Evolution of French colonialism: Unveiling legacy - Article three Corbin’s report

We are pleased to present the third article in our series, The Evolution of French Colonialism, based on the comprehensive analytical report by international governance expert Carlyle Corbin. This instalment (Article 1, Article 2) explores the French metropole's efforts to modernize its colonial policies during the latter half of the 20th century, a period marked by significant global changes and post-war transformations.

Modernizing French colonial policy in the post-war era

As previously noted, the Constitution of the Fourth Republic combined features of both a unitary republic and elements of federalism. The empire was legally abolished and replaced by a form of consensual union known as the French Union. An attempt to further refine the colonial modernization project through the decentralization of the French Union was the adoption of the Loi-Cadre Defferre (framework law) in 1956. It is important to note that a "framework law" is a specific type of French legislation that outlines only the broad parameters for reforms. This allows the French government to implement any parts of the law deemed in line with national interests by decree, at their discretion, and in the order they choose, thereby bypassing the traditional legislative process. Leonard Smith, a professor of history at Oberlin College, has defined the significance of the Loi-Cadre Defferre of 1956 as follows:

In some respects, the former colonies would all become protectorates. The Services d’ E'tat (defense, foreign affairs, finance) would remain in the hands of the Hexagon (France), in which the National Assembly would remain the key locus of sovereignty. Overseas territories would continue to send representatives to Paris, though still not remotely in proportion to their populations.…(T)he loi-cadre devolved real power and financial responsibility to a degree unprecedented in the history of the French empire. Contrary to its original intent, it also provided a political and legal framework for decolonization within a few years.

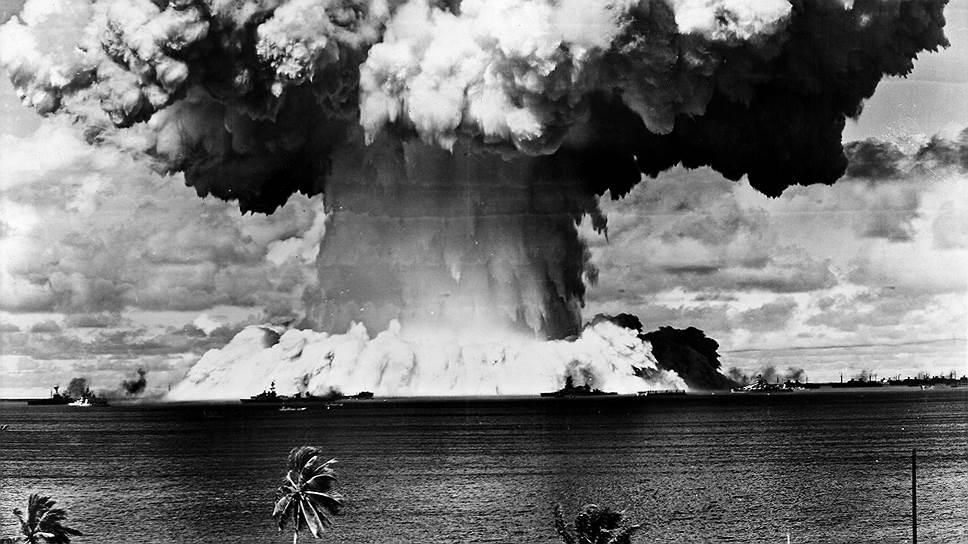

The Framework Law envisioned limited self-government in the overseas territories. However, in the case of French Polynesia, self-government was not even a consideration, as Paris had far-reaching plans to establish a nuclear testing centre on the islands. The old nuclear test sites in Algeria had to be closed due to international public pressure.

