Evolution of French colonialism: Unveiling legacy - Article four Corbin’s report

The report titled The Evolution of French Colonialism, prepared by the American international governance expert Carlyle Corbin, includes, among other things, up-to-date information on the issues of legitimizing French neocolonialism in the contemporary context. These issues will be addressed in the concluding fourth article of the series (Article 1, Article 2, Article 3).

The crisis of French neocolonialism

Remarkably, France holds the world record for the number of time zones, totaling twelve. Of these, eleven are spread across what are known as overseas communities (formerly overseas territories before the 2003 constitutional reform), overseas departments, and New Caledonia, whose status remains unresolved. How did it come to be that, in an era marked by the supremacy of international law, mass decolonization, and decentralization, Paris has managed to maintain influence and control over territories located thousands of kilometers away? More importantly, what are the goals of the metropolis, and what methods does it employ to retain control? Nearly three million people live under conditions of oppression, repression, and financial dependence. What is the purpose of this? Is it to fulfill the ambitions of French political leadership, their desire to see the republic as an empire, or merely to maintain a presence on all continents and oceans as a mark of a great power? This presence is not only manifested through intervention in various economic and social spheres but also through the establishment of naval bases around the periphery of these overseas territories.

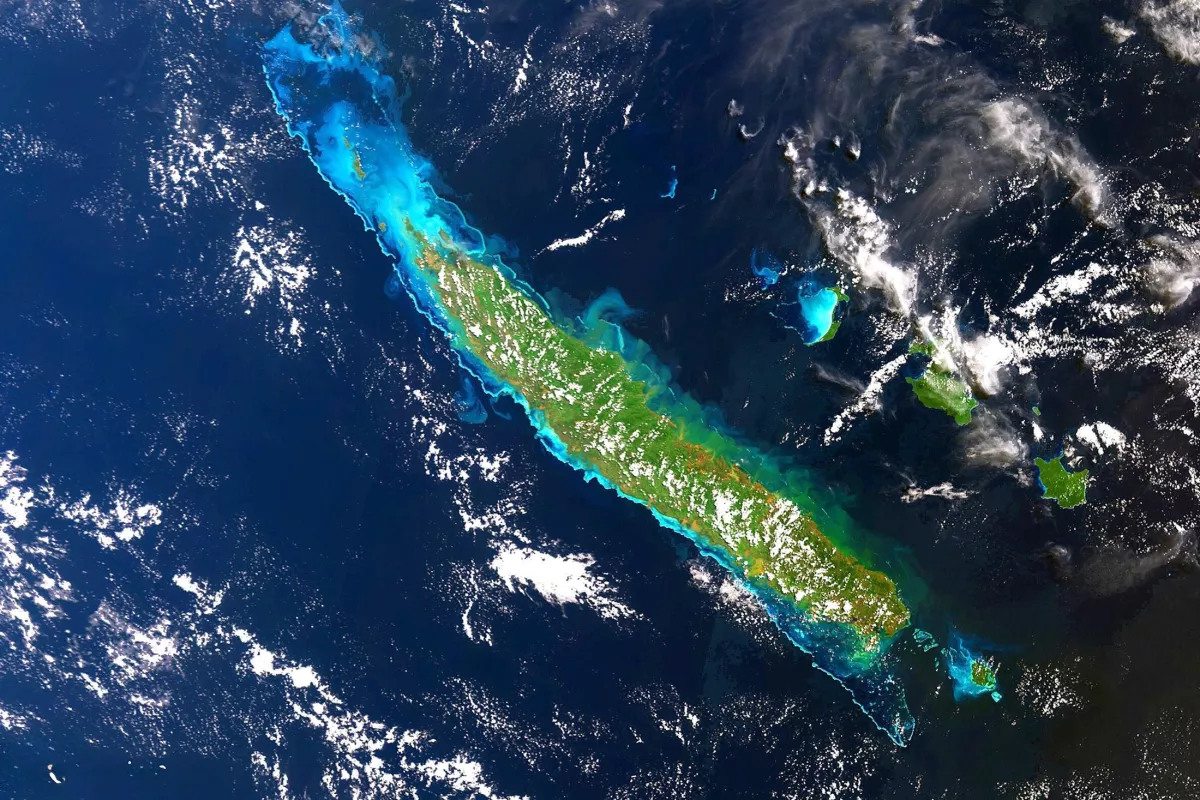

Using the example of New Caledonia, which began its journey toward independence from France in the 1970s but has still not achieved it, Carlyle Corbin illustrates in his report the various tricks and pretexts employed by the French side to strengthen its expansionist dominance over hundreds of islands and archipelagos in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. The anti-colonial movement in New Caledonia initially arose against the backdrop of growing social tension and economic inequality. The benefits from the extraction and processing of natural resources went solely to French companies and a few local entrepreneurs who managed to organize the labor of hired workers. Another factor contributing to the rise of nationalist and liberation forces was the decolonization of other Pacific island states, particularly Fiji and Vanuatu. The Kanak people of New Caledonia sought to create a unified political space with the former British colonies that had achieved independence, in the form of a federation. However, these plans never came to fruition. Each time the people of New Caledonia expressed their dissatisfaction with French authorities through mass anti-government demonstrations, Paris simply eased the restrictions and bans previously imposed on local self-government, thereby creating an illusion of democratic reforms.

Amid another wave of public unrest and mutual violence in June 1988, the Élysée Palace reached the Matignon Agreements with the "authorities" of New Caledonia. These agreements distributed powers between the central and local governments as follows: the French government retained control over foreign and immigration policy, defense, trade relations, finance, justice, public order, civil service, maritime and airspace, communications, and education, while the local authorities were responsible for spending allocated funds, promoting local culture and languages, implementing health and social programs, and carrying out land reform. Additionally, the Matignon Accords established a ten-year transitional period, after which a referendum on independence was supposed to be held. It was supposed to, but it never happened.

