Evolution of French colonialism: Unveiling legacy - Article two Corbin’s report

Continuing our series on The Evolution of French Colonialism based on the eponymous analytical report by international governance expert, Carlyle Corbin, the second part of the document focuses on the strengthening of France's colonial policies in the period following the French Revolution.

Establishment and legitimization of colonial policy

France in the 19th and early 20th centuries

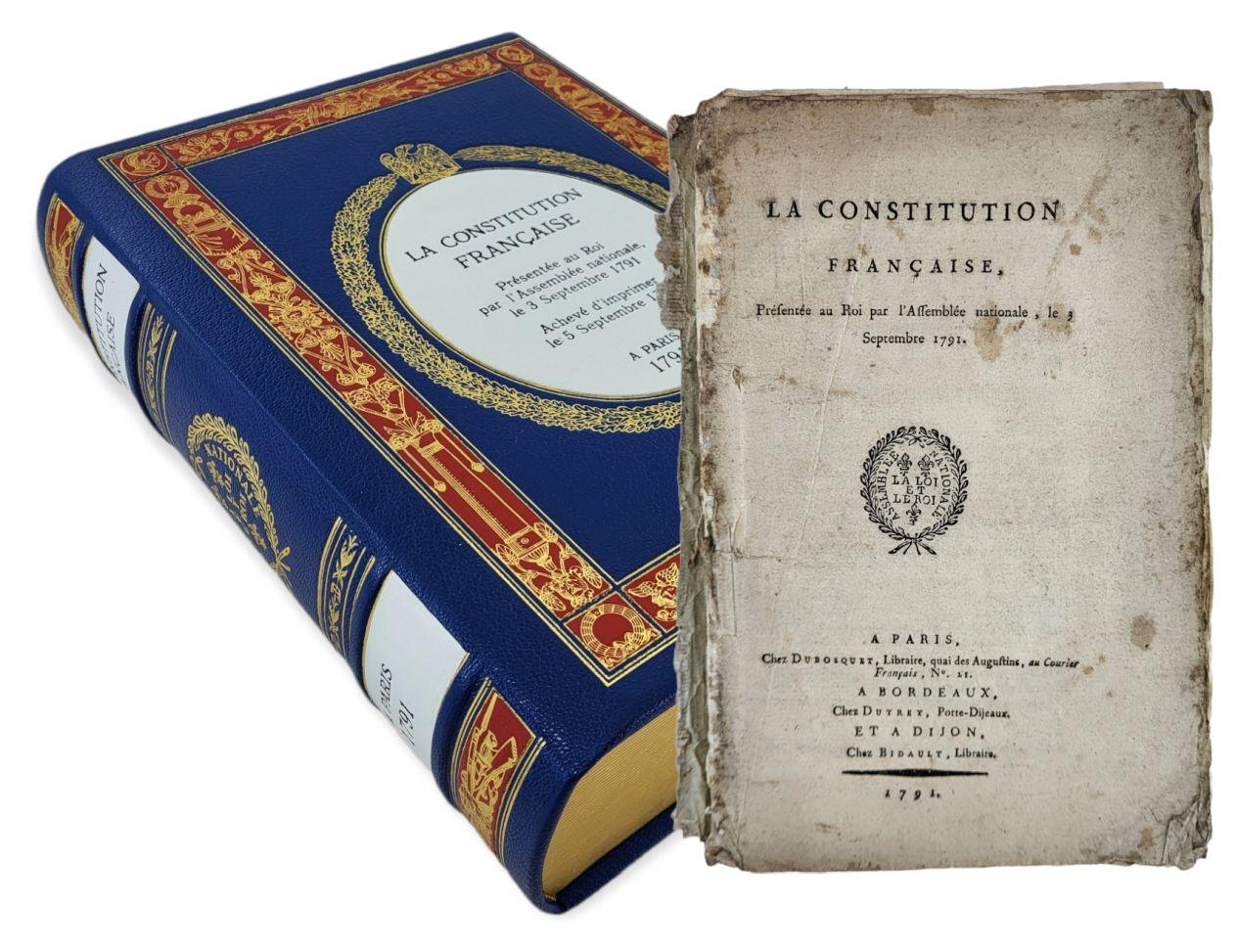

The first French Constitution of 1791 contained only a vague reference to the extensive overseas possessions of the metropolis. The text of the fundamental law stated: "The French colonies and possessions in Asia, Africa, and America, although constituting part of the French dominion, are not included in the present Constitution." The 1793 constitution made no mention of the colonies at all. However, this changed in 1795.

In the so-called "Constitution of Year III," the administration of the colonies was assigned to the "Directory," a five-member body appointed by the Legislative Corps of the country: “Until peace has been made, all public functionaries in the French colonies, except in the departments of the Île de France and the Île de la Réunion, shall be appointed by the Directory. The Legislative Body may authorize the Directory to send to all French colonies, as occasion may require, one or more special agents appointed by it for a limited time. Such special agents shall perform the same duties as the Directory, and shall be subordinate thereto.”

In 1804, the Napoleonic Code came into effect, reinstating colonial slavery and extending the laws to all territories under Parisian control. The French Senate, in turn, bestowed the title of Emperor upon Napoleon Bonaparte. That same year, a constitutional referendum established the First French Empire. After Napoleon was forced to abdicate, subsequently exiled to the island of Elba, escaped in 1815, and was ultimately defeated at the Battle of Waterloo, he was exiled to Saint Helena. Louis XVIII became King of France and reigned until 1824. This was followed by the July Revolution of 1830, which saw Louis-Philippe become King of France, and the February Revolution of 1848, which led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Second Republic.

