Iran in turmoil again From stagflation to street unrest

Protests erupted in Iran on December 28, as merchants closed their shops and joined the streets in response to the worsening economic crisis, with the exchange rate for one US dollar reaching 42,000 Iranian rials.

The economic situation had been deteriorating for several months and reached its peak on December 28. The next day, the protests spread widely: merchants staged strikes in several districts of Tehran, after which many city residents joined them. Demonstrations also began in other cities. They have been reported in Ahvaz, Hamadan, Karaj, Qeshm, Zahedan, Mashhad, and Shiraz.

These large-scale protests are cutting across various social strata, classes, and ethnic groups. They are spreading, encompassing small businesses, the working class, civil servants, as well as regions populated by ethnic minorities. According to the latest reports, students from the University of Tehran and transport workers in different regions have joined them. Students from the University of Technology in Tehran, addressing other students, chanted: We don’t want spectators, JOIN US”

The transport workers’ union announced a strike; however, unions in Iran are weak and persecuted by the state, and strikes outside of unions (“wildcat strikes”)—organised through workers’ assemblies—are more common. Such actions can be more dangerous for the regime because they are not controlled by union leadership, which is accustomed to negotiations and compromises.

The protests are becoming politicised. Videos from Iran show crowds chanting slogans against the Islamic Republic, and sometimes in support of the Pahlavi dynasty, shouting, for example, “Pahlavi will return!”

The demonstrations followed the government’s decision to raise the price of subsidised fuel. In Iran, increases in gasoline prices had long been postponed due to fears that they might trigger a repeat of the large-scale protests of November 2019 (the so-called “Bloody November”), which were brutally suppressed by the regime. However, the government announced the price hike starting December 6. Everyone expected riots that day, and the authorities deployed security forces, but nothing happened. Nevertheless, the outbreak of anger apparently did occur, but was postponed due to fear of the security forces. When further bad economic news arrived, the protests finally began.

Iran’s economy is in a state of recession. The World Bank forecasts an economic contraction of 1.7 per cent in 2025 and 2.8 per cent in 2026. This downturn is being compounded by rising inflation: according to Iran’s Statistical Center, monthly inflation in October reached 48.6 per cent, the highest in 40 months. These are official figures, while critics of the regime claim that the real numbers are much higher. Such price increases are pushing the population into poverty.

Iran is experiencing stagflation: GDP is shrinking while inflation is rising. The country is facing perhaps the most difficult economic situation that the government and nation have encountered in recent decades. This crisis is compounded by a water shortage (many Iranian cities lack sufficient water) and a critical state in the energy sector, with authorities occasionally cutting electricity in several regions.

The regime, unable to cope with economic and social problems, is losing stability. The ruling groups consist primarily of members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the country’s second 100,000-strong army, which simultaneously controls the intelligence network and the Basij militia suppressing protests. The IRGC leadership controls many of the country’s major companies, both state-owned and private, as well as a number of key ministries. Unlimited subsidies from the treasury and the habit of appointing relatives everywhere have turned Iranian enterprises into feeding grounds for the enrichment of a narrow ruling elite. This has isolated Iran’s leadership from other social groups: while they enrich themselves, everyone else grows poorer. Corruption, nepotism, and incompetence have become commonplace.

The economic situation is further complicated by sanctions imposed by the United States, European countries, and the UN. These sanctions were introduced because of the Islamic Republic’s attempts to develop nuclear weapons. As a result, Iran has not yet developed nuclear weapons, but its ability to export oil has been sharply reduced. In the past, oil exports accounted for up to 90 per cent of the country’s foreign currency revenues and funded around 40 per cent of social services.

Beyond the economic challenges, a political crisis is brewing. Demonstrators chanted slogans in support of Iran’s exiled crown prince, Reza Pahlavi. There were also calls for the death of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and expressions of anger over his policy of supporting Iranian proxies abroad while Iran’s economy is in dire condition (“Neither Gaza, nor Lebanon, I will sacrifice my life for Iran”).

Security forces began dispersing the protesters, while Reza Pahlavi, who lives in exile, issued a statement saying: “My special message to the security and law enforcement forces: this system is collapsing. Do not stand against the people. Join the people.”

However, it is not only monarchists who are protesting in Iran; there are a variety of sentiments and political views within the country.

