — the Soviet Union being a case in point, its decline beginning with Khrushchev’s arrogant treatment of China. Modern Russia has failed to learn this lesson. After 1991, it had ideal conditions for building integration blocs and partnerships with many of the former Soviet republics, old Soviet allies, and neighbouring countries linked to the USSR. There were existing diasporas, economic ties, preliminary joint projects, and already established common ground.

Yet, as we can see, three decades on, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) has become a fiction, while the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) are slowly disintegrating as their member states drift toward China’s integration initiatives. Who can be considered a close ally of Russia today? Perhaps Belarus? But even that alliance only solidified once the EU and NATO effectively sealed off Belarus by land and air, leaving Russia as its only outlet.

A telling sign of the systemic flaws in Russian foreign policy is the recurring pattern of Russian officials managing to fall out with countries that are themselves rivals. The current simultaneous deterioration of relations with both Azerbaijan and Armenia is one such example.

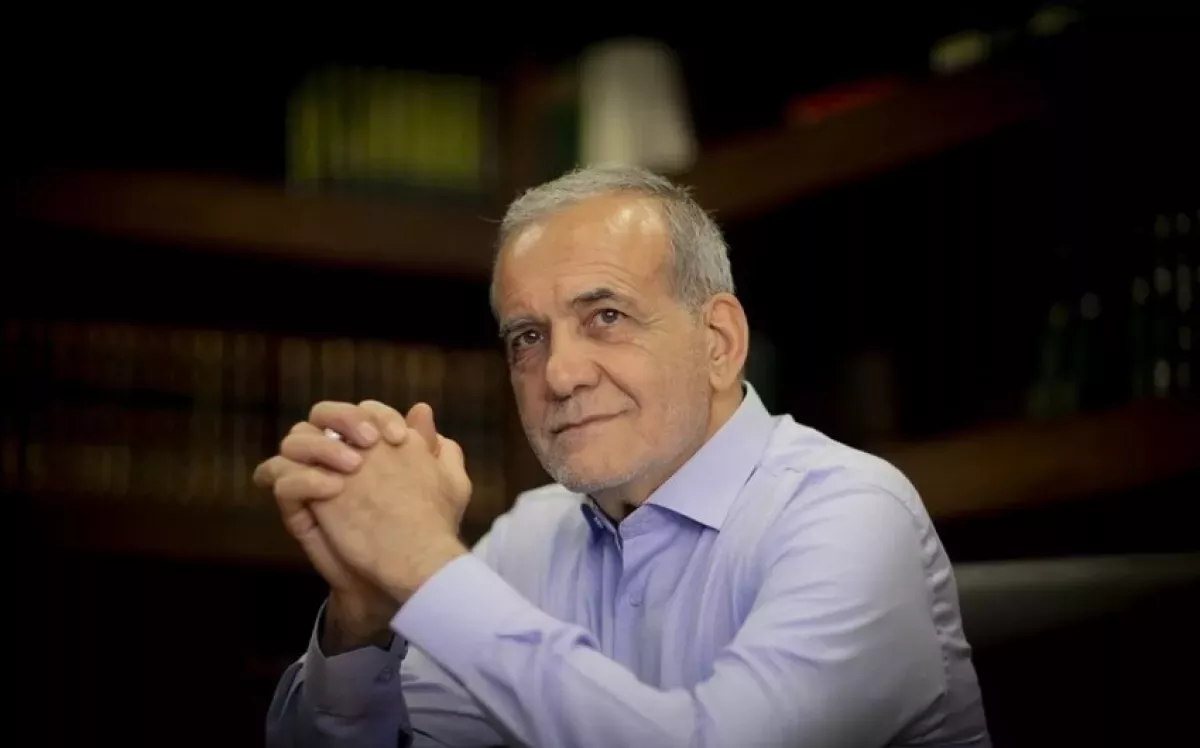

Just recently, Russia found itself at an impasse in its backchannel negotiations with the United States — while at the same time damaging its ties with their opponent, Iran, which Moscow considers a strategic ally. Last week, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian chose not to attend an event of the EAEU — one of Moscow’s key integration blocs. Organisers claimed he couldn’t leave the country at a critical moment. And yet, Iran’s Defence Minister Aziz Nasirzadeh took part in a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation meeting in Beijing, and on July 4, Pezeshkian travelled to Azerbaijan to attend the Economic Cooperation Organization summit in Khankendi. It has now become clear that the Iranian president deliberately snubbed the EAEU gathering. Tehran is displeased with the behaviour of its “strategic partner” during the recent war and with the delays in arms-related agreements.

