Red Cross — grey schemes: Three decades of anti-Azerbaijan policy From espionage to smuggling

It all begins with trust, especially in moments when the world is falling apart. When your home lies in ruins and your loved ones are being searched for under the rubble, any word about humanitarianism sounds like salvation. It is in such moments that the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) appears on the doorstep — an organisation with a century-and-a-half-long history and a name that evokes associations with nobility. But in the case of Azerbaijan, as the past three decades have shown, the Red Cross has come to symbolise not compassion, but political calculation, covert pressure, and double standards.

But let’s start from the beginning.

The ICRC began operating in Azerbaijan in the early 1990s — during one of the country's most profound national tragedies. Following the collapse of the USSR, the country descended into chaos: Armenian occupation, over a million refugees and internally displaced persons, thousands of hostages and missing people. Under such conditions, no one read the charters or memoranda. Humanitarian aid was desperately needed — at any cost. The Red Cross took advantage of this — as it turned out, not only for the sake of humanity.

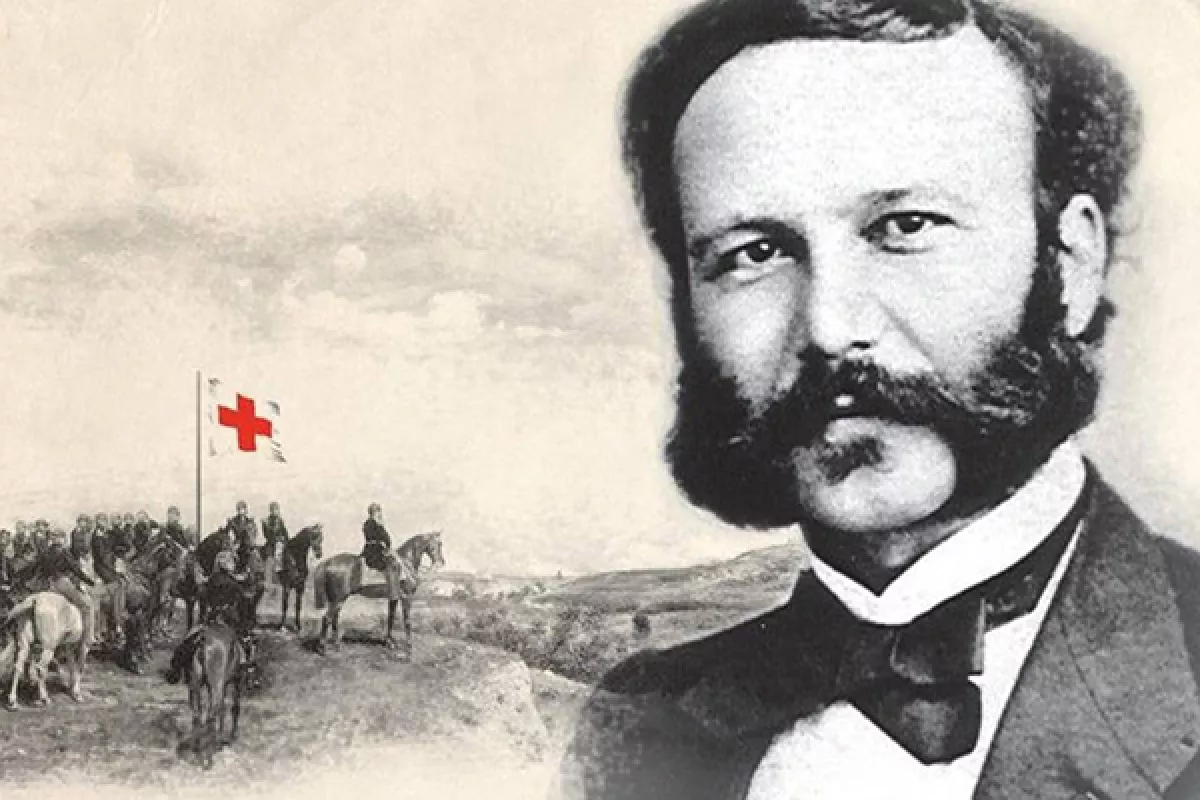

The organisation that officially calls itself “international” is, in reality, a Swiss NGO. All key positions are held by Swiss nationals. The fact remains: throughout the Committee’s entire history, dating back to the 19th century, all 16 of its presidents have been exclusively Swiss citizens. This mono-national leadership at the helm of a supposedly global “international” organisation raises serious questions about discrimination and the true nature of its operations. It promotes its “neutrality” as a virtue, but this is more of a smokescreen. The Red Cross’s actual agenda has always been shaped by the interests of Switzerland and its Western partners. While in the days of ICRC founder Henry Dunant the cause was genuinely about compassion, in today’s world the Red Cross has largely lost its humanitarian essence, transforming into a tool of foreign policy influence.