The coming days could prove decisive. If the authorities disperse the protesters, a new wave of the movement may emerge in a year or two, as happened after the “Bloody November” of 2019. However, if they do not, the movement could spread across the entire country.

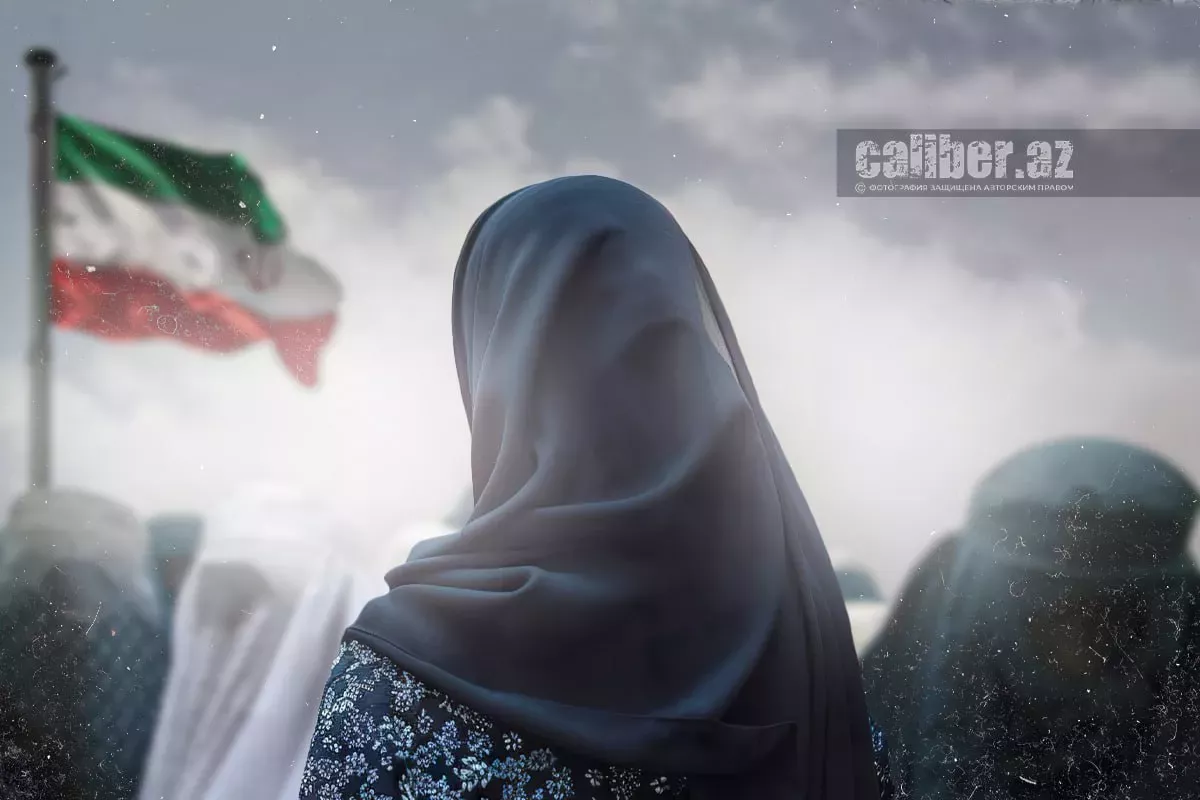

The history of modern Iran increasingly resembles a series of uprisings: the 2009 “Green Revolution” (protests involving millions of Iranians who accused the government of election fraud); working-class uprisings in 2017–2018, during which independent strike committees were formed at some factories under the guidance of workers’ assemblies; the 2019 “Bloody November” (as mentioned above); and the 2022–2023 “Mahsa Amini Uprising” under the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom!”—protests sparked by the killing of a young woman by police for allegedly wearing the hijab “incorrectly.”

However, the situation in Iran today differs from the Mahsa Amini uprising a few years ago. A new and important factor has emerged. If the events in Iran escalate into a large-scale revolt reminiscent of the Arab Spring, and certain regions become cut off from regime forces, there is a high likelihood that Israel may attempt to implement scenarios similar to those in Libya or Syria. This would mean that the Israeli Air Force could begin supporting anti-regime forces with airstrikes, increasing their chances of success.