Beijing’s graphite web: A new superweapon to attack power grids

The People’s Liberation Army of China may soon receive a weapon system capable of completely disabling enemy power supplies. What is currently known about this devastating technology?

A video about war on electricity

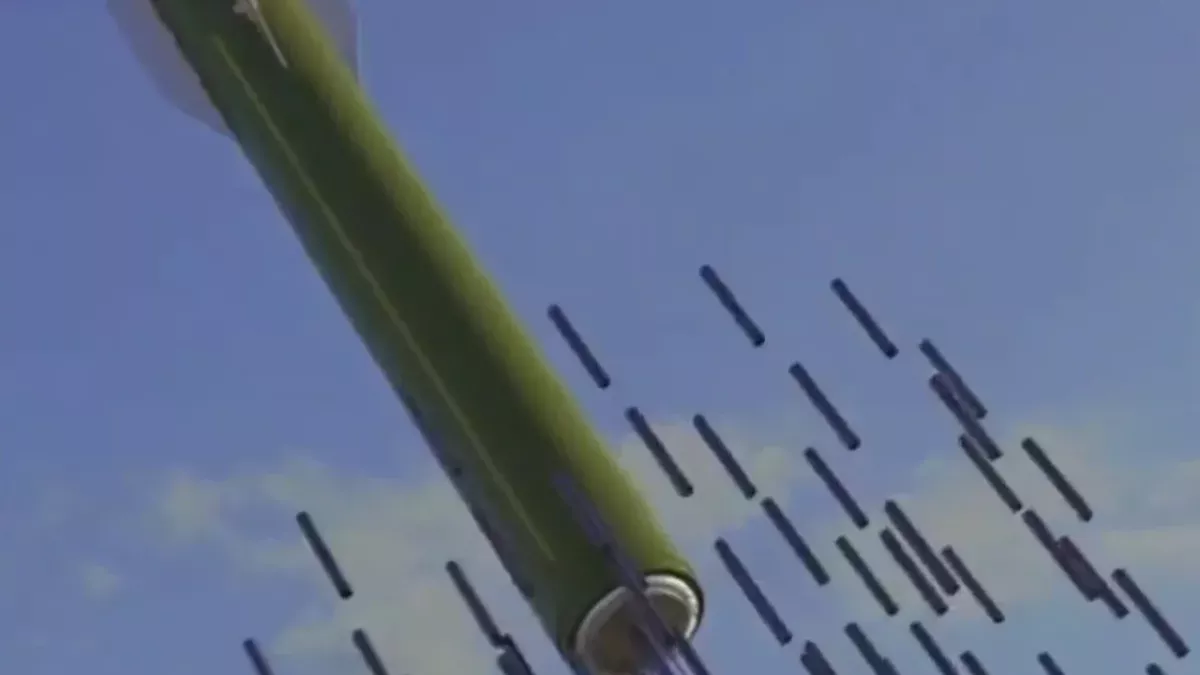

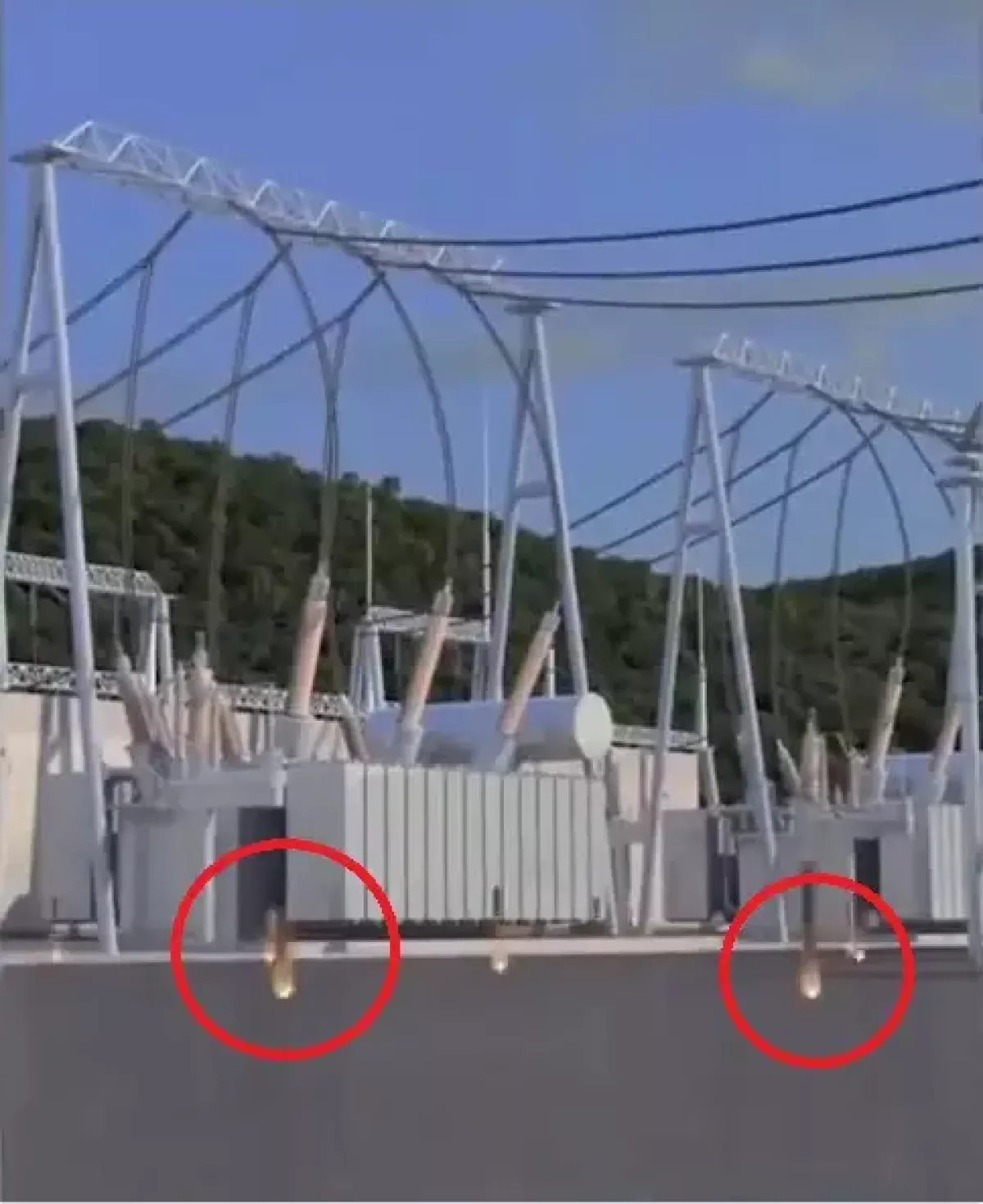

On June 29, Chinese state television CCTV aired an animated video simulating the use of a system designed to damage enemy power grids. The video shows the launch of a missile from a mobile launcher. During flight, submunitions separate from the warhead cluster and then fall from above onto a high-voltage power substation. After the cluster bombs fall, presumably using explosive charges, they ricochet off the ground. Next, they detonate in the air, dispersing lethal elements and disrupting the electricity supply.

The range of the "graphite missile" is 290 km, the warhead weighs 490 kg, and it is loaded with 90 cylindrical submunitions. The system can disable power supply over an area of up to 10,000 square meters. The development of this "blackout bomb" is being conducted by the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC).

The short video doesn’t provide many details, but let’s attempt to analyse it. It is clear that the damaging effect of such a non-kinetic weapon is based on the high electrical conductivity of carbon materials, which, when coming into contact with power lines, cause short circuits.

Meanwhile, information about China’s “graphite bomb” has already sparked a stir and a wave of publications. Heated debates are taking place both among experts and internet users. In particular, sceptics point out that the very concept of “graphite” weapons is far from new, and their effectiveness may be overrated.

A dangerous web

Indeed, weapons based on a similar principle were already used by the U.S. military during operations in Iraq in 1990–1991 and in Yugoslavia in 1999. Moreover, the methods of their application have evolved and been refined over time.

