Risks behind Washington's self-contradictory trade policy on minerals

Securing access to critical minerals has become a key priority in US foreign policy. President Trump is seeking Ukraine’s rare earth reserves, along with other natural resources, as compensation for past and future military or financial aid. Given their role in emerging technologies like renewable energy and AI, critical minerals have been called the "gold rush of the 21st century."

While Trump has pledged to make the US "the leading producer and processor of non-fuel minerals, including rare earth minerals," an article by the US Newsweek magazine highlights the country's overwhelming reliance not just on foreign imports but oftentimes it's biggest political adversaries.

This dependence poses financial and geopolitical risks, as adversarial nations controlling supply chains could leverage this reliance.

However, these imports, especially rare earth minerals, are essential to various sectors of the US economy. Beyond materials like graphite and asbestos used in manufacturing and construction, minerals such as lithium are crucial for electric vehicle batteries and green energy technology.

As the US Geological Survey (USGS) data indicates, the US sources a significant share of its minerals from allies like Canada, Brazil, and Germany. Canada is a major supplier of cesium, used in electric vehicle batteries.

According to the USGS, the US is entirely reliant on imports for 12 of 50 critical minerals and more than 50 percent reliant on imports for another 28.

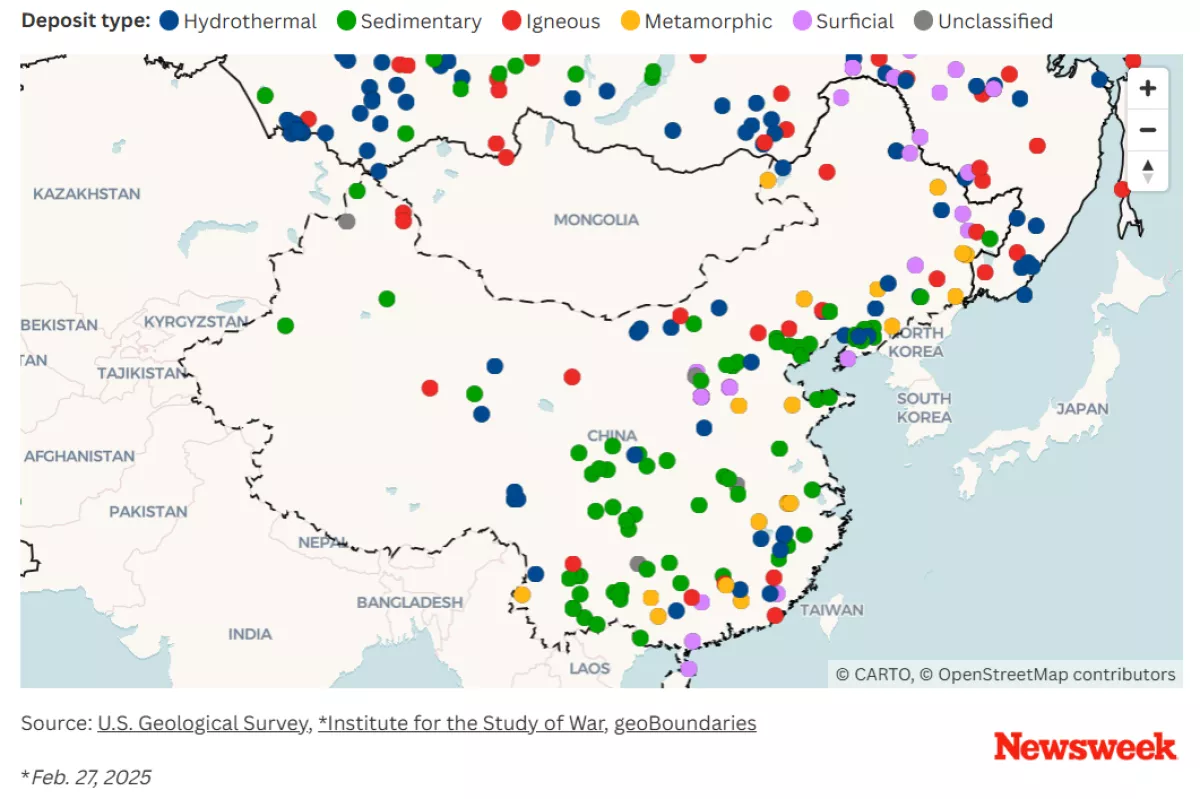

Ryan Kiggins, a political science professor at the University of Central Oklahoma, told the publication that the US has grown increasingly dependent on China for the past 40 years for both raw and refined rare earths. "This dependency arose as the US chose to forgo domestic mining and refining, unwilling to bear the significant investment and environmental costs," he argued.

