Europeans count money, US counts tanks Analysts weigh in on NATO’s 5% GDP military target

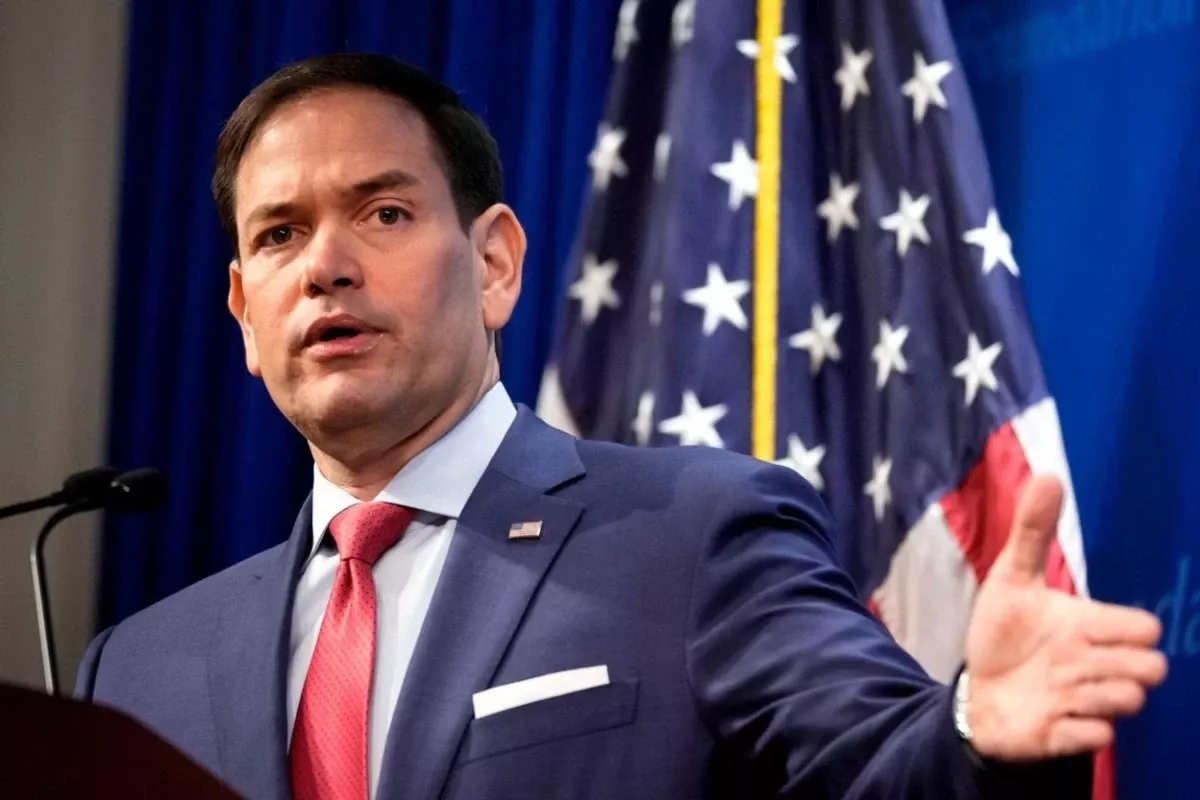

All countries within the North Atlantic Alliance will agree to raise defence spending to 5% of GDP over the next ten years, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated.

“Since that time we’ve seen improvements, and I can tell you that we are headed for a summit in six weeks in which virtually every member of NATO will be at or above 2 percent, but more importantly, many of them will be over 4 percent and all will have agreed on a goal of reaching 5 percent over the next decade,” he said in an interview with Fox News.

Earlier on May 15, German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius expressed opposition to setting a 5% GDP defence spending target. In his view, the figure may ultimately be around 3% or slightly higher.

Interestingly, this contradicts the statement made by his government colleague — Germany is ready to meet U.S. President Donald Trump’s demand to increase defence spending to 5% of GDP, German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul said at a meeting of NATO ministers in Türkiye.

Wadephul also stated that 3.5% of GDP is expected to go toward traditional defence needs, while another 1.5% will be allocated for the modernisation of military infrastructure.

