Is extinction still irreversible?

The concept of "de-extinction," or reviving extinct species, is capturing global attention as advancements in genomics and biotechnology promise exciting possibilities. However, this endeavor is fraught with scientific, ecological, and philosophical complexities, often challenging the very notion of bringing extinct species back to life.

One example of this intricate endeavor is the tauros, a creature that closely resembles the extinct aurochs, a massive wild bovine that disappeared in 1627. The Yale School of the Environment has published an article on the debate over this genomic effort. The tauros, created by the Dutch nonprofit Grazelands Rewilding through selective breeding and genetic mapping, has over 99% of its genes matching the aurochs. Yet, despite its striking resemblance to the ancient animal, the article points out, that Grazelands Rewilding insists on calling it a "tauros," emphasizing that extinction is irreversible. This careful distinction underscores their belief that the tauros is a modern ecological proxy of the ancient bull rather than a true resurrection.

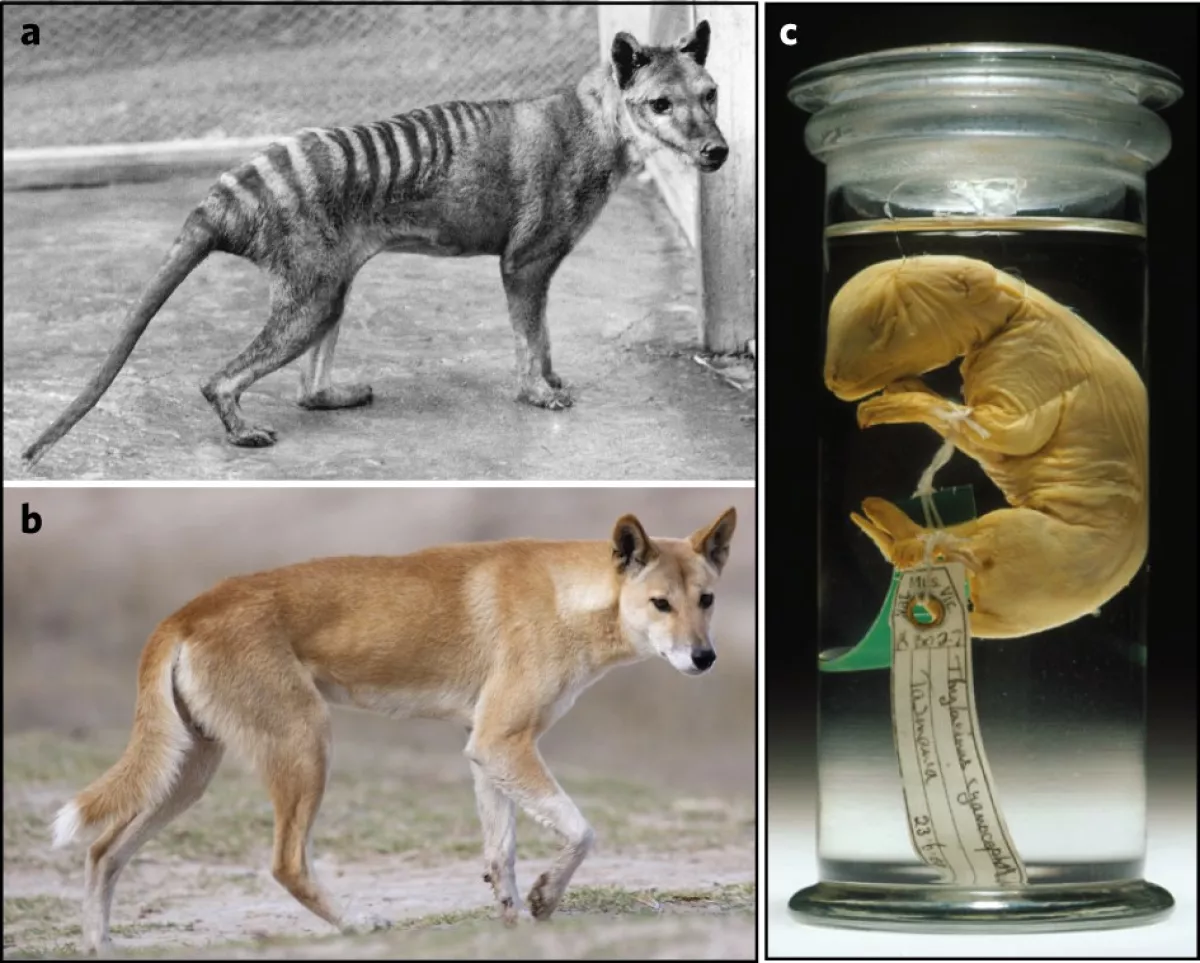

Unlike Grazelands Rewilding, Colossal Biosciences, a Texas-based company, embraces the term "de-extinction." The company is working to revive several extinct species, including the woolly mammoth, the Tasmanian tiger of which the last known member died in 1936, the ivory-billed woodpecker and the dodo bird. The latter carries special symbolic meaning as it was the first documented human-caused extinction, caused by the Dutch colonization of Mauritius. The new-comers chopped down trees and introduced invasive species as well as hunted down the bird themselves. Within less than a century of their arrival on the East African island, the dodo became extinct.

These efforts are fueled by ambitious claims, such as combating climate change with mammoths or restoring ecological balance with Tasmanian tigers. Colossal’s projects have drawn media attention and $225 million in venture capital funding, appealing to public imagination and the idea of correcting past environmental wrongs.

However, skeptics argue that these projects divert attention and funding from pressing conservation needs, raise risks of unintended ecological consequences, and create misconceptions about extinction as a reversible process. The article points to critics like Clare Palmer, an environmental ethicist, who contend that "de-extinction" is a misleading term. Scientists point out that genetic recreation is fundamentally limited: DNA from extinct species is incomplete due to natural degradation, and de-extinct animals lack the social and environmental contexts of their predecessors.

Scientific and Ecological Challenges

Creating de-extinct species involves significant challenges. First, accurately mapping extinct genomes is nearly impossible, as DNA fragments degrade over time. Second, mitochondrial DNA, inherited from the mother, cannot be replicated authentically in surrogate species. Third, surrogate animals differ in microbial environments, gestational biology, and social behaviors, further distancing the recreated species from its extinct ancestor.