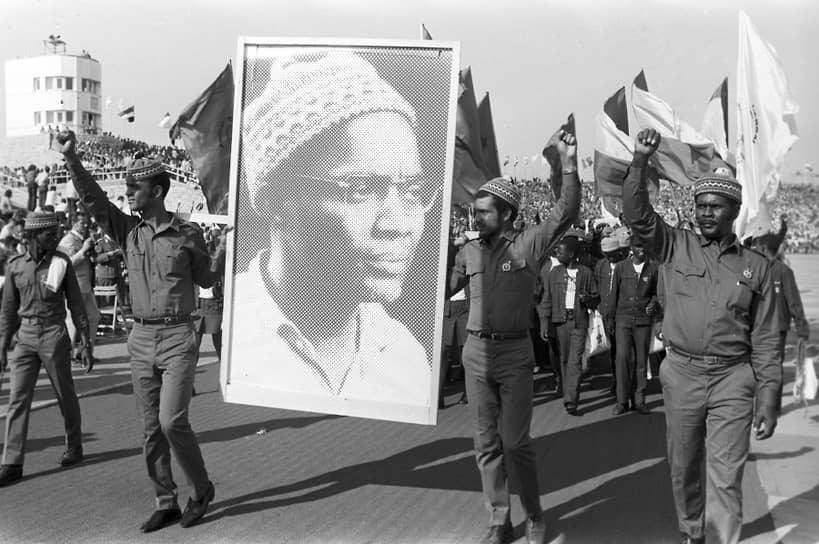

In 1958, a referendum was held based on the Loi-Cadre Defferre to adopt the Constitution of the Fifth Republic. The new fundamental law of France was discussed throughout the French Union. Incidentally, the French Union was planned to be restructured into the French Community. African members of the Union voted in favour of the proposed constitution, subsequently gaining a conditional chance for independence by joining the newly formed French Community. Guinea, the only exception, voted against the constitution by a substantial majority (over 95 per cent). The boldness with which the Guineans rejected the constitution backfired on them and exposed France's colonial mindset. Paris not only withdrew all French civil servants and technical experts from Guinea and ceased all economic and political ties with the former colony but also removed everything it considered its contribution to Guinea, down to the last light bulb. In leaving, the French even burned medicines in hospitals to ensure nothing was left for the Guineans. This was a punishment for Guinea's "stubbornness" and its people's desire to live truly independently, without any associated unions with France.

At the same time, the overseas departments and territories of France, scattered around the world, uniformly voted to adopt the new constitution, marking the beginning of a new phase in the relationship between the metropole and the dominions. National assemblies were given four months to determine the specific mechanism of governance, with three options to choose from: maintaining the status of an overseas territory, obtaining the status of an associated state within the French Community, or becoming an overseas department (full integration). At the end of the specified period, the assemblies of the Comoros (including Mayotte), Saint Pierre and Miquelon, French Polynesia, French Somaliland, and New Caledonia decided to remain as overseas territories, while Chad, French Dahomey (Benin), French Sudan (Mali), Ivory Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Congo, Niger, Senegal, Ubangi-Shari (CAR), and Upper Volta (Burkina Faso) chose the status of an associated state.

However, it cannot be said that the choice was universally voluntary. The Pacific territories that voted to adopt the Constitution of the Fifth Republic had hoped for increased autonomy. In reality, the legitimacy of the referendum in the Pacific region was significantly undermined due to intense pressure from France on opponents of the constitution. This was particularly evident in French Polynesia. The fact that the Polynesians were not adequately informed of their option to reject the constitution and vote against it illustrates France's blatant interference in the referendum results.

Moreover, Polynesian leaders who opposed the constitution became targets for French authorities. Numerous arrests and the show trial of Pouvanaa a Oopa, the leader of the local anti-colonial movement, cast a shadow over the Elysee Palace. Convicted in 1959 on fabricated charges and sentenced to long years of imprisonment, Pouvanaa was extradited to mainland France as a particularly dangerous criminal. He was granted a pardon by Charles de Gaulle in 1968 and fully exonerated only in 2018, decades after his death. His only crime was his opposition to France's plans to conduct nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Ocean.

Despite the lack of a free and fair referendum, over 35 per cent of voters in French Polynesia rejected the constitution proposed by Paris— a higher rate of dissent than in any other overseas territory. The fears of the French Polynesians proved to be well-founded, as France swiftly moved to establish a nuclear testing program that would last more than thirty years. This program led to severe environmental contamination and radiation exposure affecting a large portion of the island’s population (over 119,000 people by 1971). It is also evident that France in 1958 had no intention of granting independence to either the Polynesians of French Polynesia or the Kanak people of New Caledonia. For French Polynesia, the strategic goal was to turn the islands into a major nuclear test site, while in New Caledonia, the key factor was the vast reserves of nickel, a critical resource for heavy industry.

Subsequent attempts by the Polynesians and Kanak people to change the decisions made by local assemblies in 1958 in favour of free associated state status within the French Community, rather than the existing status of overseas territories, were rejected by the French colonial administration. In response, the administration intensified its repression of anti-colonial political forces. The directive from the Minister of Overseas Territories, Bernard Cornut-Gentille, in 1958 fully endorsed France's strategy, which dictated that French Polynesia should not alter its administrative-territorial status under any circumstances, as this would significantly complicate the implementation of France's nuclear testing program in the region. Similarly, a decision favouring free associated state status for New Caledonia would have obstructed France’s continued economic exploitation of the large nickel deposits on this Melanesian territory.

Thus, the establishment of the Fifth Republic resulted in the following outcomes: African territories that chose free association effectively used it as a transitional stage toward independence in the early 1960s, while the Pacific territories remained under the direct oversight of the French National Assembly. Meanwhile, the overseas departments in the Caribbean, which also voted for the new constitution, found themselves in a situation of complete subordination to Paris, effectively becoming integral parts of the French Republic.

As observed, the sweeping constitutional reform initiated by Charles de Gaulle in 1958 did not bring about significant changes in the socio-political landscape of the French colonies. While the names and terms were updated, the core of the colonial policy remained unchanged—exploitation of natural and human resources. Key decisions, even on issues allowing for some level of autonomy, were still made by "representatives" of the French state. Although some former colonies in Africa achieved independence, France managed to retain them within the franc zone—a currency union still under Paris’s control. The Loi-Cadre Defferre (Framework Law) of 1956, which promised substantial autonomy and political decentralization, ended up being little more than a framework.

The fourth part is available here.

By Samir Guliyev