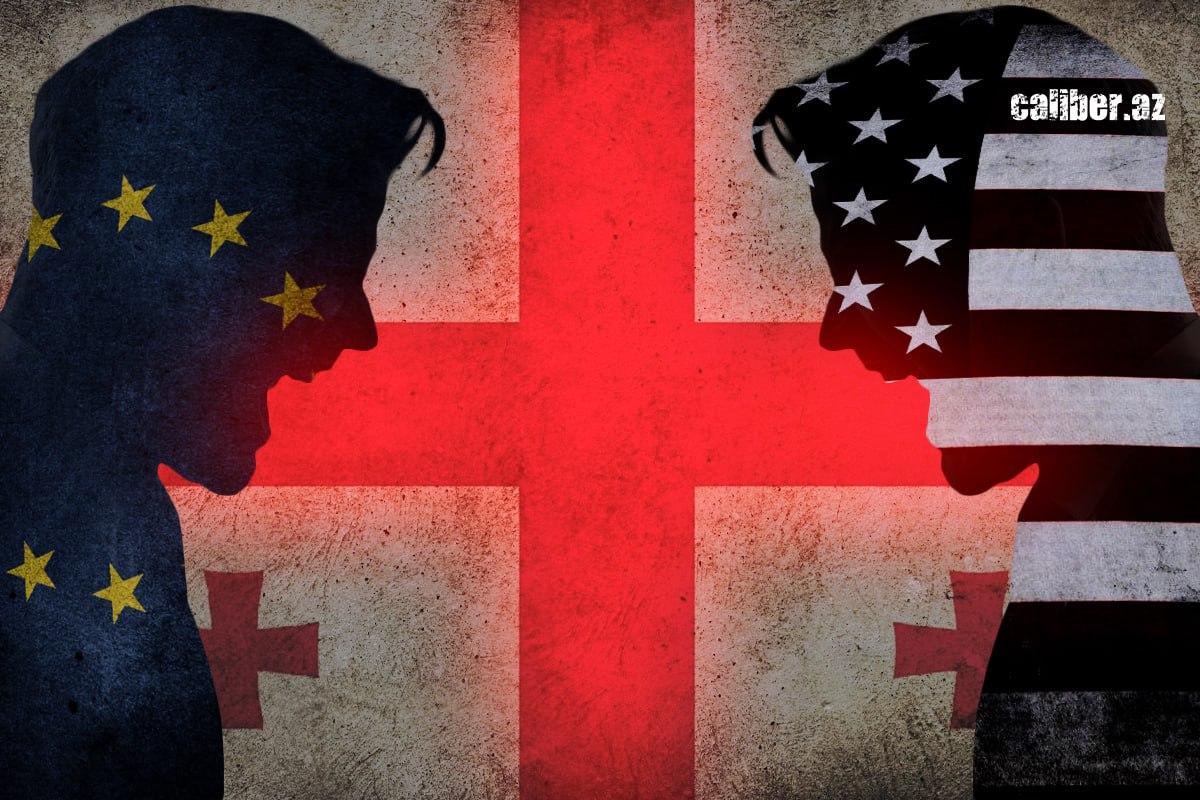

Cold War in the heart of the Caucasus EU vs. Georgia

The geopolitical pivot of Georgia away from the EU and the West reached its climax on November 28, 2024. On this day, the European Union and Georgia effectively declared a “cold war” against each other.

On one hand, the European Parliament adopted a resolution effectively rejecting the legitimacy of Georgia's parliamentary elections, consequently questioning the "legitimacy" of the current Georgian government. On the other hand, Georgia announced a freeze on its path toward EU membership—initially until 2028. However, given the uncertainty surrounding the future of both Georgia and the EU, this freeze may well become permanent.

The tension culminated overnight on November 28-29 in a “local battle” of this cold war on Rustaveli Avenue in the heart of Tbilisi. Law enforcement forces quelled another attempt by outgoing President Salome Zourabichvili, a French citizen, and the pro-European opposition to stage a "Maidan"-style uprising.

On November 28, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze and his government were confirmed by the newly elected parliament. On the same day, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for new parliamentary elections in Georgia, the imposition of sanctions on leaders of the Georgian Dream party, and the suspension of Georgia’s visa-free regime with the EU.

Although the resolution is advisory in nature and constitutes a political statement, it carries weight in shaping decisions made by EU governing bodies and European national governments.

In response, Irakli Kobakhidze announced that the Georgian government had decided to remove the issue of opening EU accession talks from its agenda until 2028 and to decline further European grants intended for the government.

Following the Prime Minister's "anti-European" statement, President Salome Zourabichvili, whose term ends on December 16 of this year, held a meeting with Western ambassadors and opposition leaders. Later in the evening of November 28, opposition leaders and Zourabichvili called on supporters of the "European choice" to take to the streets in protest.

Zourabichvili accused the Georgian authorities of a "constitutional coup" and declared herself the "only legitimate representative of power in Georgia." However, once again, the police and law enforcement acted swiftly and effectively, neutralizing provocateurs and dismantling barricades that protesters had begun to erect on Rustaveli Avenue.

