Tactics without arguments Inside the anti-Azerbaijani campaign

There’s a foolproof sign that a state is on the right track: it’s not compliments or diplomatic niceties—it’s provocations. The stronger Azerbaijan grows, the more nervous and aggressive the attempts to discredit it become. The past few weeks have offered yet another clear confirmation of this.

On February 18, 2026, President Ilham Aliyev, at the invitation of United States President Donald Trump, visited Washington for a working trip to participate in the first meeting of the Board of Peace—a new international platform established on the initiative of the American administration. Leaders and representatives from 27 countries gathered at the Donald Trump Institute of Peace. In his address to the assembly, President Trump specifically highlighted the progress in the Armenian-Azerbaijani settlement, thanking both Aliyev and Pashinyan for their efforts. The context of the visit was entirely positive: Azerbaijan emerged as one of the key partners in the new American diplomatic architecture, and its role was recognised on a platform aspiring to be the main international venue for peace negotiations.

It was precisely at that moment, almost as if on cue, that a provocation was set in motion. Outside the Waldorf Astoria, where the Azerbaijani delegation was staying, a group of aggressively hostile individuals appeared. Their behaviour had nothing to do with the civilised expression of opinion. Instead of slogans, there were shouts and insults; instead of arguments, there was an attempt to break through the security cordon. The incident was aimed at a single goal: to create an image that could be reproduced, distorted, and woven into a predetermined narrative. The President’s Security Service, together with the American police, quickly put an end to the inappropriate behaviour within minutes. But the media machine was already in motion.

What happened next was as predictable as it was revealing. Within just a few hours, publications appeared following the exact same template: the participants of the incident were portrayed as “peaceful protesters,” the security personnel as “aggressors,” and the context of the visit was completely erased. Not a word that the President of Azerbaijan was in Washington at the invitation of the American leader. Not a word about the Board of Peace. Only shouting, “victims,” and accusations. This is a standard playbook, familiar to any analyst acquainted with the logic of information warfare.

At this point, it is important to pause and consider what lies behind such episodes. The incident at the Waldorf Astoria is not an isolated event; it is a fragment of a larger mosaic, a component of a far more extensive and systematic campaign increasingly targeting Azerbaijan. And to understand its nature, it is not enough to analyse each individual episode. One must see the full picture.

Any specialist in information security will tell you that provocation itself is only the visible part of an operation. Far more important is what precedes it and what follows. A classic hybrid pressure scheme looks like this: first, an informational backdrop is created—through leaks, planted stories, and fabricated “investigations.”

Next, this backdrop is amplified through social media, where coordinated groups push the desired narratives, giving them the appearance of widespread public outrage. At the same time, tools of personal discredit are employed—rumours, insinuations, and falsifications targeting the private lives of state leaders. Finally, once the media environment is sufficiently “heated,” the next phase occurs: street actions, incidents at hotels or in front of international conference venues, attempts to create situations that can be captured on camera.

This combination—information injection, emotional radicalisation, street pressure—has long been described in specialised literature and is used as a tool to undermine trust in state institutions, create internal tension, and attempt to delegitimise authorities. Such techniques have been used and continue to be used in the post-Soviet space, in Middle Eastern countries, in Latin America—anywhere certain actors seek to influence the political course of a sovereign state without resorting to open military confrontation.

Let us pay attention to the chronology. The intensification of provocative activity against Azerbaijan consistently coincides with moments of diplomatic success for Baku or major international events. This was the case in August 2025, when Aliyev and Pashinyan signed the Washington Declaration under Trump’s mediation, marking a historic step toward a comprehensive peace treaty. It is happening now, as Azerbaijan is included among the member states of the Board of Peace and demonstrates growing influence in regional and global diplomacy. Every major success of Baku on the international stage is accompanied by a surge of anti-Azerbaijani hysteria. A coincidence? For anyone familiar with the patterns of information warfare, the question is rhetorical.