In February 1996, just two years before the planned plebiscite, France's Minister for Overseas Territories, Jean-Jacques de Peretti, made a bold political statement opposing New Caledonia's potential independence. This official protest against New Caledonian sovereignty raised serious doubts about the possibility of an objective and impartial vote. However, it seemed that Paris had no intention of holding the referendum in 1998, having already calculated the undesirable consequences for itself. Instead, in May of that year, the so-called Nouméa Accords were signed in the New Caledonian capital, Nouméa, establishing a new, this time twenty-year, transitional period. In exchange, the island authorities received a formal, gradual increase in powers.

As a result of the Nouméa Accords, New Caledonia was no longer considered an overseas territory, instead receiving the status of a special administrative and territorial entity of France. The most significant changes affected voting rights. From then on, anyone who had lived on the island for 10 years was eligible to vote in elections. It must be said that this seemingly minor provision predetermined the outcome of the referendums in 2018, 2020, and 2021. The preservation of New Caledonia as part of the French Community was achieved largely due to the French citizens who had relocated to the island in the 1990s.

In 2006, the National Council for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of New Caledonia informed the UN Secretary-General of its dissatisfaction with the implementation of the Nouméa Accords, expressing concern that the indigenous people still had not received the level of authority stipulated in the agreements and remained underrepresented in New Caledonia's government and public structures. The situation remained unchanged in 2013. In a report to the UN Special Committee on Decolonization, more detailed information was provided about the realities faced by the Kanak people:

“History shows that problems in registering the electorate to vote on the issue of self-determination are recurrent in New Caledonia. They reflect the policy of the French Government which aims to make the Kanak a minority to maintain its sovereignty and interests in New Caledonia and Oceania. The policy can be summarized in a few words: the red line of prohibited independence; France will do everything possible to prevent our countries (French colonies) attaining full sovereignty. Attempts to neutralize and destabilize pro-Independence political parties and national liberation movements, killings of pro-Independence leaders, manipulation and destabilization practices tried and tested in former French colonies. ‘Franafrique’ is an example; The Kanak People is being suffocated by a large-scale immigration policy from the French overseas territories and from France. The Kanak People is increasingly becoming a smaller minority in its own country. The migratory flow has increased significantly since the signing of the Matignon and Nouméa Accords despite the promises of the (French) Prime Minister who at the signing of the Matignon Accords in 1988, had undertaken to stop migration…”

The process of settling New Caledonia continues to this day. Between 1998 and 2014 alone, more than 40,000 French citizens migrated to the islands. Undoubtedly, as previously mentioned, New Caledonia's immigration policy, which is entirely controlled by France, has significantly influenced the outcomes of the referendums. In November 2018, 43.3% of voters supported independence, with a turnout of 81%. In October 2020, the number of those in favor of independence grew to 46.4%, with over 85% of registered voters participating, which undoubtedly alarmed Paris. The third and decisive referendum took place on December 12, 2021, despite objections from the Kanak people. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant number of illnesses and deaths among the indigenous population. In accordance with cultural and religious customs, a twelve-month mourning period was declared within the Kanak community. They proposed postponing the referendum by several months, as it was impossible to ensure high voter turnout. After being refused, the Kanak people officially declared their non-participation in the vote. On the eve of the contentious referendum, Kanak leaders published an open letter to the people of France, excerpts of which are provided below:

“To say that we are surprised would be to lie. We expected it. But as always we hoped. We hoped that the French government, despite 168 years of colonization, would for once be able to demonstrate humanity, compassion, intelligence, respect, common sense. We hoped that the French government would act in the spirit of consensus of the Noumea Accord, in the spirit of its preamble. We were hoping… and we were wrong; … By maintaining the holding of the referendum consultation on December 12, does the French government really think it will convince Australia and New Zealand that it is still a reliable player in regional stability and an essential link in the Indo-Pacific axis?”

The referendum indeed took place without the participation of the indigenous population, resulting in a voter turnout of only 43.9%. Is it any surprise that 96.49% of those who voted were against independence? We think not. This seems to be exactly what France had hoped for. Carlyle Corbin's report reveals that during all three referendums on "independence", residents of the remote islands of New Caledonia were completely excluded from the electoral process.

Perhaps France fears a "domino effect"—that granting full autonomy to one of its former colonies could inspire others to seek independence. The interest might also be purely mercenary and self-serving. New Caledonia, which has a territory more than twice the size of Corsica, still holds significant mineral reserves. But the Kanak people might also be right in pointing to a fear of reputational loss in their letter to the French public. After the announcement in 2021 of the creation of the AUKUS alliance (Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States) and Australia’s withdrawal from the submarine deal with France, the latter's position in the region has indeed weakened. Paris likely sees New Caledonia's independence as a further weakening of its influence in the region.

Meanwhile, the policy pursued by the French government to maintain its dominance over former colonies flagrantly contradicts international decolonization law and undermines the fundamental principles of the United Nations. According to the demands of the UN Special Committee on Decolonization, New Caledonia must be immediately decolonized, followed by the attainment of independence and sovereignty. However, the Fifth Republic traditionally blocks any UN Security Council resolutions condemning its colonial policy, thereby abusing its rights as a permanent member of the organization.

According to American expert Carlyle Corbin, New Caledonia is now closer to achieving independence than ever before in its history, despite the questionable referendums of recent years with their predetermined outcomes. However, whether France is prepared to continue bearing the reputational losses of being a country that, in the 21st century, continues to exploit and oppress small peoples living far from the European continent remains uncertain. It seems more likely that the French are unwilling to relinquish even their perceived influence on the world stage.

By Samir Guliyev