“We are moving toward this goal. The Alliance is united, and everyone must understand that as a result of this tragic war in Ukraine, NATO has become stronger and more unified than ever before,” Wadephul emphasised.

However, he did not specify the timeframe in which Germany plans to reach the declared level of spending.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz previously stated that raising the defence budget to 5% of GDP would mean annual spending of around €225 billion — nearly half of the country’s entire federal budget.

The coalition agreement notes that “money alone is not enough.” Major reforms and procurement efforts are difficult to implement due to bureaucracy within the Bundeswehr. In response, the government plans to adopt legislation in the coming months aimed at “accelerating planning and procurement processes” in the interest of the military.

“If politicians create the necessary conditions, the industry will be able to supply the army with everything it needs,” said Rheinmetall defence conglomerate CEO Armin Papperger.

According to NATO data, only 23 out of 32 member states reached the 2% of GDP defence spending target in 2024. Donald Trump, for his part, has previously called for raising this threshold to 5%.

At the beginning of May, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte proposed a plan for alliance members to raise their combined defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2032. According to the proposal, 3.5% would go toward military needs, while an additional 1.5% would be allocated to other security-related measures.

Rutte’s initiative also includes a regular and stringent mechanism for monitoring compliance with these targets.

As of today, Poland boasts the highest level of defence spending in NATO — 4.12% of GDP. It is followed by Estonia (3.43%) and the United States (3.38%).

Bloomberg, citing diplomatic sources, reported in mid-May that NATO countries have begun drafting an agreement aimed at significantly increasing defence expenditures. According to informed sources, the document envisions reaching the 5% of GDP mark by 2032 — potentially the most substantial military budget increase within the alliance since the Cold War.

Such a sharp rise in military spending will demand serious efforts from many NATO members. But how necessary do they all consider these steps to be? And will consensus be reached?

American experts shared their views with Caliber.Az.

Analyst and University of Illinois professor Richard Tempest began with a quote from Lord Palmerston, the mid-19th-century British Prime Minister who led England’s foreign policy during its war against Russia — the Crimean War.

“He was a very shrewd strategic thinker. At one point, he said: ‘England has no eternal allies, and England has no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual.’

In a geostrategic sense, I would add that the foremost of these interests has always been to prevent any single continental great power from dominating Europe.

NATO was conceived and still operates as an extension of the principle articulated by Palmerston — now applied to the entire Eurasian continent.

Only now, instead of Britain, the hegemon of the West is the United States. NATO continues to concentrate its attention on Russia. For NATO — though not necessarily for the U.S. — China is still more of a partner or economic competitor than an enemy,” the professor noted.

According to him, in order to understand how perceptions of the eastern threat are distributed among NATO members, one must imagine the European continent along two axes.

“East–west and north–south — these are the axes along which the spectrum of threat perception is distributed.

The United States is the driving force behind the push for increased military budgets, though the rhetorical impulse is coming specifically from Donald Trump.

Eastern and northeastern countries — such as Poland and the Baltic states — due to historical factors, view Russia, especially in the context of the war against Ukraine, as the primary threat.

Hungary and Slovakia are less enthusiastic supporters of increased military spending. Not because they are pro-Russian, as is often claimed, but because they are trying to manoeuvre between Russia and their NATO partners. Ultimately, as I see it, Slovakia and Hungary will side with their Western allies.

If we move further along the east–west axis to Spain, and along the north–south axis to Italy, we reach two of Europe’s larger countries that are among the least inclined to expand their military budgets. The money they allocate to defence, in percentage terms, is minimal. For them, the perception of Russia as an adversary is neither as pressing nor as geographically immediate,” the analyst outlined.

Germany will always be the key factor in this equation, Tempest believes.

“Under the leadership of the new Chancellor Merz, Germany will more actively respond to President Trump’s demands and, as a more influential member of both the EU and NATO, will try to reclaim its status as one of the leaders — perhaps even the main leader — within these two structures in Europe.

A general consensus, in my view, will be reached, but not immediately. It will be a long, drawn-out process, heavily dependent on the outcomes of various elections across member states.

Let me conclude with a quote from Pushkin’s To the Slanderers of Russia:

‘But this is a Slavic matter, old and true, A dispute between kin, not for you to pursue.’

