EU leaders’ summit challenges the “Brussels wisdom” New era or chaos ahead?

Brussels hosted “the most consequential European Council since the pandemic,” from which historic decisions were expected. The summit did not end in complete failure, but it clearly highlighted the risks of a governance crisis within the EU and the potential erosion of its political unity.

On December 18–19, the European Council held a meeting in Brussels. This is the EU’s main political body, bringing together the heads of state and government of all member countries and making the most important decisions that require intergovernmental approval. The meeting itself was scheduled in advance, but its agenda and the heated political and media debates surrounding it made it extraordinary. Even before the summit, the European press had called it “the most consequential European Council since the pandemic,” while Brussels’ diplomatic circles spoke of a historic moment of truth and “ a new era for Europe.”

It is hardly surprising that the EU leaders’ meeting attracted intense attention literally around the world. In the end, the drama of the summit was confirmed by its chronology. The leaders of united Europe spent 17 gruelling hours in negotiations and only concluded their work at 3 a.m. on December 19. After that, they chose not to continue discussions on the second day and returned to their capitals.

One issue instead of three

Formally, the European Council’s agenda included three items: financing Ukraine’s economic and military needs, finalising a major trade agreement between the EU and South American countries, and the next EU multiannual budget. One way or another—especially politically—all three issues were interconnected. However, the first issue completely overshadowed the Mercosur trade agreement with the combined South American market. The future EU budget, according to official reports, was also discussed only briefly, mostly in the context of support for Ukraine.