In other words, Russian policy isn’t even “divide and rule” — it’s outright disdain for non-Western countries, combined with a reliance on brute force and threats. Does it work? Ukraine offers a telling answer. For years, Russians have insisted that Ukraine “doesn’t exist,” that it was “invented by the Bolsheviks.” This absurd narrative has led Russia into a strategic dead end. No matter how often Russian officials boast about breaking through Ukraine’s defences or capturing strategically “important” villages and rural roads, these are costly and largely insignificant moves in the broader context. Despite mounting supply shortages and a depleting pool of manpower, the Ukrainian front still holds.

As Finnish President Alexander Stubb recently pointed out: “This year, Russia has only taken control of 0.25% more territory. Yes, they are advancing, but it is not a major breakthrough. We just need to keep grinding this war and supporting Ukraine.”

Another example: the Baltic states. Russia long ago adopted a strategy of economic strangulation of these so-called “borderland nations” and a show of military force. The result? Today, Russian citizens can only travel to Kaliningrad through Lithuania with biometric international passports — and with anxiety about potential trouble at Lithuanian border checkpoints. Meanwhile, Russia’s Baltic Fleet is now forced to shield civilian vessels from the Estonian Navy.

While there are many minor contributing factors to this state of affairs, they pale in comparison to the central issue: the imperial arrogance and conceit of Russia’s ruling elite. This problem isn’t unique — many great powers have faltered after becoming intoxicated with their own sense of grandeur. What is unique, however, is the Russian elite’s abnormal Eurocentrism and obsession with historical fantasies.

Why negotiate when you believe you can crush?

It was precisely this imperial hubris of the “Russia that rose from its knees” that led, over the past two decades, to the severing of once-close ties with Ukraine. One is reminded of the early 2000s, when Vladimir Solovyov was still a different man and hosted genuinely engaging discussions. Back then, even Kremlin strategist Gleb Pavlovsky, speaking on Solovyov’s show, said some rather insightful things about why Russian policy in Ukraine had failed after the first Maidan uprising in 2004. He said, roughly: “Learn languages — including Ukrainian.

If you believe that Ukraine lies within our strategic sphere of interest, then you must know how to speak to Ukrainians. Do we even have a single official or expert responsible for Ukrainian affairs who can read a book in Ukrainian or address Ukrainians in their own language? What are you hoping to achieve in Ukraine if you refuse to engage with the local context, understand the mentality, and grasp the aspirations of its people?”

In recent years, the attitude toward cultures outside of the “Great Russian” tradition has hardly improved. Just last month, a telling incident occurred during the “Festival of National Literatures” on Red Square in Moscow. Police officers barred even the event’s own participants from entering if they were found carrying books not in Russian. To the police, a non-Russian text was a red flag — potentially extremist or banned. Following a public outcry, access was eventually granted, though only after humiliating searches.

Of course, the issue goes beyond language — and often has nothing to do with it at all. What Pavlovsky was pointing to was a deeper refusal among Russian representatives to take neighbouring partners seriously. Not just formally, but with genuine interest and the willingness to treat them as equals. Nowhere is this failing more evident than in Russia’s relations with countries and peoples that once built the Soviet Union alongside it — or with nearly any non-Western state. Just read what Russian pro-government commentators and military bloggers wrote about Iran during the recent war. Or take note of the racist remarks made by prominent Russian commentators, some closely tied to state institutions, following the Thursday appointment of an ethnic Azerbaijani as dean of a faculty at MGIMO.