History contains moments that expose the truth more powerfully than any words. During World War II, for instance, the ICRC effectively helped the Nazis conceal the Holocaust by taking part in a charade at the so-called “model” concentration camp of Theresienstadt. Decades later, a similar performance unfolded in Karabakh — once again with the Red Cross involved, albeit in a different historical context.

The Karabakh theatre under the guise of humanitarianism

Azerbaijan did not choose the Red Cross — it had no choice. As mentioned earlier, in a country devastated by war and suffering from an acute shortage of resources, the organisation quickly established its presence. But it soon became clear that this was not a neutral humanitarian mission, but rather a structure that consistently ignored Azerbaijan’s sovereignty. And this is not a matter of opinion — below, we present concrete facts that demonstrate this pattern of behaviour.

Nearly 4,000 Azerbaijani citizens were taken prisoner during the First Karabakh War. Despite officially documented evidence and its own internal correspondence — including letters from 1998 and 2001 in which the ICRC confirmed that 54 Azerbaijanis were held in captivity — the organisation failed to ensure the return of the majority of them. Armenia returned only 17 bodies. The fate of the remaining 37 individuals remains unknown. The ICRC, despite repeated appeals from Baku, remained silent.

In 2005, when Armenia began illegal archaeological excavations in the Aghdam district and attempted to present the Shahbulag Fortress as the so-called "Tigranakert," the ICRC found neither the words nor the will to condemn this blatant distortion of historical truth. On the contrary, through its silence, it effectively facilitated the erasure of Azerbaijan’s cultural heritage.

In 2020, during the 44-day Patriotic War, the organisation not only failed to assist Azerbaijan in restoring international law — it actively interfered. ICRC representatives made attempts to slow down the advance of Azerbaijani Armed Forces in the Fuzuli region, held meetings with military officials under the pretext of humanitarian negotiations, and, near Lachin from the Gubadli side, insisted on meeting Azerbaijani forces. The goal was to determine whether Azerbaijan planned to take control of the Lachin corridor. These actions were widely interpreted as an attempt to gather intelligence under the guise of humanitarian engagement.

Humanitarian facade, political motives: The year 2023

The year 2023 marked a turning point — and an exposure. Under the pretext of a "humanitarian crisis" in Karabakh, a large-scale propaganda campaign was launched. At its core was the narrative of "starving Armenians" in the region. Despite Azerbaijan’s open and official proposal to deliver aid via Aghdam — with humanitarian cargo from the Azerbaijan Red Crescent Society waiting on standby — the ICRC not only refused to support this initiative, but also pressured the Red Crescent to abandon these genuinely humanitarian actions.

At the same time, Western and Armenian media — with the ICRC’s tacit cooperation — were spreading myths of a “genocide” in Karabakh. The culmination of this campaign was a report by the notoriously controversial Luis Moreno Ocampo, former prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. His accusations, unsupported by any factual basis, were bolstered solely by the fact that Red Cross staff continued meeting with armed militants in Khankendi. There was nothing “neutral” about this behaviour.

Notably, the ICRC office in Yerevan, despite lacking any mandate to operate in Azerbaijan’s Karabakh region, regularly commented on the situation, while the organisation’s Baku office remained silent. But silence is not always considered as neutrality. Sometimes, it is a form of complicity with falsehood.

By July 2023, attempts at smuggling were documented. ICRC vehicles passing through the Lachin checkpoint were stopped carrying large quantities of mobile phones, cigarettes, accessories, and fuel. Rather than taking steps to address or stop these violations, the organisation outright denied they had occurred. As a result, Azerbaijan temporarily restricted the Red Cross’s access through the checkpoint. According to some reports, the organisation had also been transporting Armenian residents of Karabakh to Armenia for a fee — mixing humanitarian work with profit-driven activity.