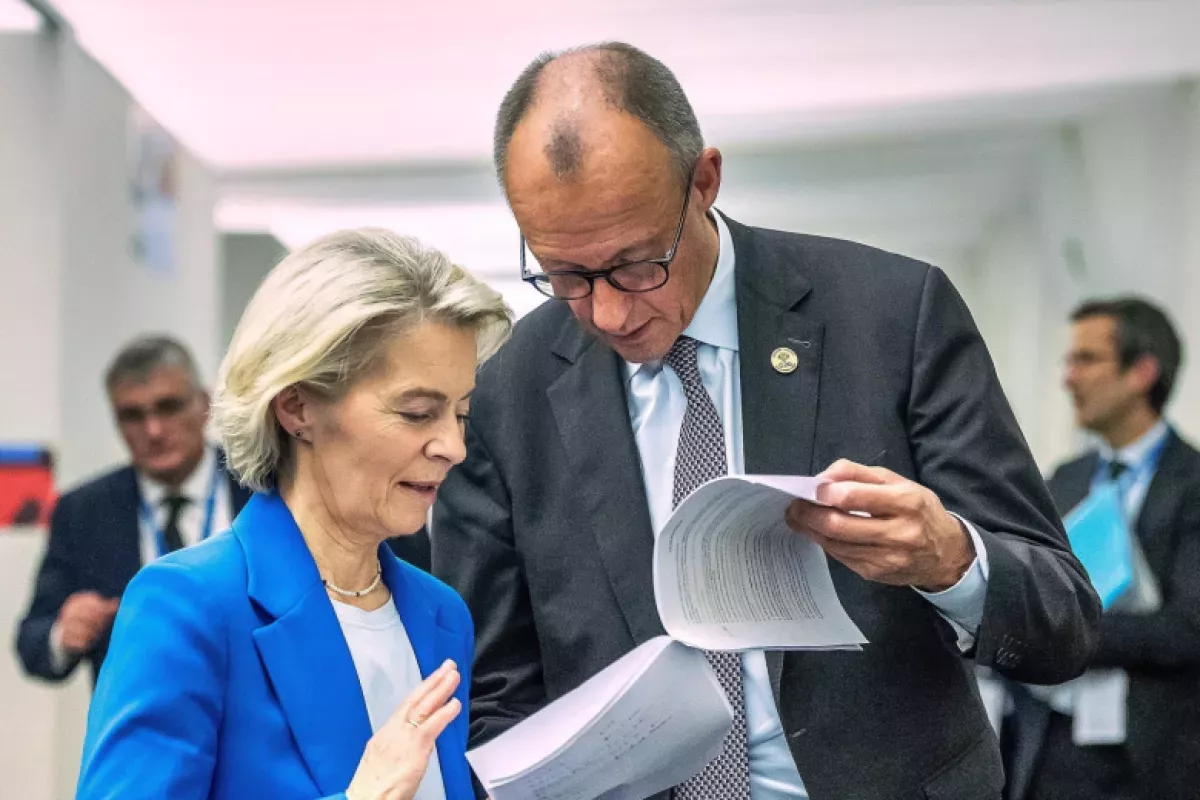

This vividly reflects the intensity and specificity of the moment. It is enough to mention that trade with Mercosur is by no means a routine topic for the European Union. Attempts to conclude a large-scale agreement between the two blocs have been ongoing for nearly a quarter of a century. At present, the parties were closer than ever to this goal: European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen was already planning to visit Brazil—the Mercosur chair—on December 20 to finally sign the trade agreement ceremonially. However, in the end, the European Council decided to postpone the event by at least another month.

This delay is not directly related to the Ukraine case. The new postponement was caused by pressure from the agricultural lobby in several EU member states, which opposed the current draft agreement, and by Italy’s last-minute change of position as a result. Yet the urgency of Ukraine-related issues left EU leaders insufficient time to discuss trade with South America.

It was precisely this urgency on the Ukrainian matter that gave the summit added significance and sparked behind-the-scenes talk of a “new era for Europe.” This was primarily connected to the long-discussed issue of using frozen Russian assets held in EU banks to finance Ukraine’s economic and military needs.

According to publicly stated calculations, without financial assistance from Western partners, Kyiv could face a major budget crisis as early as next spring. Simply put, the Ukrainian authorities will have nothing to cover the budget deficit, which is estimated at over €71 billion in 2026. In 2026–2027, according to IMF estimates, Ukraine will need around €130 billion in external financing to cover its remaining budget shortfall.

EU’s response to the Chamberlain moment

Why was the need to address Kyiv’s budget problems—which have existed for some time—now framed as a historic moment of truth and a “new era” for the European Union itself? German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, who was particularly vocal in support of seizing frozen Russian assets, framed the EU’s challenge ahead of the summit as follows: if a decision on the seizure is not reached, “we will show the world that, at such a crucial moment in our history, we are incapable of standing together and acting to defend our own political order on this European continent.”

Behind such grand statements, in fact, lie several challenges for the European Union. The summit was intended to send political signals—or, as it is now fashionable among European officials to say, “messages”—to at least three audiences.

First, to the citizens of the EU member states themselves. Fresh opinion polls show that prospects for continued support of Ukraine are increasingly met with scepticism across the EU. Different member states show varying levels of support and differing trends in public opinion. However, a notable surge in scepticism has been observed in two key countries—Germany and France—where the share of those advocating for a reduction in financial aid to Kyiv now exceeds those in favour of increasing it.

For most EU leaders, it was therefore crucial that the European Council not only demonstrate firm unity in supporting Kyiv, but do so precisely now, before the political influence of far-right forces opposing this course grows further in some EU countries.

Second, to Moscow. Against the backdrop of a worsening battlefield situation for Ukraine and increasingly active efforts by the Donald Trump administration to find a diplomatic way to end hostilities, the EU was starting to appear irrelevant in the broader mosaic of actors and factors shaping events. In this context, a potential decision to seize Russian assets in favour of Ukraine was seen in Brussels as a last-resort argument—a way to alter some key assumptions on the battlefield and in diplomacy, thereby reviving the EU’s geopolitical significance, and as a means to undermine Russia’s calculations regarding the future course of the war.

