Azerbaijan-Armenia: claims and counterclaims – who is right and why? Contemplations with Orkhan Amashov/VIDEO

In his latest “Contemplation”, Orkhan Amashov expounds on why Armenia’s constitution is not merely a formal obstacle impeding the conclusion of a peace deal with Azerbaijan, but one capable of causing practical difficulties, together with other issues falling within the rubric of the claims and counterclaims swirling amidst the Baku-Yerevan diplomatic discourse.

Armenia’s constitution and wider legislation contain territorial claims against Azerbaijan. This is a well-known fact, acknowledged by everybody, including the political leadership of Armenia. In the view of Baku, the presence of such provisions constitutes an obvious obstacle impacting the conclusion of a peace deal between these two nations and the matter should be addressed expeditiously in advance.

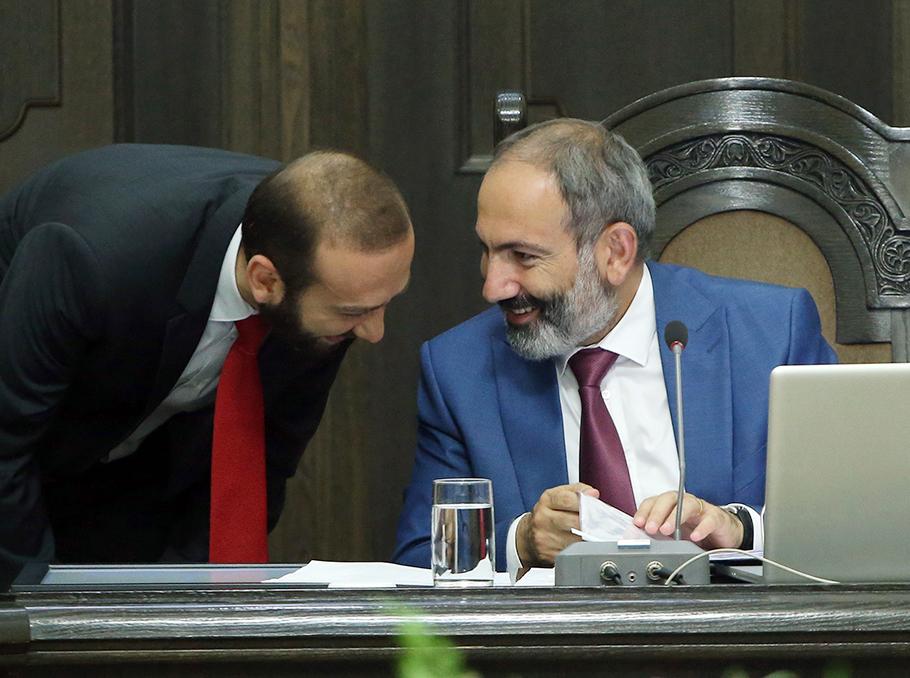

On 18 January of this year, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan acknowledged this issue, by stating that “new geopolitical and regional realities require a new constitution in order to keep Armenia viable and competitive”.

Subsequently, in an interview given to Armenian Public Radio on 31 January, he employed a metaphorical device to explain the gravitas of the situation, saying that the existing constitution was akin to wearing red clothing in order to provoke Armenia’s “hostile neighbours”, the inference being that Azerbaijan and Türkiye were bulls. It is worth remembering that the 1990 Declaration of the State Sovereignty of Armenia contains a provision also amounting to territorial pretensions against Ankara.

Nevertheless, as of June 2024, the official view maintained by Yerevan regarding this matter is not one of accelerating the process of removing the “miatsum” clause, but one of somewhat procrastinating its ditching, thereby downplaying its practical role.

In a nutshell, what Armenia says is supported on four pillars.

First of all, changes and amendments to the constitution or the adoption of a new one is within the realm of its internal affairs, the original idea having emerged in 2018 but, due to certain circumstances, no tangible implementation move has been made.

Secondly, the subject in question is not part of the Azerbaijani-Armenian peace process, with Baku’s demands to this effect being an interference in Yerevan’s internal affairs.

Thirdly, Yerevan argues that, since both sides agreed on a treaty provision, stating that no party would be able to refer to its internal legislation in order to obviate its obligations emanating from the agreement, such a demand from Baku is deemed unnecessary.

Fourthly, the Armenian leadership has recently developed a novel argument stating that, according to Yerevan, the Azerbaijani Constitution also contains territorial pretensions against its neighbour.

Naturally, Azerbaijan has reposts to all of these points. Let us deal with them separately.

Firstly, Armenia’s constitution is, in principle, its internal matter, but when one nation’s legislation contains territorial claims on another, the latter is entitled to demand that this be remedied, particularly when these two countries aim to sign a deal on the basis of, inter alia, the mutual recognition of territorial integrity and sovereignty.

Secondly, it is not a matter of concern to Baku as to how the constitutional referendum will be framed inside Armenia, but what matters is that there should be nothing left in its legislation casting aspersions on Azerbaijani sovereignty.

Thirdly, the inclusion of a provision on non-reference to domestic legislation is important, but insufficient.

