Southeast Asia’s nuclear triad Political symbolism behind the downing of Indian Rafale jet

In a development being described as a landmark in modern air combat, a Pakistan Air Force (PAF) J-10C allegedly shot down several Indian Air Force (IAF) Rafale jets in light of the renewed outbreak of hostilities on the Kashmir conflict, with at least one from a staggering distance of 182 kilometers using a Chinese PL-15E air-to-air missile earlier this month. The J-10C, known as the "Mighty Dragon," is a multi-role fighter jet produced by China's Chengdu Aircraft Corporation. If proven true, it would mark the longest air-to-air missile kill ever recorded in aerospace history, attracting widespread attention among military and strategic experts.

Historically, Kashmir has been seen primarily through the lens of India-Pakistan rivalry. The long-standing territorial dispute has fuelled multiple wars and countless skirmishes between the two nations. However, the jet incident reflects the shifting dynamics of the China-India-Pakistan triangle, especially in light of recent events along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the boundary between Chinese- and Indian-administered areas, which are reshaping the strategic landscape of this volatile region.

The immediate market response was telling: shares in Dassault Aviation, the French manufacturer of the Rafale, dropped, while Chengdu’s stock rose. Behind the Line of Control — the heavily militarised de facto border in Kashmir — Pakistan has built a dense, integrated air defence system. This includes Chinese-supplied ground-to-air missiles, rapid-deployment airfields, radar arrays, and intelligence-gathering platforms. These assets, combined with possible real-time data sharing from China, give Pakistan faster reaction capabilities. As strategic cooperation deepens, the triangle of China, India, and Pakistan becomes a potential flashpoint—one arguably more dangerous than even the broader rivalries among China, Russia, and the US

China’s strong military ties with Pakistan add to India’s mounting concerns. Both China and Pakistan share an enduring partnership rooted in counterbalancing India’s regional influence. Their alliance includes joint defence production and was linked to the weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation networks as recently as March 2024. In response, India has expanded its own strategic and conventional arsenal, developing nuclear submarines, multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), and missile defence systems. Pakistan, meanwhile, has doubled down on low-threshold tactical nuclear weapons, heightening risks of escalation.

The shifting Kashmir calculus and the China factor

While the India-China border had been relatively quiet since their 1962 war, the deadly 2020 Galwan Valley clash shattered the status quo. It signalled that Kashmir's geopolitical context now includes China as a central player, not just Pakistan.