The unification of French colonies was first constitutionally enshrined in the provisions of the 1848 Constitution of the Second Republic and included in government documents. Notably, there was an article proclaiming that "slavery cannot exist on any French territory":

"The French National Convention abolished slavery in 1794 in response to slave uprisings in France’s Caribbean colonies and the French Revolution. This radical act made France the first imperial nation to universally outlaw slavery. Yet, just eight years later, France became the only state in the history of the Atlantic world to comprehensively re-establish slavery in its empire. While black citizens resisting the return of slavery established Haiti as the Caribbean’s first postcolonial nation in 1804, colonists in Guadeloupe, Martinique, and French Guiana orchestrated the mass enslavement of free people of African descent who claimed French citizenship. The imperial authorities reinstated slavery and the slave trade and empowered colonial settlers to hold freed people as property until 1848."

At the same time, the Constitution of the Second Republic declared Algeria and other colonies as French territories, guaranteeing them 13 seats in the National Assembly. This minimal representation in the 750-seat legislative body was also vastly disproportionate to their population. For instance, Algeria received three seats; Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Réunion each received two seats; while Guyana and Senegal were allocated just one seat in parliament.

On the ground, the situation remained extremely difficult. All those who were not of European origin, including Algerians, continued to be colonized. The people of Algeria were deliberately excluded from French citizenship, being classified as natives. The right to vote, granted in 1848, was revoked just a year later and was not reinstated until 1870.

The 1851 referendum approved a new French constitution in 1852, which delegated unlimited power to Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, better known as Napoleon III. This effectively established a regime of direct colonial rule. Meanwhile, the French Senate was granted the right to regulate colonial legislation through a consultative council.

The Constitution of the Third French Republic in 1870 officially established the institution of colonial representation in the National Assembly and the Senate. The stark disproportion between the number of representatives from France and its colonies remained evident, contradicting any notion of political equality. For instance, in 1931, 41.8 million French citizens were represented in the country’s legislative bodies by 606 deputies and 307 senators, while the interests of 64.7 million people living in territories occupied by France were represented by just 19 deputies and 7 senators.

Leonard Smith, a history professor at Oberlin College, explains the reasons for such political inequality by citing a well-known statement made by France’s minister for colonies and war minister, Adolphe Messimy, who said in 1907: "if they followed the principle of equal representation, the colonies would send some 700 deputies to Paris. He argued that such a hypothesis ‘by its very absurdity’ showed how colonial representation could upend French political life."

Meanwhile, from the beginning of the 20th century until 1940, French laws maintained supremacy in the colonies, despite the creation of colonial institutions with limited powers, such as the General Council and the Administrative Council. The governance of the colonies during this period was carried out, on the one hand, through decrees issued by the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Colonies in Paris, and on the other, through edicts by the governors-general, who were entrusted with some executive and judicial authority, particularly in territories far removed from France. Protectorates were also established. To create the appearance of autonomy, the French left only symbolic legislative power to the local ruling elites.

During the Fourth Republic (1946-1958), France positioned itself as an " indivisible, secular, democratic, and social" republic. The new constitution declared that France “shall form with the peoples of her Overseas Territories a Union based upon equality of rights and privileges, without distinction as to race or religion.” However, the same constitution also provided for the continued dominance of Paris over the colonies:

“The Union Française (French Union) shall be composed, on the one hand of the French Republic which comprises Metropolitan France and the Overseas Departments and Territories (DOMs/TOMs) and, on the other hand, of the Associated Territories and States. The position of the Associated States within the French Union shall, in the case of each individual State, depend upon the Act that defines its relationship to France.”

Thus, the term "colony" was effectively excluded from the 1946 Constitution and replaced with "overseas departments," "overseas territories," "associated territories," and "associated states." The Ministry of Colonies was transformed into the Ministry of Overseas Territories.

It should be noted that this was not just a linguistic nuance but a deliberate attempt to conceal and disguise ongoing colonialism under the guise of democratic reforms. The formal removal of the term "colony" from the Constitution was meant to create the illusion of equality and integration, while in reality, the former system of metropolitan dominance over dependent territories remained intact.

Japanese law professor Masahiro Igarashi, in his seminal book "Associated Statehood in International Law," noted that the 1946 Constitution provided constitutional cover for annexation and likely reflected the idea of "preserving the empire," despite the obvious geographical distance and cultural differences between the renamed colonies and the metropole. Consequently, the emergence of a determined policy of assimilation, aimed at projecting the superiority of French culture and absorbing local cultures, was inevitable.

Under its new structure, the administrative configuration included overseas departments such as Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Guyana in the Caribbean, as well as Algeria, Réunion, and Senegal in Africa. The overseas territories comprised the federations of West Africa and Equatorial Africa. The associated states included Morocco, Tunisia, Madagascar, and Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia). Syria and Lebanon gained independence. The associated territories included Togo and Cameroon.

Article 75 of the 1946 Constitution stipulated that any changes in political status or transitions from one category to another required the passage of a corresponding law by the French Parliament, following consultations with local assemblies and the Union Assembly. Thus, this period marked the beginning of a mechanism of "mutual consultations," which was not intended to rise to the level of "mutual consent."

In other words, consultations with local assemblies were merely a formality rather than a genuine process of agreement. The French government could listen to the opinions of local authorities, but the final decision rested solely with the French Parliament. As a result, local assemblies had no real ability to influence changes in their political status, and "mutual consultations" served more to simulate participation and legitimize decisions than to achieve actual consensus.

The third part is available here.

By Samir Guliyev