Against this backdrop, Swedish journalist Rasmus Canbäck — a long-time purveyor of propaganda for the Armenian diaspora — published an article on the OCCRP platform containing a series of fabrications against Azerbaijan. As it turned out, the source of the information was the ICRC. Or more precisely, a story about the ICRC’s “difficult work,” as told by unnamed insiders from within the organisation. According to their account, and as concluded by the article’s authors, Azerbaijan allegedly obstructed the movement of humanitarian convoys from Armenia along the Lachin road to Armenian-populated areas in Karabakh.

In an editorial on our website, we demonstrated that OCCRP’s report — among other things, albeit perhaps unintentionally — exposed the ICRC itself. Rather than pursuing legal and ethically sound channels to address its concerns, the ICRC resorted to questionable insider leaks. If Azerbaijan had truly violated its obligations under the Geneva Conventions, the ICRC would have had numerous legitimate avenues to respond. The fact that it chose backdoor leaks instead only underscores its lack of confidence in defending its position through proper legal means. Azerbaijan, after all, possesses not only capable commanders and soldiers, but also highly qualified legal experts.

An illegal office, secret agreements, and a network of intelligence

But let’s rewind the clock. In 1994, without notifying Azerbaijan, the ICRC signed a “memorandum of understanding” with the occupying regime in Karabakh. By the early 2000s, the organisation had opened an office in Khankendi — again, without informing Baku. Azerbaijan’s demand to see the text of the agreement was ignored under the pretext of “confidentiality.”

The Armenian side openly cited this “memorandum” as alleged evidence legitimising the separatist regime. In 2023, Armenia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs bluntly declared that the ICRC’s activities in Karabakh are conducted on a legal basis and cannot be restricted by Azerbaijan.

The Khankendi office did not report to Baku — but to Geneva and Yerevan. Until 2005, operations in Karabakh were listed in ICRC reports as being conducted “outside of Azerbaijan,” and publicly released maps showed the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast as directly connected to Armenia. From 2020 until the 2023 anti-terror operation, this office effectively served as an intelligence outpost advancing Western interests. According to our information, Baku possesses specific data identifying ICRC personnel involved in espionage activities.

In 2023, Azerbaijan officially demanded the closure of the office. The ICRC’s response was defiant: “We believe that the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia is not over. There are ‘de facto controlling structures’ in Karabakh. We will reconsider our position after 2025.” This was the final straw. The office was shut down.

Espionage, provocations, and information subversion

Under the guise of humanitarian work, ICRC personnel in Azerbaijan frequently engaged in information gathering. Some individuals were expelled — including one staff member from Lebanon, caught conducting espionage. In 2018, following unrest in Ganja, ICRC representatives visited detainees and allegedly encouraged them to go on hunger strikes and seek asylum at the French and German embassies.

Former Committee staff members later made partisan statements at international forums. Since Azerbaijan restored its territorial integrity, such statements have become more frequent.

At one closed meeting, the ICRC’s Regional Director for Europe and Central Asia, Ariane Bauer, claimed that Azerbaijan allegedly planned an offensive against southern Armenia and expressed concern about the ICRC’s diminishing influence in the region amid the war in Ukraine.

Mission subverted: How the humanitarian emblem became part of a geopolitical game

Azerbaijan’s case is not unique. The same pattern of behaviour by the ICRC has appeared in other conflict zones. Ukraine, facing full-scale aggression from Russia, has also accused the Red Cross of sabotaging humanitarian missions. Kyiv officially stated that the ICRC refused to participate in evacuating civilians, failed to document crimes against prisoners, and effectively shirked its mandate.

All of this confirms one clear truth: this is a systemic devaluation of the humanitarian mandate. In other words, the ICRC has lost its universal character and increasingly acts selectively — dictated by political circumstances.

The story of the ICRC is not an isolated episode. It is a pattern. Over thirty years, the Red Cross in Azerbaijan systematically replaced humanitarianism with politics. Opening an office in Khankendi, sabotaging prisoner issues, participating in biased campaigns, smuggling, espionage — all these became parts of a single logic: exerting pressure under the banner of humanity.

Azerbaijan has broken free from this trap. Expelling the Red Cross was an act of sovereign restoration of justice. This is a lesson for all: even those who hide behind noble symbols must abide by the rules. Sovereignty is not a gesture — it is a boundary of dignity. It is neither negotiable nor bypassable. It must be defended. And that is exactly what Azerbaijan did.