Georgia between transit and territorial challenges Article by Vladimir Tskhvediani

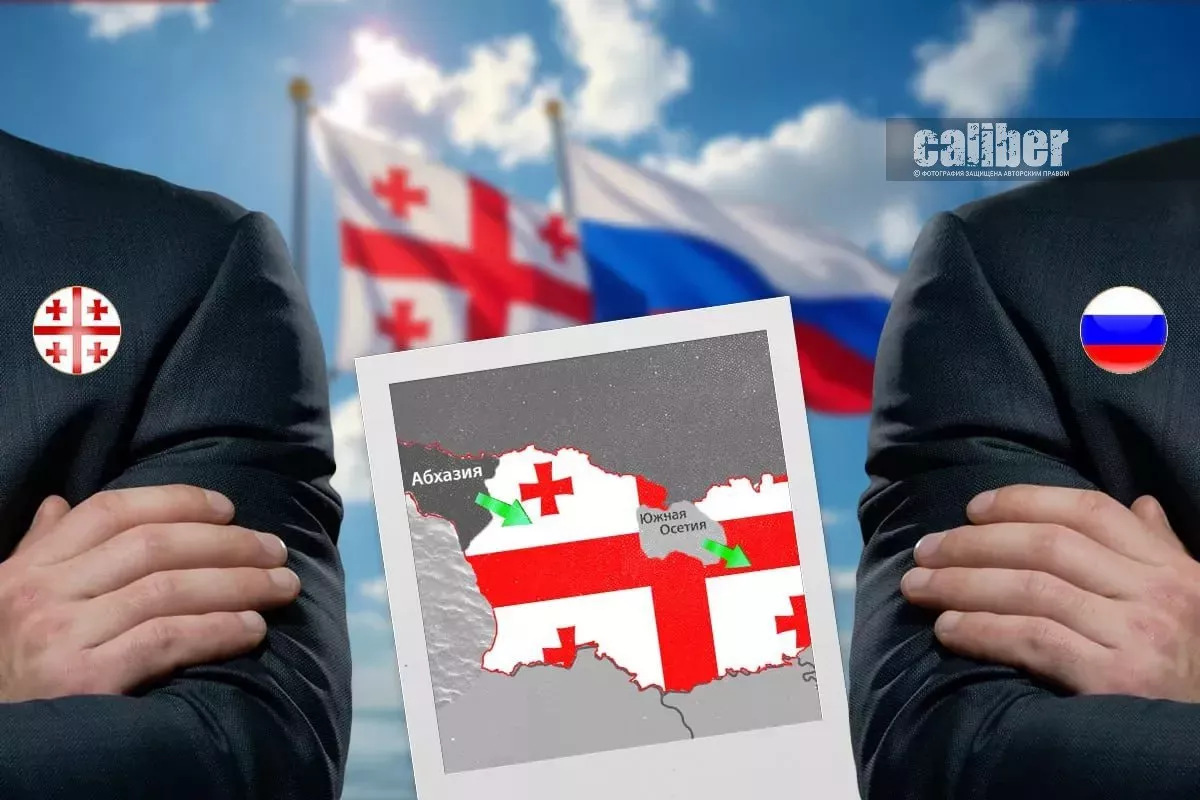

Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze has once again emphasised his country’s pragmatic policy towards Russia, despite the absence of diplomatic relations and the ongoing territorial conflicts. In an interview with Rustavi 2, he stressed that “there are red lines related to the issue of occupation.” According to Kobakhidze, without a change in the status of Abkhazia and the so-called “South Ossetia,” the restoration of diplomatic relations is impossible.

“We do not have diplomatic relations, but at the same time, we maintain trade and economic ties,” the prime minister said, adding that Tbilisi’s policy is aimed at a peaceful resolution of the conflict.

Georgian leadership's refusal to restore diplomatic relations with Russia without the de-occupation of Georgian territories, however, does not hinder the growth of trade between the two countries. For example, the trade turnover between Georgia and Russia from January to November 2025 increased by 5.4% compared to the same period in 2024, reaching $2.4 billion. According to Sakstat, Russia is among Georgia’s top three trading partners: its share in Georgia’s foreign trade turnover for the 11 months of 2025 amounted to 10.3%.