It is true that Article 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states that “a party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty”. On this basis, one may tentatively and somewhat prematurely conclude that, once the treaty is ratified, the whole subject should be done and dusted. However, it is not as simple as that. Let us consider potential snags.

In the first instance, the ratification process in Armenia may prove problematic. Article 116 of this nation’s constitution states that: “international treaties contradicting the Constitution may not be ratified”. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Yerevan will overcome this hurdle, with the judges of the Constitutional Court issuing their approbation despite the 1990 Declaration, and the parliament completing ratification.

Could those replacing Pashinyan and Co question the validity of such a treaty as contradictory to Armenia’s constitution? The answer is that they could, and given Armenia’s three-decades-long mental

gymnastics over the Karabakh issue and the skulduggery involving the Alma-Aty declaration, nothing should be deemed unthinkable.

Article 46.1 of the self-same Vienna Convention says that: “a state may not invoke the fact that its consent to be bound by a treaty has been expressed in violation of a provision of its internal law regarding competence to conclude treaties as invalidating its consent unless that violation was manifest and concerned a rule of its internal law of fundamental importance.”

Is it utterly beyond the realm of probability that those succeeding Pashinyan may argue that, whilst expressing its consent to be bound by the treaty, the Armenian government manifestly violated some internal rules? This is more than possible, in particular, bearing in mind that many of those currently in the opposition claim Pashinyan has no right to sign a surrender act.

In fact, there are some other articles enshrined in the Vienna Convention that could be referred to by the revanchists to cast aspersions on the validity of the treaty. For instance, Article 50 says that: “if the expression of a State’s consent to be bound by a treaty has been procured through the corruption of its representative directly and indirectly by another negotiating State, the State may invoke such corruption as invalidating its consent to be bound by the treaty.”

What I am effectively trying to say here is that, given that the internal detractors of Pashinyan, as of today, are pejoratively calling him a Turk and questioning his legitimacy, and describing him a traitor intent on unlawfully selling Armenia, is it impossible that, if the opposition manages to somehow overthrow the current government or replace it in elections, they will also question the validity of the treaty with Azerbaijan on some fabricated and imaginary pretexts?

The answer is we cannot exclude anything. Indeed, it is true that if Armenia decides to act in this fashion, it will look foolish and grossly unreasonable in the eyes of the international community, but such a mode of action has not been anathema to this nation’s foreign policy agenda over the past 30 years, including the period under Pashinyan too.

The fourth element in Yerevan’s present recalcitrance regarding the speedy resolution of the problems emanating from its legislation is that Armenian Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan has recently reiterated the view, stated in January, that the Azerbaijani Constitution also contains provisions that may amount to territorial pretensions against Armenia.

Since I have already spoken rather extensively today, allow me to be succinct, and merely say that Armenia is trying to create a false equivalence between its own constitution and that of Azerbaijan for a number of reasons, including that related to making itself look plausible. It is not just that there is no equivalence of “miatsum” in the Azerbaijani constitution, but that the latter’s entire legislation is without any provisions remotely amounting to territorial pretensions on any other nation.

Since I intend to dedicate a separate Contemplation to this claim, I will adhere to brevity here, confining myself to saying that Armenia argues that, since Article 2 of the Constitutional Act on the State Independence of Azerbaijan acknowledges that modern Azerbaijan is the successor to the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic (ADR) which existed between 1918-20, as of today Baku may have a claim over the entire territory of the former ADR, comprising 114,000 square kilometres.

As far as the legal argument and the question as to whether there is anything in the Azerbaijani constitution amounting to an obstacle impeding the peace treaty, the claim is unfounded. Baku has never adopted any legislative act giving rise to such an interpretation of the aforementioned provision of the Constitutional Act and, in the context of the transmission of the legal personality in international law, when Azerbaijan regained its independence in 1991, it re-emerged on the international scene with the rights and obligations of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan. The subject has its own inherent intricacies and there are nuances worthy of exploration, and I will get back to this later this week. However, for today’s discussion it would suffice to say that Azerbaijan has made no territorial claim towards Armenia.

So, over the past three decades, Armenia adopted specific legislative acts on the basis of its Constitution, with the most notable being the 1992 decision of its parliament, all of which were later referred to by its national courts and official correspondence, cumulatively revealing, in the clearest possible way, that so far as its legislation is concerned, Armenia does not recognise Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan. This is obvious.

What Azerbaijan demands is clarity and the removal of ambiguity, which Armenia is not capable or willing to provide Yerevan argues that all of these amendments would require a constitutional referendum, which will take some time. We also understand that there is no guarantee that Pashinyan will win the vote, and therefore he is presently vacillating, showing his willingness to sign some sort of deal without initially sorting the constitutional obstacles.

Furthermore, if the Armenian electorate is not yet ready to say a firm farewell to “miatsuim”, perhaps we should wait and allow Pashinyan to go through all the procedural nitty-gritty necessities, preparing the nation for a durable and long-term peace. What underpins this bizarre urgency?

The Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry has recently claimed Armenia has a secret agenda. On the basis of the possibilities outlined above, this indeed may be the case. Prevarication reigns supreme.