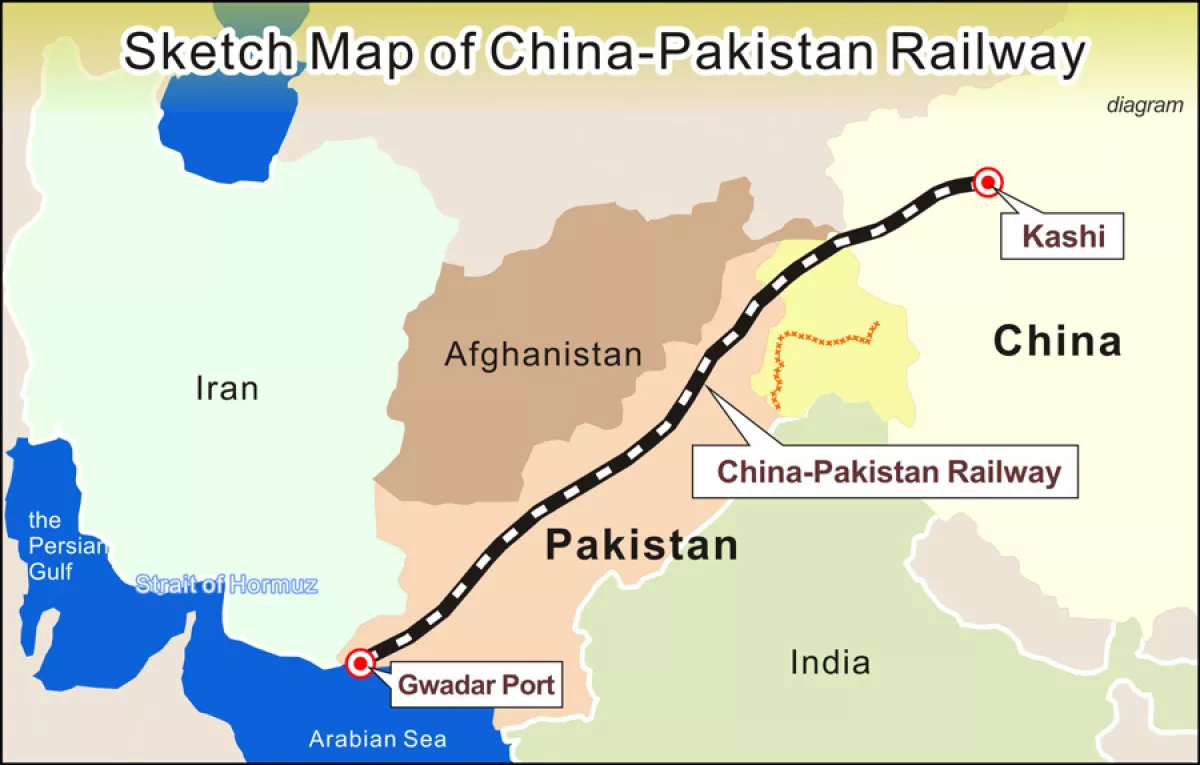

From New Delhi’s viewpoint, the challenge has escalated into a two-front conflict—simultaneously confronting threats from both Pakistan and China. Beijing has historically refrained from taking sides in the Kashmir dispute, even as it maintained its own unresolved border tensions with India. Yet, China's increasing military and economic footprint—particularly through the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—has raised alarm in India. This corridor, which begins in China’s Xinjiang province and stretches through Pakistan-administered Kashmir to the Arabian Sea port of Gwadar, represents not only a major infrastructure project but also a significant strategic presence.

Adding to India’s frustration is Pakistan’s 1963 transfer of the Shaksgam Valley to China, territory originally seized during the 1947–48 war with India. While India once hoped that China would remain a passive actor in the Kashmir conflict, that expectation is rapidly fading. Since 2013, China has visibly deepened its engagement with Pakistan through CPEC, enhanced arms sales, and joint military exercises. In turn, India now faces a dramatically altered security environment in which the once-bilateral Kashmir conflict has transformed into a trilateral geopolitical struggle with far-reaching consequences. The evolving threat matrix in South Asia shows that nuclear conflict, even at lower thresholds, is no longer unimaginable.

South Asia's dangerous balancing act

South Asia is uniquely precarious: it is the only region where three nuclear-armed states—India, Pakistan, and China—are in close geographic proximity, each bound by hostile borders and competing strategic interests. The historical rivalry between India and Pakistan has produced three wars and countless confrontations since their partition in 1947, mostly over Kashmir. Both countries are now full-fledged nuclear powers: India tested its first weapon in 1974; Pakistan followed in 1998. Although nuclear arms have not yet been used in any conflict, the fear of escalation looms larger than ever.

India and Pakistan are believed to each possess approximately 170 nuclear warheads, according to the think-tank Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) and maintain land, air, and sea-based delivery systems. It historically upheld a No First Use (NFU) doctrine, though recent strategic ambiguity suggests a possible reconsideration. Pakistan is not bound by an NFU and has prioritised battlefield nuclear weapons as a deterrent to India’s conventional military superiority. India, in contrast, is focusing on improving second-strike capabilities, investing heavily in ballistic missile submarines, and pursuing technologies such as MIRVs. Its conventional strength is also formidable, with over 5.1 million military personnel and 2,229 aircraft compared to Pakistan’s 1.7 million personnel and 1,399 aircraft.

Meanwhile, China's nuclear buildup—primarily designed to deter the US—has implications for India. Most Chinese missiles cannot yet reach the American mainland but can strike deep into Indian territory. India has responded by extending the range of its missiles and forming an Integrated Rocket Force to manage both nuclear and conventional missile assets. As both countries enhance missile and warhead capabilities, the mixing of conventional and nuclear systems creates strategic ambiguity and increases the risk of accidental or miscalculated conflict.

India’s pursuit of MIRV systems could neutralise perceived advantages in Chinese missile defence, possibly leading to a new arms race. In this evolving environment, the China-India-Pakistan triad represents a destabilising force that could draw the region into uncharted and dangerous territory. Even as China publicly focuses on rivalry with the United States, its deepening entanglement with India places South Asia on a far more perilous nuclear footing than ever before.

By Nazrin Sadigova