The northern vector of this pressure deserves particular attention. Throughout 2025, relations between Baku and Moscow went through a series of crises—from the AZAL plane tragedy in December 2024, when Azerbaijan demanded that Russia acknowledge responsibility, to the deaths of Azerbaijani citizens during detention by Russian security forces in Yekaterinburg in summer 2025. Baku’s response was firm and consistent: the closure of Rossotrudnichestvo (Russian House) structures, the suppression of intelligence networks operating under the cover of media and public organisations. Plans to draw Azerbaijan into the so-called “Eurasian movement” were thwarted, and influence levers that had been built over years and disguised as expert and cultural activity were exposed.

The reaction was predictable. Large-scale cyberattacks, coordinated information operations, streams of disinformation on social media, and campaigns aimed at personally discrediting the country’s leadership—this is the usual toolkit. The Russian Federation has repeatedly demonstrated the use of such scenarios across the post-Soviet space. One need only recall the experiences of Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, and the Baltic states—everywhere a state chose a sovereign foreign policy path, it encountered the same matrix of pressure.

But it would be an oversimplification to attribute everything solely to one direction. Azerbaijan faced a synchronised attack from multiple sources. Certain European institutions continue to exert residual pressure, inherited from an era when Baku was pressured to follow rules imposed from outside, under the guise of “human rights” and “democratic values.” French and Swiss channels play a role in shaping the anti-Azerbaijani agenda—not only in the media but also at the level of state institutions, including parliaments. There, it is not uncommon to see assessments where facts are replaced by emotions, and individuals and illegal structures that previously operated in Azerbaijan’s occupied territories are presented in a romanticised light.

A separate mechanism of pressure is built along the American vector—through structures of the Armenian diaspora. Even though Yerevan is officially moving toward a peace treaty with Baku, more than eighty Armenian civil society organisations continue to promote the “Artsakh” agenda—a non-existent quasi-state entity. These structures possess a powerful lobbying infrastructure, are embedded in media and political networks, and serve as a ready-made tool for any external actor interested in destabilising Azerbaijan. When the interests of Armenian revisionism align with those of actors irritated by Baku’s independent course, enduring coalitions emerge, operating in synchrony.