The events unfolding in Georgia are undoubtedly tied to a challenging period for the European Union (evidenced by the euro’s decline against the dollar on November 28) and an extraordinarily critical moment for Russia—arguably the most severe in its modern history. Russia is in dire need of allies and friendly nations, now more than ever. However, these allies must not demand the diversion of Russia's limited military resources, unlike Syria.

It is symbolic that on the same day, November 28, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whose army is facing catastrophic losses to opposition forces near Aleppo, urgently flew to Moscow to request emergency assistance. Ironically, in return for past military aid, the Kremlin had demanded Assad recognize the so-called "independence" of separatist Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which Syria obediently did in 2018. However, since then, the geopolitical situation has shifted significantly—and not in Russia’s favour.

Moscow’s years-long attempt to construct a "new post-Soviet order," based on disregard for the territorial integrity of neighbouring states, is proving ineffective. The "imperial games" of creating supposedly "ally" separatist quasi-states on foreign territories have backfired. One of these entities, Abkhazia, has rebelled despite being entirely dependent on Russian support, overthrowing its puppet "president."

This rebellion is unfolding during Russia’s most precarious conflict: Ukrainian forces have entered Russia’s internationally recognized territory in the Kursk region, and the major Black Sea port of Novorossiysk could become a target for missile and drone strikes at any moment. In short, Russia is in a state of crisis.

If Georgia's pro-Western opposition were to come to power, it would almost certainly open a "second front" against Russia—a scenario that could spell disaster for Georgia itself.

The fact that Georgian Dream managed to win the elections and, despite unprecedented pressure, refuses to "surrender" to the West and the pro-Western opposition has effectively created the first "window of geopolitical and logistical opportunities" for Russia since the beginning of the war in Ukraine. To capitalize on this opportunity, Russia would need to genuinely establish friendly, neighbourly relations with Georgia—something that implies the beginning of a process to return the occupied territories. This, in turn, could give Georgian refugees a chance to return to their homes sooner than they had recently dared to hope.

However, in the context of Georgia’s "geopolitical pivot," the blow against Georgia and its current government from an increasingly hostile West may come from an entirely unexpected direction. The West has started to openly admire and praise the Abkhazian separatists and the so-called "Maidan" in Sukhumi, portraying their "love of freedom" as a counterpoint to the Georgian government, which they accuse of allegedly "leading the country into Russian slavery."

Pro-Western Georgian blogger Tengiz Ablotiya recently stated, "For me personally, from today onwards, Abkhazia is an independent entity." Ablotiya also argued that "Georgia doesn’t even deserve what it currently has." Such statements are surprising, especially coming from someone who is himself a refugee from Abkhazia. However, it’s essential to consider who his "employer" is: Echo of the Caucasus, a project funded by US-backed Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

The West is rapidly shifting its priorities and "favourites" in the South Caucasus. Recently, Polish President Andrzej Duda participated in an anti-Azerbaijani propaganda event organized by the EU and Yerevan near the Azerbaijani village of Karki, still occupied by Armenia. Meanwhile, Armenia is discussing visa-free travel with the EU—the very privilege the European Parliament is threatening to revoke from Georgia.

This is happening despite the fact that Armenia has not formally withdrawn from the CSTO or the Eurasian Economic Union and remains nominally a "partner" of Russia. Armenia has managed to cleverly sell its "pivot away from Russia" to the West, while simultaneously staying a full-fledged participant in Russian-led integration projects and earning significant profits from circumventing Western sanctions against Russia—particularly through the re-export of gold and diamonds. The EU, for its part, turns a blind eye to Armenia’s cooperation with another "pariah," Iran.

Given this, what would stop the West from supporting Abkhaz separatists? Especially since pro-Western NGOs, which operate freely in separatist Abkhazia, played a key role in the recent "Maidan-style" events there. Moreover, it’s not just the Abkhaz who are staunchly opposed to the return of Georgian refugees—the Armenian community in Abkhazia is even more adamant in its separatist stance.

As a result, the geopolitical situation in the South Caucasus has become an intricate "knot" that is difficult to untangle. Armenia's pivot from Russia to the West—targeted less against Russia and more against Türkiye and Azerbaijan—combined with Georgia's simultaneous "break" with the West, creates "isolated enclaves of instability."

Yerevan continues to arm itself, counting on Western support, but it can no longer realistically rely on a "corridor" through Georgia to sustain these efforts. This disconnect further complicates regional dynamics and undermines any cohesive strategy for stability in the South Caucasus.

The West, however, has no intention of "letting go" of Georgia so easily, especially given that the issue of restoring Georgia's territorial integrity—violated by Russia—remains unresolved. Western involvement in this process seems almost inevitable, as evidenced by the "Maidan-style" unrest in separatist Sukhumi.

This dynamic complicates efforts to normalize relations between Russia and Georgia, despite the objective need for the two countries to find common ground at this critical juncture. In such circumstances, strategic cooperation with Azerbaijan and Türkiye—both of which fully recognize Georgia's territorial integrity—becomes essential for the Georgian government to ensure its survival and preserve its sovereignty.

Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, for Caliber.Az