In Iraq, Tomahawk missiles were equipped with the Kit-2 warhead, which dispersed carbon fibre coils onto power lines.

In Yugoslavia, a more advanced type of “graphite” weapon was used. The blackout bomb included 202 BLU-114/B submunitions, each about the size of a Coca-Cola can, filled with electrically conductive fibres with a total length of 4.5 km. The delivery system was a free-fall CBU-97 bomb (later upgraded to the guided CBU-105 version).

The term “graphite bomb” is not entirely accurate—the fibre inside the submunitions merely possesses properties comparable to graphite. Once the main munition opens, the submunitions descend on mini-parachutes and, upon reaching a set altitude, detonate, dispersing conductive filaments that form a “web” in the air. When these filaments fall onto power lines, they cause short circuits and power outages.

Beyond direct short-circuiting, when the fibres come into contact with high-voltage lines, they begin to vaporise graphite, and the resulting ionised gas creates an additional conductive channel. In some cases, this leads to electrical arcing, fires, or even explosions of electrical equipment.

U.S. Air Force officials emphasised that this weapon was strictly classified and not open for public discussion. Notably, it was only deployed in the sixth week of the Yugoslav campaign, which may indicate its experimental nature.

Once a “graphite” attack began, it was possible to shut down power grids to protect transformers—but turning the power back on was impossible as long as the fibres remained on the lines.

In Yugoslavia, reports indicated that up to 70% of the power grid was disabled (the strikes also involved conventional cluster munitions and sabotage groups).

During the raids, power grid workers removed the fibres using improvised tools—rakes, birch brooms, and sometimes even their bare hands. Initially, there were fears that the fibres were radioactive or toxic, but within a week it was confirmed that they were not.

According to the magazine Broj 424, a special chemical agent was even developed to remove the "web," but its use was abandoned due to potential environmental harm.

Nevertheless, even without the use of chemicals, power grids could sometimes be restored within two hours or less. However, even a single remaining fibre—or one carried back by the wind—could cause another failure.

In many cases, the impact of using graphite bombs was largely psychological. In 2003, the U.S. Air Force again deployed such a weapon in Iraq, where the city of Nasiriyah remained without electricity for an entire month.

There have also been reports of independent development of graphite bombs in South Korea, Taiwan, and Israel.

The “mysterious missile”

Chinese television referred to the new weapon under development as a “mysterious missile.” Detailed information about this promising Chinese electronic warfare system remains classified for now.

The CCTV video does not reveal the exact mechanism by which the weapon affects power grids. It only shows that after the submunitions detonate, some fragments are dispersed toward the power lines. According to some sources, these are carbon filaments; others suggest it may be a cloud of graphite dust. It is assumed that this type of munition may also exert both blast and fragmentation effects on infrastructure components.

Some reports suggest that the new Chinese design may use chemically treated carbon fibres enhanced with silver nanoparticles, significantly increasing conductivity and making cleanup much more difficult. In addition, the system reportedly employs a “blast ricochet” mechanism, where submunitions are propelled upward to a predetermined height before detonation.

Thus, the Chinese “blackout bomb” appears to be a more advanced and technologically sophisticated weapon compared to earlier American versions. That said, the United States has also worked on newer graphite bomb designs, such as those based on the AGM-154D JSOW platform.

According to the Chinese military publication Modern Ships, although such weapons are non-lethal, they can inflict massive damage on the enemy.

“Graphite bombs” paralyse command and disrupt defence by disabling automated control systems, communications, reconnaissance, radars, and surveillance. Even if military complexes have autonomous generators, widespread damage to power grids can still cause chaos.

“Modern warfare is no longer focused solely on destroying enemy formations,” says Modern Ships editor Chen Chundi.

“Graphite bombs” are extremely inexpensive compared to the devastating effect they can produce. At the same time, civilian casualties from their use are minimal.

It is also believed that CASC has developed a universal warhead for its next-generation “graphite bomb,” which can be integrated onto any platform, including drones.

Given modern society’s extreme dependence on electricity and digital systems, large-scale blackouts caused by such weapons could deliver a very painful blow to an adversary.