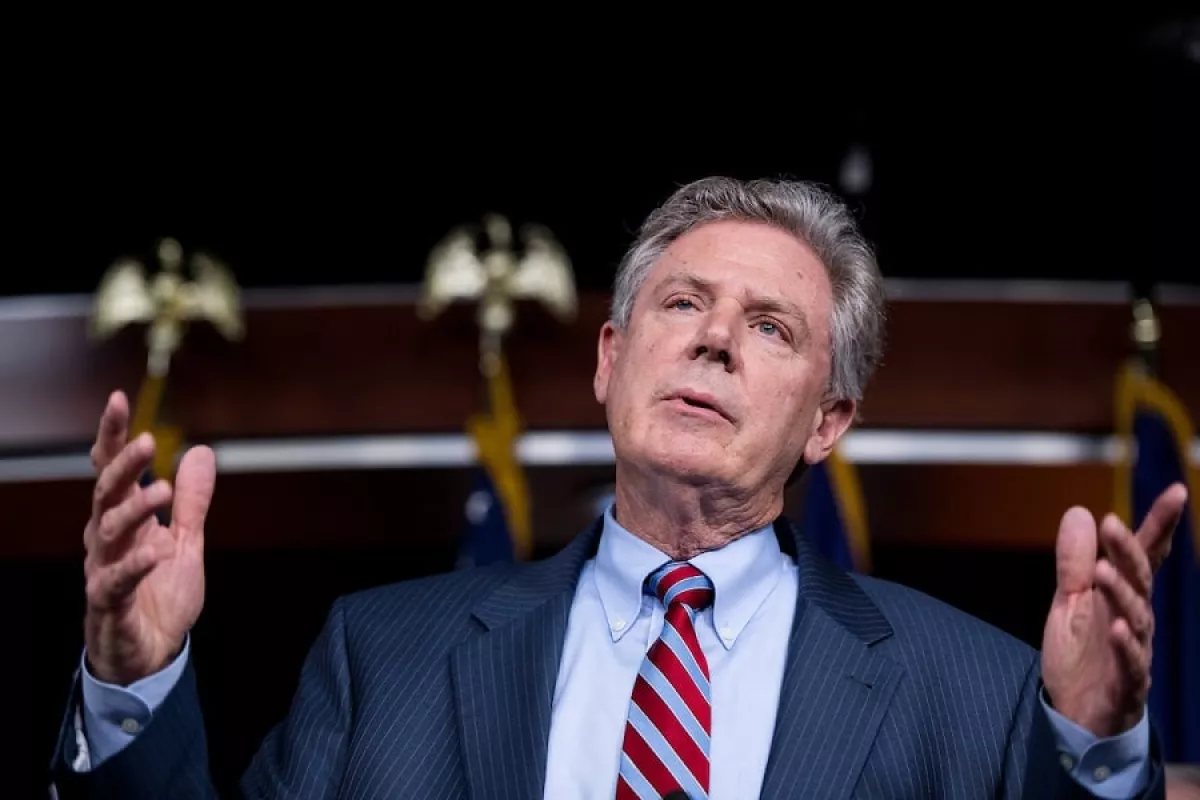

The Washington incident demonstrated this mechanism in a textbook fashion: almost immediately after the provocation at the Waldorf Astoria, the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA)—long active in shaping an anti-Azerbaijani agenda in the United States—publicly supported the aggressive actions. Following in the familiar pattern was Congressman Frank Pallone—a politician whose biography reads like a chronology of anti-Azerbaijani lobbying: denial of the Khojaly tragedy, demonstrative visits to territories formerly under Armenian occupation, and consistent opposition to the restoration of Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Street provocation, immediate media support from lobbying structures, the emergence of controversial politicians onto the forefront—this is a well-rehearsed model, in which marginal “on-the-ground” activity intersects seamlessly with institutional pressure in the political and media spheres.

Yet in Azerbaijan’s case, this scheme systematically fails. The country has passed through a phase in strategic theory known as “institutional maturation.” A state that won the 2020 war, fully restored its territorial integrity in 2023, concluded historic agreements with Armenia under the mediation of a major global power, and integrated into the orbit of key international initiatives, no longer needs external approval. It acts rather than explains. It sets the agenda rather than reacting to someone else’s. It is precisely this shift that generates the greatest irritation among those accustomed to seeing post-Soviet countries as objects rather than actors in international politics.

Russia, which for decades built mechanisms of control over the South Caucasus, has lost most of these levers. The peacekeeping contingent in Karabakh, intended as a tool of strategic presence, has been withdrawn. Intelligence networks operating under the cover of media structures have been exposed and neutralised. Attempts to exploit ethnic divisions yielded no results. Energy pressure through sabotage against SOCAR infrastructure—including the strike on the oil depot in Odesa in August 2025—also failed to produce a strategic breakthrough. Azerbaijan methodically closed one loophole after another through which external forces attempted to penetrate the internal space of the state.

It is precisely in this context that the current wave of anti-Azerbaijani provocations should be understood. These are rearguard actions. They are the moves of those who have lost the strategic game and now seek to create an illusion of activity through tactical strikes. In military terminology, this is called “harassing fire”—it cannot change the course of the battle, but it can temporarily divert attention from what is truly decisive.

Today, Azerbaijan stands in the strongest foreign policy position of its modern history. When rumours and street-level provocations are aimed at a state like this, it signals one thing clearly: its opponents have run out of arguments. And where arguments end, tactics take over. The difference is that tactics without substance are doomed to fail. Every new provocation—from disinformation campaigns to shouts outside the Washington hotel—only reinforces this reality.

Azerbaijan has learned to distinguish between noise and real threats. It knows how to separate tactical distractions from strategic challenges. Most importantly, it has learned to act—calmly, deliberately, and effectively—without slowing its momentum or being sidetracked by provocations. It is this steadfastness that frustrates its opponents the most. Because you cannot stop a country that knows where it is headed; the only response left is impotent outrage.