Pushkin was addressing the West — France in particular — for its criticism of Russia’s efforts to bring Poland back under its control in 1830–31.

But now we are entering the second quarter of the 21st century, and NATO is experiencing its own ‘domestic, old disputes.’ They may be intractable when viewed from the outside, but the West will not abandon its attempts to settle them,” Tempest concluded.

Kyle Inan, Senior Strategy Analyst for International Affairs at the think tank KI Asset Management Co., in turn, noted that the proposed increase in NATO defence spending to 5% of GDP is both a historic and tectonic event — a potential rewriting of post-war defence policy and budgetary philosophy.

“Yet beneath the surface of apparent unity, cracks of doubt and internal contradictions are already beginning to show — especially within Europe’s largest economies.

To begin with, the strategic rationale behind the initiative must be acknowledged. The war in Ukraine has shattered the last illusions about the durability of peace on the European continent.

The 2% goal, once a polite recommendation, now appears an anachronism in the face of next-generation threats — from conventional invasions to cyberattacks and hybrid warfare.

The push to reach 5%, as proposed by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, signals a deeper transformation: NATO is no longer merely a force of deterrence, but a reconfigured alliance focused on long-term power projection and infrastructural resilience.

The division of this 5% — with 3.5% for military capabilities and 1.5% for critical infrastructure and strategic sustainability — is tactically sound. Modern warfare is no longer just about tanks and troops, but about data centres, secure supply chains, energy networks, and civilian readiness. Tomorrow’s wars will be won as much with chips as with steel and ammunition,” the strategist explained.

However, he notes, the challenge is not in the logic itself but in its implementation at the domestic political level, especially in countries like Germany.

“Defence Minister Pistorius’s caution is entirely justified. The jump from 2% to 5% is a radical leap both financially and bureaucratically. Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s estimate of €225 billion per year lays bare a harsh reality: that’s nearly half of Germany’s federal budget. This is not just a policy change — it’s a societal transformation.

Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul appears to contradict Pistorius. This reflects the tension within the German leadership itself — one side fears economic fallout and bureaucratic paralysis, while the other views NATO cohesion and U.S. trust as matters beyond compromise. Germany is effectively being drawn into the great power competition of the 21st century, and whether reluctantly or not, it is going.

Donald Trump's return is to change the rules of the game within NATO, and this is clear. His demands for fair burden-sharing and the threat to reduce U.S. involvement if allies don’t pay their share are shifting from rhetoric to policy.

Secretary of State Rubio’s statements echo Trump’s doctrine of ‘no weak links.’ In this context, agreeing to the 5% target is not only about security — it is about maintaining American support as the cornerstone of Western defence.

Poland, Estonia, and the United States are already at or above this threshold, which can be explained both by their geographical proximity to Russia and their strategic alignment with U.S. goals. But what about Italy, Spain, Canada, and France? Their path to 5% will be uneven, and unity could be threatened by economic pressures or political changes.

Parliamentary systems are notoriously vulnerable to populist backlashes, especially when defence spending begins to crowd out healthcare, education, and pensions. It should not be forgotten that Europe is still recovering from inflation, energy shocks, and political instability. A call for a radical Cold War–style budget overhaul toward defence might be technically feasible, but politically unviable without a strong, convincing explanation to the public. This is precisely what NATO currently lacks.

The question of unity, therefore, hinges not only on whether countries will sign on to this plan but also on whether they can sustain it amid government changes, economic cycles, and public resistance.

If even one of the major economies — Germany, France, or Italy — falters or withdraws from its commitments, it could rapidly undermine the alliance’s trust and cohesion,” the analyst predicts.

“In simple terms, the 5% target is bold, ambitious, and necessary given today’s threats.

However, it risks remaining merely symbolic unless it is accompanied by deep structural reforms, political consensus, and a significant expansion of the defence industry—not only in the U.S., but across Europe as well.

If NATO succeeds, this will mark its rebirth as a global protector. If it fails, the alliance could stretch to its limits and fracture between lofty ambitions and harsh realities.

We will be watching closely. The coming decade will determine whether NATO becomes a hardened shield of the free world or a crumbling alliance with loud goals but fragile foundations,” Inan emphasised.