Pathological Eurocentrism

This condescension toward “borderland” nations and many non-Western countries within the Russian establishment goes hand-in-hand with a pathological reverence for the West in virtually every domain. Describing a similar syndrome in Shah-era Iran, Jalal Al-e Ahmad coined the term “Westoxification.”

As practice shows, Russia’s elites are prepared to build serious relations in global politics only with partners from Western Europe and its “white” settler offshoots, such as the United States. Only these actors are regarded as truly worthy interlocutors. Meanwhile, like a sleight of hand, the main adversaries in Russian discourse change, but this principle remains constant. Yesterday, the main villain was the U.S., allegedly stoking war in Europe while the continent stood by helplessly, even as Russia claimed to seek an agreement. Today, the narrative has flipped — now it’s supposedly the EU that won’t let Washington end the war, while Russia again claims it's open to negotiation. But whether it’s yesterday or today, Russia’s elites consistently deny agency to all the countries located between it and “the West.” These nations are deemed either incapable of negotiation or simply too insignificant to matter.

The results of this worldview are plainly visible: a hardened wall of hostility now surrounds Russia. First, it emerged along the European frontier. Now, a similar dynamic threatens to unfold along Russia’s southern borders — in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. This cannot be written off as Western intrigue, because Russia is facing the same breakdown of relations with countries that are themselves mutual rivals. That means the root of the problem lies above all in Russia itself.

A love for the bloody “prison of nations”

And here we come to the third factor behind the current catastrophe in Russia’s relations with its neighbours. After the failure to build a “liberal empire” adorned with nanotechnology and other futuristic trappings, the Russian elite retreated into the past. And not just any past — but the darkest years of tsarist imperialism. The consequences for foreign policy are clear. If the model you emulate is the old empire, then chauvinism and violence, racism and authoritarianism, become acceptable tools of statecraft.

After the start of the war with Ukraine, several Russian officials — most notably Alexander Bastrykin, Chairman of the Investigative Committee — began calling for the adoption of a state ideology. When outlining what such an ideology might be built upon, Bastrykin offered a telling list of values: “Love of the past, compassion, faith in God — these are all constitutional values.”

He made it quite clear which version of the past should be cherished, pointing to a specific historical figure — Count Sergey Uvarov, Minister of Education under Nicholas I — and highlighting his famous ideological triad: “Autocracy, Orthodoxy, Nationality.” Basing modern ideology on this minister of Tsarist Russia (under Nicholas the “Stick”) is, to put it mildly, a dubious idea. Even Pushkin mocked Uvarov’s corruption and greed in verse. And the disastrous defeat in the Crimean War — which ultimately forced Russia to withdraw from the American continent — also lies partly at his feet, as he kept the education system in a state of intellectual stagnation.

But Russia’s elites generally know little about the real nature of the Tsarist Empire — and seem to care even less. A monument to Uvarov was recently unveiled. As former U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton aptly observed, the ideology of Russia’s current establishment is essentially “Tsarism”: a politicised nostalgia for the imagined grandeur of the Romanov Empire.

This politicised historical reenactment inevitably leads to conflict with all of Russia’s neighbours. The adherents of this imperial nostalgia are already stoking hostility across both the Caucasus and Central Asia. The Russian Minister of Education speaks of the supposedly “disputed status” of Karabakh, while state-aligned Russian experts have recently lashed out at Kyrgyzstan for including references to colonial oppression and looting under Tsarist rule in its education system. And yet these are indisputable historical facts. Russian chauvinists are insulting a friendly, modern state by dragging the discourse back to the disputes of the Nicholas II (“the Bloody”) era. They did this during a successful state visit by the President of Kyrgyzstan to Moscow — clearly aiming to sabotage high-level negotiations. Could anything be more absurd?

None of this bodes well for the Russian people or for Russia as a country. On the contrary, the future depends on how quickly these problems are recognised — and how swiftly Russia can shed its chauvinism and historical delusions, and build respectful relations with all its neighbours, big and small, Western and Eastern. One way or another, Russia must learn to live in the modern world — a world where diplomacy is required with every state, not a 19th-century world in which the Russian Empire only needed to make deals with a handful of European powers while subjugating the rest through brute force.