Finally, perhaps the most important audience was Washington and Donald Trump personally. On the eve of the December 18–19 summit, European media wrote that it was “a test of whether the EU can maintain unity under U.S. pressure.” This atmosphere in Brussels and other European capitals had been building for several months and peaked after the release of the new U.S. National Security Strategy. Its authors, as noted earlier, showed little political correctness regarding the EU. According to references circulating in the European press citing unnamed sources, the U.S. administration reportedly did not hide its opposition to the idea of seizing Russian assets for Ukraine’s benefit. It is claimed that the Americans even pressured certain EU member states to prevent such a decision.

Plan B starts to win

In light of these considerations, most EU national leaders and Brussels bureaucrats were betting that the European Council could finally decide on the full seizure of Russian assets. This option was considered “Plan A” for financing Ukraine’s further military and budgetary needs. A week earlier, on December 12, the EU had already decided to “immobilise” these assets. They can no longer be returned to Russian counterparties or used by them without additional approvals from EU member states. This also eliminated the risk that, during the next six-monthly review of the sanctions regime against Russia, a single EU country could block the extension of restrictions and restore Moscow’s access to the resources.

However, the EU was unable to go further. Belgium, which holds the lion’s share of frozen Russian assets under its jurisdiction, had rejected the idea of expropriating them for several months. Belgian authorities demanded firm guarantees from other EU countries that, in the event of Russian countermeasures, the risks and financial costs would be evenly shared across all member states. In the end, they did not receive such guarantees and were faced only with an intense campaign of pressure.

At one point, even the majority of supporters of asset seizure began discussing a course of action that until recently had seemed unthinkable—making a decision through the so-called “qualified majority” procedure, rather than by consensus of all EU member states. Legally, this mechanism is allowed in emergency cases, but given the topic’s specificity and political significance, concerns were not unfounded that such a “forced measure” could provoke a serious governance crisis within the EU.

Moreover, as the European Council meeting approached, several more countries voiced opposition to the idea of expropriating Russian funds. Belgium was joined not only by the traditional opponents of such measures, Hungary and Slovakia, but also by Italy, Bulgaria, Malta, and the Czech Republic.

As a result, “Plan B” began to be seriously discussed. It involved EU member states jointly borrowing funds on behalf of Ukraine. This was precisely what some countries opposing “Plan A” insisted on. However, implementing this plan requires the unanimous approval of all 27 member states, which immediately seemed impossible given Hungary’s unwavering stance. From a political perspective in many EU countries, the plan also appeared risky, as it would provide fresh arguments for the increasingly popular far-right.

Nevertheless, this option was approved by the European Council after 17 hours of gruelling discussions—albeit with caveats. Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic will not participate in its implementation. To adopt this decision and bypass the requirement for consensus, the EU invoked another, essentially emergency, mechanism provided for in Article 20 of the Treaty on European Union.

Is the issue of seizing Russian assets closed?

Even looking at the approximate forecasts for Ukraine’s budget deficit in 2026–2027—€130 billion—it is clear that the decision made at the European Council to allocate €90 billion is insufficient. It is obvious that the situation in Ukraine will change rapidly next year, and current estimates of Kyiv’s financial needs may become outdated within a few months. Most likely, the needs will only increase, especially if American efforts to halt hostilities do not succeed in the first half of next year.

EU member states and institutions will, in any case, have to rack their brains to find additional sources of financing for Ukraine. At the final press conference on the morning of December 19, EU leadership emphasised that the issue of seizing Russian assets is not closed and that work in this direction will continue. This is yet another challenge hanging over the European Union.

But the main challenge facing the EU lies elsewhere. As Politico aptly noted, “more European leaders than ever […] reject Brussels’ accepted wisdom.” Within the EU, this is seen as a challenge to European unity—and rightly so.

Even more fundamentally, it is a challenge to that very “Brussels wisdom.” It raises a critical question about the relevance of such “wisdom” in a rapidly changing world. More broadly, it confirms a seemingly banal but essential truth: if policy-making is reduced to repeating conventional mantras, sooner or later it will come into conflict with your own interests. And with such contradictions, it will be very difficult for the EU to enter a “new era.”