Two Iranian perspectives on the South Caucasus Velayati versus the Zangezur Corridor

Advisor to the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ali Akbar Velayati, once again tried to play the role of the “guardian” of the South Caucasus by publishing a sharp statement on the social network X regarding the Zangezur Corridor. In it, using rather aggressive rhetoric, he warned that any attempts to implement the transport connection project between the main territory of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic would meet a “firm response from Iran.”

First, let us remind Velayati that the issue of transport links between the western regions of Azerbaijan and its Autonomous Republic is not someone’s geopolitical fantasy, but a commitment enshrined in an international document — namely, paragraph 9 of the trilateral statement dated November 10, 2020, signed by the leaders of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Russia. Iran was not at this table and, therefore, is not a party with the right to veto the implementation of the provisions of this agreement.

The most interesting aspect of this story is that, unlike Velayati, the Armenian leadership demonstrates a much more constructive and rational approach.

Thus, on the issue of the Zangezur Corridor, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan made a statement confirming that Yerevan had received a proposal from Washington regarding the management of this corridor. According to him, contacts between Armenia and Azerbaijan could help overcome the existing deep mistrust between the two countries. Consequently, the prime minister emphasised the following: the proposal for managing the Zangezur Corridor does not contradict Armenian legislation, which provides for the right to develop infrastructure. As examples of outsourcing, he mentioned Zvartnots Airport, the South Caucasus Railway (SCR), and the water supply system.

Recently, Armenian President Vahagn Khachaturyan also stated: “If we can open the gates of Syunik [Zangezur — editor’s note], I mean the possibilities of the 43 kilometres, then you can be sure that the future will offer us great opportunities for development.”

You must agree that Velayati’s attempts to act as a bigger Armenian than the prime minister and president of Armenia, to say the least, appear inappropriate. Especially since the prospect of a transport corridor between “mainland” Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan does not imply a “land blockade” of the Islamic Republic of Iran, as Velayati claims. None of the proposed route options violate Iranian territory, restrict its trade, or infringe on its national interests. On the contrary, the regional unlocking of transit routes promotes the development of the entire region, including the Islamic Republic itself—if it wishes to participate in this process constructively.

Accordingly, Velayati’s attempt to intervene in matters that concern exclusively Baku and Yerevan appears to be an effort to artificially maintain Iran’s influence in the region, at the cost of losing objectivity and respect for the sovereignty of other states.

Ali Akbar Velayati likely believes he is defending his country’s strategic interests, but his statements resemble rhetoric from the Cold War era. This, by the way, is not surprising given that he served as Iran’s Minister of Foreign Affairs for a long 16 years, from 1981 to 1997. Those were years of the harshest confrontation between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the United States. So perhaps Velayati is simply using the language of communication familiar to him for decades, forgetting that times have changed, the South Caucasus is evolving, and these changes require new approaches.

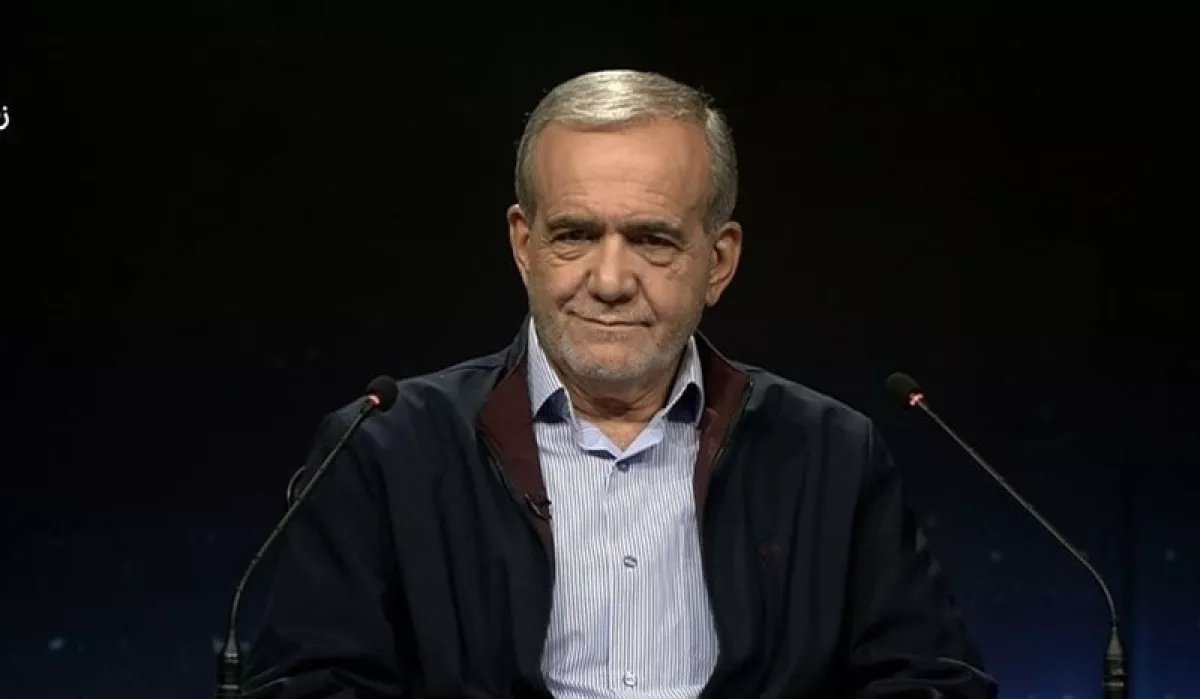

What exactly are these new approaches? Their example was recently demonstrated by the President of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian, who, during his visit to Zanjan, spoke about the need to strengthen ties with the countries of the region, particularly with Azerbaijan. The Iranian president noted that there had previously been various opinions regarding Azerbaijan’s position, but he personally visited the country and considers its people “our own, our close ones.”

“How is it possible that I cannot go there and form an alliance with them, while Israel can? I must ask myself: what is my mistake, why was I unable to establish friendly and healthy relations with my brothers and sisters, while Israel succeeded? The fault is mine, not theirs. They are our brothers and sisters, our own and close ones,” Pezeshkian said.

As the saying goes, may his words be heard by Ali Akbar Velayati.