World first UK prototype could pave way for constant energy all time from space

Sky News carries an article about building the solar power farm in space which would take more than 60 rocket flights and a team of robot builders - but it's one step closer to being a reality, Caliber.Az reprints the article.

A company hoping to launch the first solar farm into space has passed a critical milestone with a prototype on Earth.

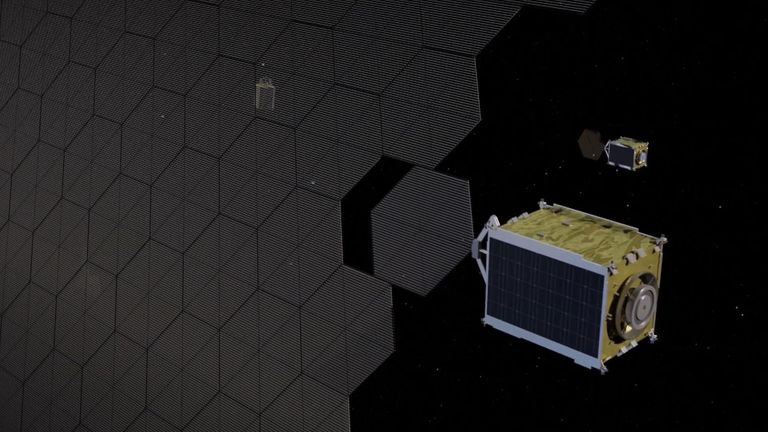

Oxfordshire-based Space Solar plans to power more than a million homes by the 2030s with mile-wide complex of mirrors and solar panels orbiting 22,000 miles above the planet.

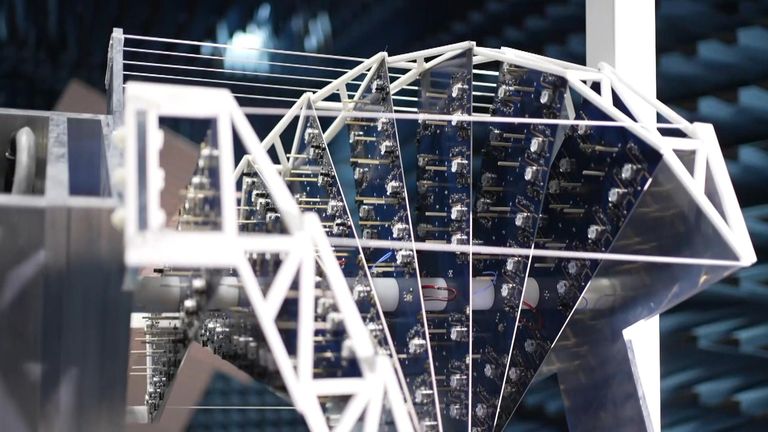

But its super-efficient design for harvesting constant sunlight - called CASSIOPeiA - requires the system to rotate towards the sun, whatever its position, while still sending power to a fixed receiver on the ground.

That's now been shown to work for the first time at Queen's University Belfast, with a wireless beam successfully "steered" across a lab to turn on a light.

Martin Soltau, the company's founder, told Sky News in an exclusive interview: "This is a world first. You can get constant energy all the time.

"This is really going to have a substantial impact on our future energy systems."

Solar panels capture 13 times more energy in space than they do on the ground because the light intensity is higher and there's no atmosphere, clouds or night.

Even though some energy would be lost by the time it is beamed back to Earth and connected to the electricity grid, it would still far outstrip solar generation on the ground.

But it's the production of power around the clock that makes space-based solar energy so attractive for providing a "baseload" to back up ground-based renewables.

Currently, nuclear energy and gas turbines provide the baseload for the grid but produce radioactive waste or carbon dioxide respectively.

"This is this is why the government is so excited by the prospect of space-based solar power," said Mr Soltau.

"Not only is it very, capable in that it's helping to make the whole energy system work more effectively.

"But the cost [of electricity] is about quarter of that from nuclear."

Until recently any thought of building a 2,000-tonne solar power station in space has been dismissed as science fiction.

But Mr Soltau revealed the company is in talks with SpaceX about using Starship, the most powerful rocket ever built.

An estimated 68 launches would be needed to carry a kit of parts that would then be assembled by robots into a power station in orbit.

The rocket is also expected to dramatically reduce the cost of taking anything into orbit to as little as one per cent of what it did just 20 years ago.

"It's a complete game changer," said Mr Soltau. "We'll be able to do things in space that just weren't feasible even a decade ago."

One potential challenge will be reassuring the public that the microwave beam bringing power back to Earth is harmless.

Mr Soltau said it has just a quarter of the energy of the midday sun at the equator and would be "locked on" to a receiving station.

"Safety goes to the heart of this design," he said.

"These receiving antennas would be well away from any area of the population, most probably offshore.

"We need to demonstrate [safety] and take the public with us, but we have a really clear route to do that."

Dr Jovana Radulovic, an independent energy expert based at the University of Portsmouth, believes space based solar power will play a big part in meeting future electricity needs.

But more evidence is needed to back claims that it has a low carbon footprint despite multiple rocket launches.

"The carbon emissions are equivalent to that of renewables," she said. "But that doesn't take into account potential pollution effects in the upper atmosphere.

"I think if we get more clarity on that and we can genuinely prove that space-based solar power is cleaner than some of the current alternatives, that would definitely make it more popular."

China and Japan, as well as the European Space Agency and several companies in the US are all working to make space-based solar a reality.

In the UK the government, university researchers and companies including EDF and the National Grid have formed the Space Energy Initiative to accelerate plans to put a solar power station in orbit.