Russia remains Georgia’s largest grain supplier. From January to November this year, 360,400 tonnes of wheat and meslin were imported from Russia. In addition, Georgia imported 658,200 tonnes of oil and petroleum products, 572,500 tonnes of natural and associated gas, 133,600 tonnes of crude oil and petroleum products, and 33,200 tonnes of sunflower, safflower, or cotton oil and their fractions from Russia. For several product categories, exports from Russia to Georgia increased several times — in particular, crude oil exports grew nearly 13-fold, primarily due to the commissioning of the oil refinery in the Georgian port of Kulevi.

Conversely, since the beginning of the year, Georgia exported 124,300 tonnes of mineral and spring water, 56,000 tonnes of natural grape wine, 55,500 tonnes of mineral and carbonated water with sugar, 36,000 tonnes of alcoholic beverages, and 10,200 tonnes of fresh fruits to Russia.

The flow of Russian tourists is also of significant importance to Georgia’s economy. Russian visitors remain one of the key sources of revenue for the country’s tourism sector. For example, while total income from international tourism in Georgia in the third quarter of 2025 reached $1.66 billion, $252.5 million came from Russia, $238.2 million from EU countries and the United Kingdom, $195.7 million from Türkiye, and $188.3 million from Israel.

Although the current pro-Western Georgian opposition links the influx of Russian tourists to the supposedly “pro-Russian” policies of the ruling Georgian Dream party, it is worth recalling that the flow of Russian visitors to Georgia, as well as the growth in trade with Russia, began to increase rapidly during Mikheil Saakashvili’s presidency — it was under his initiative that the visa regime for Russian citizens was abolished.

Most Russian tourists visiting Georgia encounter an exceptionally friendly and welcoming attitude. Anti-Russian demonstrations or gestures by overly politicised compatriots are generally avoided by Georgians themselves. This is understandable, as the incomes of many Georgian families depend directly on Russian tourists. Furthermore, a significant portion of the population clearly distinguishes the Russian authorities from ordinary Russians and even tries not to project their negative attitudes toward the former onto the latter.

It is also a myth that there is heightened “anti-Russian sentiment” or universal “pro-European” attitudes among Georgian youth — especially in the regions. Poor knowledge of the Russian language does not necessarily indicate a negative attitude toward Russia. Moreover, interest in learning Russian is growing among young people for purely pragmatic reasons: knowing the language greatly facilitates obtaining well-paid jobs in sectors serving guests from post-Soviet countries.

Even Georgians who do not speak Russian often have a positive attitude toward Russians — particularly among the more religious segments of society. As is well known, the Georgian Orthodox Church plays a significantly more prominent role in the country than, for example, Etchmiadzin does in neighbouring Armenia. For Orthodox Georgians, the shared faith with Russians often carries decisive importance, pushing political issues into the background.

Overall, the opposition’s reliance on anti-Russian sentiment in society during attempts to organise a “Maidan” did not pay off. Although opposition figures labelled the ruling Georgian Dream party as “Russian rule” or “Russians” and even used openly offensive terms like “Russian slaves,” this did not help them attract additional protesters.

The reason is simple: anti-Russian sentiment in Georgian society was and remains significantly exaggerated. Moreover, it has been inflated not only by Western and pro-Western media and NGOs. For a long time, Georgia’s so-called “anti-Russian stance” was actively hyperbolised by Kremlin-linked propaganda in Russia. Any, even openly marginal, anti-Russian action was instantly “magnified” and presented as evidence of almost total Russophobia in Georgia.

The reason for this is no secret. This propaganda line was closely linked to the Armenian lobby in Russia, which for decades sought to portray Armenia — supposedly Russia’s “outpost” and “loyal ally” in the Caucasus — in opposition to a “hostile” and “ungrateful” Georgia, allegedly trying to enslave the “freedom-loving” Abkhazians and Ossetians. The purpose and beneficiaries of this so-called “love of freedom” have long been clear. By analogy with Abkhazia and the so-called “South Ossetia,” it was assumed that Russia, in its own interests, would support the separatist project of the so-called “Artsakh.”