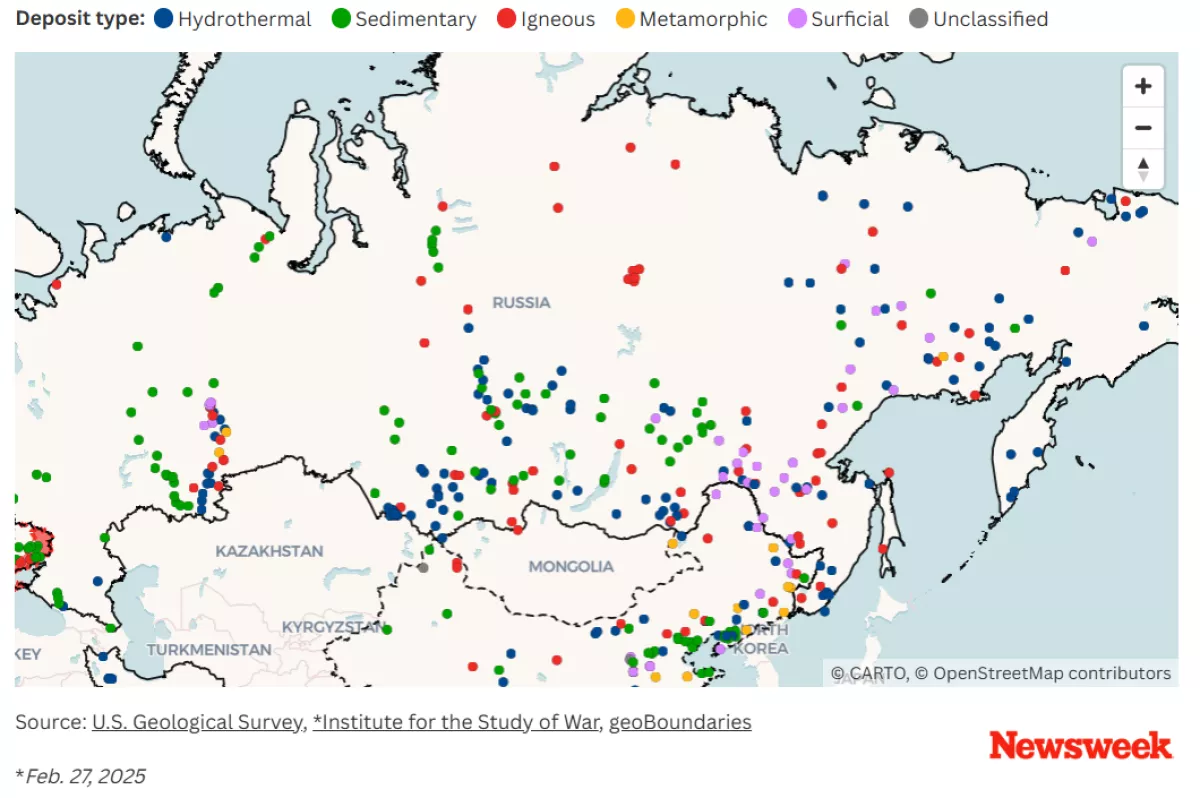

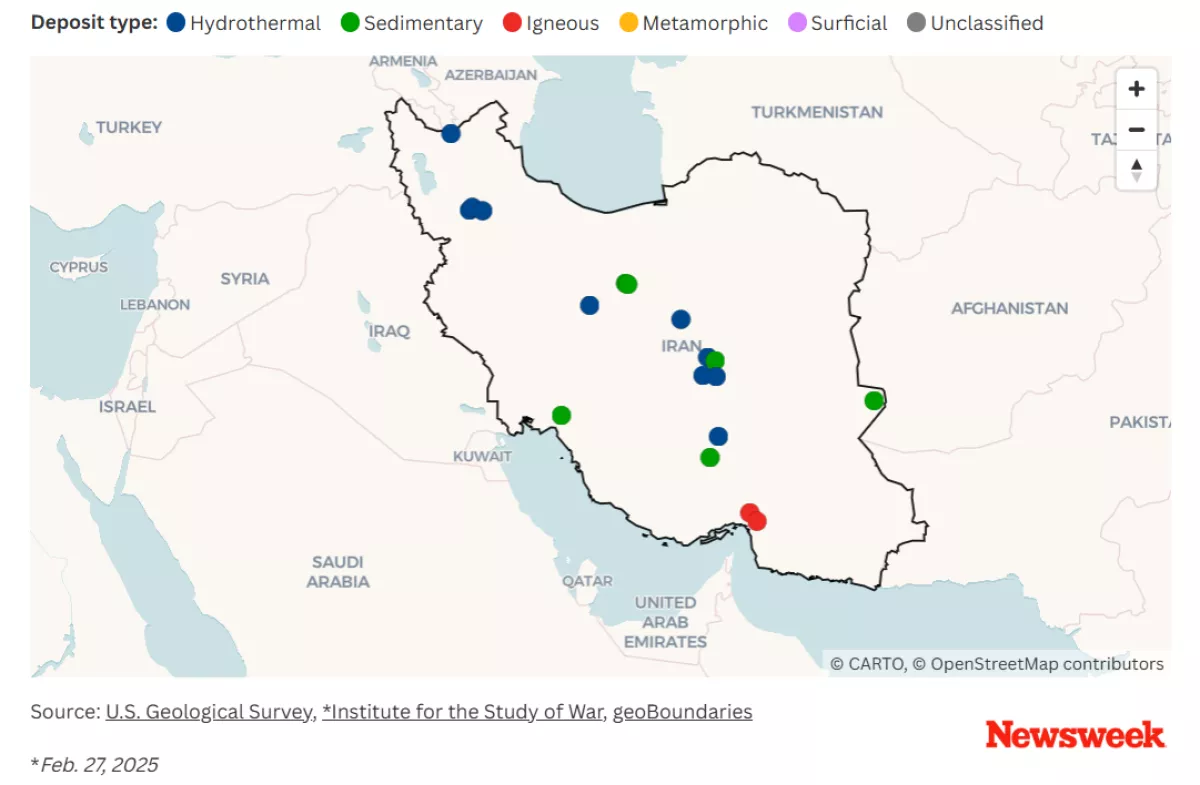

The global supply of critical minerals is dominated by the so-called Axis of Upheaval—an informal term for Iran, Russia, and China, regarded as America's key adversaries in the 2020s. These nations possess substantial mineral reserves that could complicate US economic and strategic interests.

Friend vs foe?

Despite a decline in imports following the outbreak of Russia’s military invasion on Ukraine in 2022, the USGS notes that Russia remains a key supplier of certain minerals to the US, including palladium.

In response, Montana Senator Steve Daines proposed a bill in September to ban Russian critical mineral imports and boost domestic extraction efforts.

The war in Ukraine has bolstered Russia's mineral access, as it now controls territories rich in copper, lead, manganese, iron, and rare earth elements. President Vladimir Putin has even suggested cooperating with the US to extract these minerals as part of possible future negotiations.

Iran, too, holds mineral wealth, though its economy depends far more on oil and gas. However, due to extensive US sanctions—imposed for nuclear violations, support for militant groups like Hamas and Hezbollah, and human rights abuses—America does not import minerals from Iran.

China remains one of the US's largest mineral suppliers, second only to Canada in total net import reliance. It is the leading provider of key critical minerals such as graphite, tantalum, and rubidium.

These materials have significant industrial and military applications. Recognizing this, Beijing announced in December a ban on exports of gallium, germanium, antimony, and "superhard materials" to the US

According to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, China also dominates the rare earth supply chain, producing 70 percent of the world’s supply and processing 90 percent of global rare earth elements.

By Nazrin Sadigova