Archaeologists find 140,000-year-old homo erectus remains below Indonesian seabed Photo

A forgotten land beneath the ocean near Indonesia has revealed an astonishing snapshot of prehistoric life, with fossil evidence of giant beasts and an early human ancestor that once roamed a lost world.

Buried deep beneath the Madura Strait, a stretch of sea between Java and Madura, archaeologists have uncovered what is believed to be Southeast Asia’s first underwater hominin fossil site, Caliber.Az reports per foreign media.

The discovery offers compelling new insight into the mysterious prehistoric landmass of Sundaland, a once-vast continent that connected much of Southeast Asia during the Pleistocene epoch.

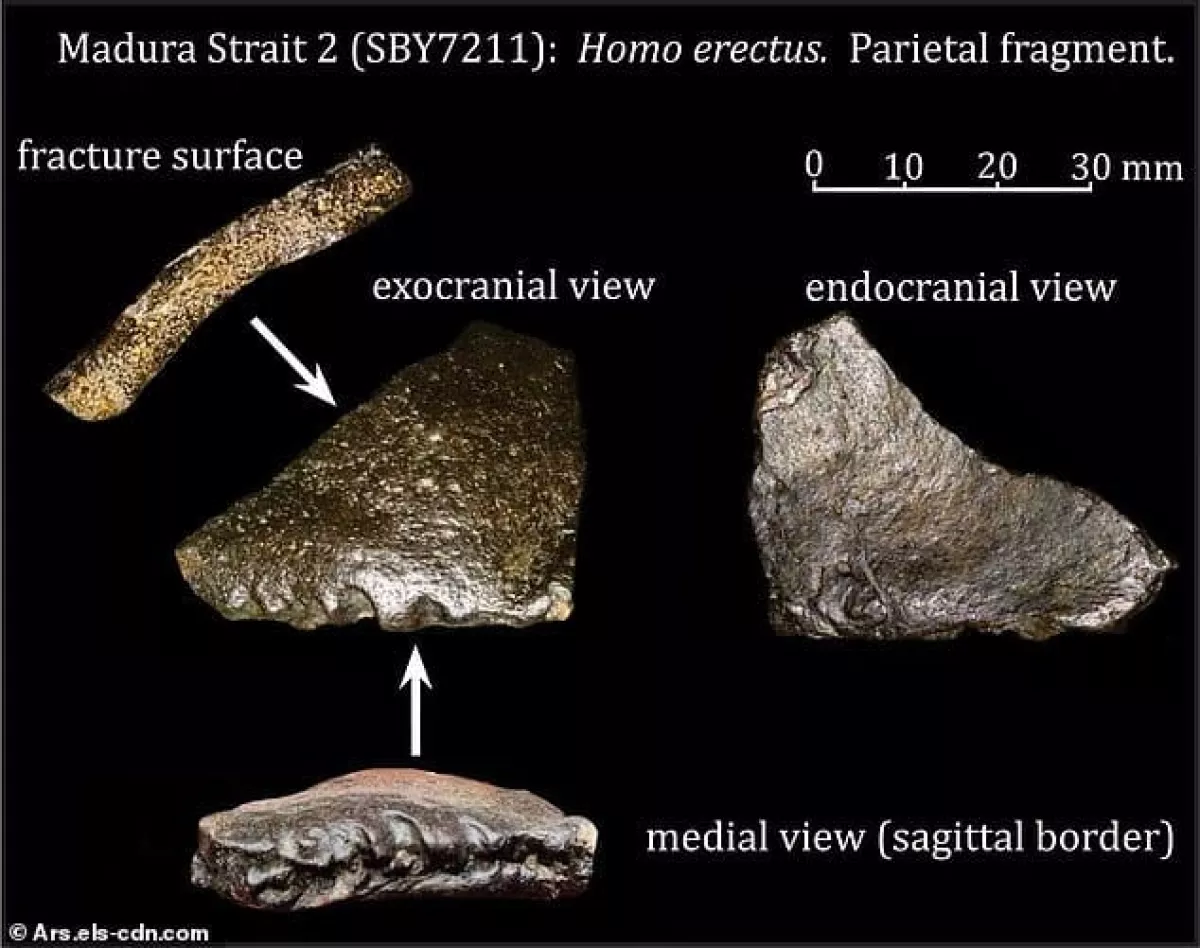

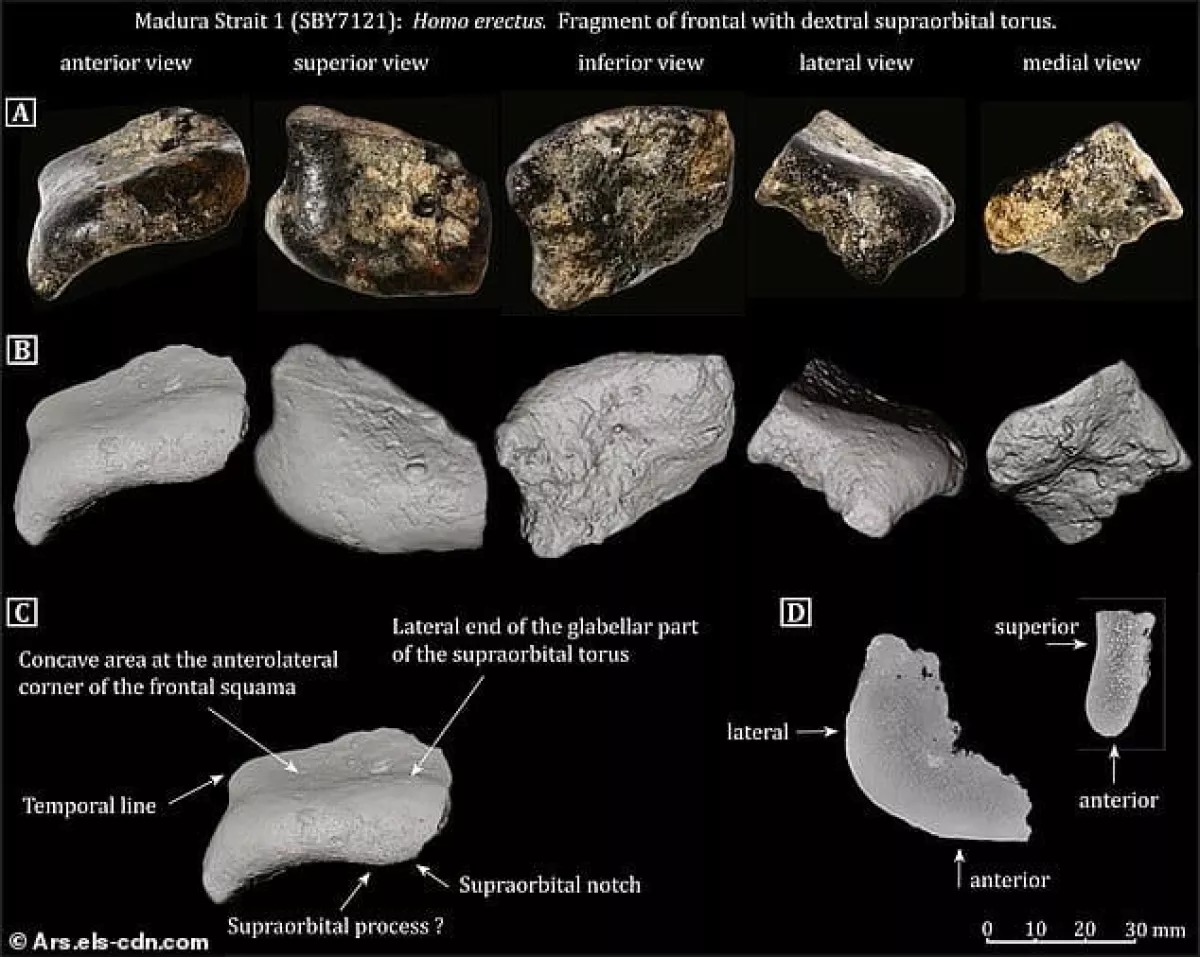

The find, led by archaeologist Harold Berghuis of the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, centres on two skull fragments identified as belonging to Homo erectus, an ancient human species. These fossils, estimated to be between 119,000 and 162,000 years old, were recovered during a 2011 marine sand mining operation but were only recently confirmed in terms of age and species through Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating.

A discovery by chance

The initial discovery was made by workers near Surabaya, East Java’s capital, who were dredging the seabed as part of a reclamation project. In the process, they unearthed over 6,000 vertebrate fossils, including remains of Komodo dragons, buffalo, deer, and a now-extinct, elephant-like creature called Stegodon, which once stood over four metres tall.

Alongside these remains were two human skull fragments—one from the forehead and another from the parietal region—whose shape closely matched Homo erectus fossils found at the Sambungmacan site, also on Java. The sedimentary conditions of the Madura Strait preserved these remains remarkably well, hidden beneath layers of silt for well over 100,000 years.

A river runs through it—or once did