Moreover, in separatist Abkhazia, the local Armenian community has effectively taken control of a significant part of the economy and seriously counted on the complete “Armenisation” of the territory. As a result, it has consistently opposed — and continues to oppose — reconciliation between the Abkhaz and Georgian peoples and the return of Georgian refugees.

However, times are changing. The current authorities in Armenia can be regarded as Russia’s “allies” only with considerable reservations. Pro-Russian political forces in Yerevan have been removed from power, and the separatist “Artsakh” has been liquidated once and for all. Nevertheless, propaganda inertia in Russia largely persists, as it remains tied to the same lobby. As a result, despite a weakening of anti-Georgian rhetoric, myths about “anti-Russian sentiment” in Georgia continue to be sustained. Increasingly, anti-Russian slogans at rallies of the pro-Western opposition — which are becoming ever more marginal — are cited as “evidence.”

Finally, one cannot ignore the factor of growing disillusionment with Europe and so-called “European values” within Georgian society, including among young people. In the media space — especially the pro-Western segment — this topic is largely taboo. Yet many Georgians who have visited Europe have seen for themselves that no “earthly paradise” exists there and that it has plenty of problems and contradictions. The willingness to go to war with Russia for the sake of approaching such a “European paradise” is visibly declining. All the more so since even the most radical opponents of Russia show no readiness to fight it directly. Their position boils down to a desire to “join the winners,” shifting the main costs of a hypothetical “defeat of Russia” onto someone else — Ukraine, Europe, NATO, and so on.

It is no coincidence that criticism of the ruling Georgian Dream party’s pragmatic policy toward Russia within Georgia itself intensified sharply in the second half of 2022 — against the backdrop of the Ukrainian army’s successes on the front at the time. However, once those successes faded, the number of belligerent anti-Russian statements inside the country, including from the opposition, also declined noticeably. The prospect of fighting for years and bearing human losses, as is happening today in Ukraine, is increasingly uninspiring even for the most hardline anti-Russian segment of Georgian society.

Undoubtedly, the issue of Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region remains a key “red line” shaping Georgian society’s attitude toward Russia. The possibility of “ceding territory” in exchange for restoring diplomatic relations with Russia is not considered under any circumstances. At the same time, this clearly demonstrates how, through relatively simple steps, Russia could “win over” Georgia — if not as an ally, then at least as a partner. For this, it would be sufficient to begin a genuine process of de-occupation of the seized Georgian territories or otherwise recognise their belonging to Georgia.

For now, the Kremlin is attempting to organise transit through Abkhazia without proceeding with its de-occupation. This concerns the implementation of an agreement signed in November 2011 under U.S. mediation, during the presidency of Mikheil Saakashvili and his party, the United National Movement (UNM), aimed at removing obstacles to Russia’s accession to the World Trade Organisation. According to this document, “extraterritorial trade corridors” were to be established at the Russia–Georgia border, including on extended sections passing through the occupied zones. At the same time, the occupied territories and the separatist regimes are not mentioned in the agreement — there is no question of recognising them — and control over the cargo was agreed to be entrusted to the Swiss company SGS.

However, after media reports emerged about the construction by the Russian side of a customs hub in occupied Abkhazia — in Gali, near the boundary of the occupation zone — the Georgian government took a firm stance and publicly distanced itself from the facility. Commenting on the prospects of transit through occupied Abkhazia under the “corridor” framework of the 2011 agreement, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze reminded that the document was signed during the rule of the UNM party, which is now in opposition.

“We do not recognise any so-called state border […], and therefore there can be no discussions on this issue from our side,” emphasised Kobakhidze.

This reminder — that the restoration of diplomatic relations with Russia is impossible without the revocation of the “recognition” of the so-called “independence” of the occupied territories — is primarily directed at the Kremlin.

Under current circumstances, against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, Russia’s geopolitical position has become considerably more complicated, and transit through Georgia’s still-occupied territories is objectively much more necessary for Russia than for Georgia itself. At the same time, Tbilisi’s principled position on the restoration of territorial integrity enjoys broad international support — primarily from Türkiye, Azerbaijan, and the United States. In these conditions, it is unlikely that the Georgian authorities would agree to transit through Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region without concrete and tangible steps from Russia toward the de-occupation of these territories.

By Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, exclusively for Caliber.Az