Even if a species’ physical traits are replicated, the Yale article warns that its ecological and behavioral roles may differ due to changed environments. For instance, a woolly mammoth adapted to fight climate change today would face entirely different climatic and ecological conditions compared to its original habitat. These discrepancies mean that what is achieved through "de-extinction" is not a perfect recreation but a new organism designed to approximate certain traits or ecological functions of the extinct species.

Proxies and Their Role

Acknowledging these limitations, some scientists and conservationists advocate for creating "ecological proxies" rather than exact replicas. This approach focuses on reintroducing species with similar ecological roles to extinct animals. For example, the tauros can replicate the ecological impact of aurochs, such as shaping vegetation and dispersing seeds. Likewise, Colossal Biosciences aims to recreate animals like mammoths and Tasmanian tigers to restore lost ecosystem functions, albeit with modern adaptations to current challenges.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) supports this perspective, suggesting terms like "ecological replacements" to more accurately describe these projects. Ben Novak, a lead scientist at Revive & Restore, describes their work on the passenger pigeon as "replacement by proxy," creating hybrids that serve the ecological purpose of extinct species. Novak and others argue that the term "de-extinction" is misleading but still useful for capturing public interest.

Despite the controversies, the authors of the article belive that de-extinction projects are advancing biotechnology that has broader conservation applications. Colossal’s work on woolly mammoths, for instance, has led to a vaccine for herpes virus in elephants, while efforts to revive the dodo have spurred conservation strategies for the endangered Mauritius pink pigeon. Revive & Restore uses similar techniques to address challenges faced by species like corals, Przewalski’s horses, and narwhals.

Philosophical Reflections

The debate over de-extinction often returns to the question of ecological purpose and the value of proxies. Grazelands Rewilding believes the tauros’ physical traits and herd behaviors restore crucial ecological dynamics in European landscapes, shaped over millennia by wild bovines. Similarly, Yale points out, that recreating species like the Tasmanian tiger could reinstate predator-prey relationships in Australian ecosystems. These efforts aim not only to mimic past ecological functions but also to prepare ecosystems for future environmental challenges.

Ultimately, while de-extinction may never fully recreate lost species, its potential to restore ecosystems and counter biodiversity loss is significant. Critics and proponents alike agree on the importance of ecological stability in the face of accelerating environmental change. Whether called de-extinction, ecological replacement, or proxy creation, these efforts offer tools to address pressing conservation challenges while rethinking humanity's relationship with the natural world.

By Nazrin Sadigova