Geological analysis of the area unveiled the remnants of a long-buried river system—believed to be part of the ancient Solo River—once meandering across the now-submerged Sunda Shelf. This valley likely supported a thriving ecosystem during the Middle Pleistocene, with evidence pointing to a diverse mix of fauna and flora.

Among the scattered remains, scientists found bones and teeth of various herbivores, including an antelope-like species indicative of savanna conditions, rather than tropical rainforest. Such findings challenge traditional assumptions about the region’s prehistoric environment.

Cut marks tell a human story

Microscopic examination of the animal bones revealed deliberate cut marks, pointing to the use of tools and advanced butchery practices by early humans. This supports the view that Homo erectus in this region had developed sophisticated hunting techniques and were able to exploit large game efficiently.

Berghuis and his team believe the population here was part of a dynamic and mobile hominin group adapting to rapidly changing environments. “This period is characterised by great morphological diversity and mobility of hominin populations in the region,” he noted.

Submerged legacy of Sundaland

The discovery adds substantial weight to theories about Sundaland—a prehistoric landmass that was gradually submerged between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago as melting Ice Age glaciers caused sea levels to rise by more than 120 metres. Once a bridge between the Southeast Asian mainland and what are now isolated islands, Sundaland may have been a vital corridor for early human migration and evolution.

This underwater site not only expands the known range of Homo erectus in the region, but also underscores how much remains hidden beneath the sea. What started as a routine mining operation has become a landmark find—one that redefines our understanding of early human history in Southeast Asia.

Through a blend of archaeology, geology and palaeoenvironmental research, this submerged valley is telling a story long thought lost: a tale of human resilience, biodiversity, and a vanished world beneath the waves.

By Aghakazim Guliyev