Türkiye and Syria share the sea A new game in the Eastern Mediterranean

A letter signed by Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has become the first clear confirmation that, following the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Ankara is conducting secret negotiations with the new government in Damascus. Their goal is to define maritime boundaries between Türkiye and Syria.

According to the letter, several Turkish government agencies have been tasked with developing an agreement on an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) with Syria.

“With the overthrow of the Baath regime and the transfer of power to a transitional government, efforts are being carried out in coordination with our relevant institutions to determine the maritime boundary with Syria and to delimit maritime jurisdiction areas beyond territorial waters, in a way that protects our country’s rights and interests,” Fidan wrote in the letter dated June 16, addressed to the office of the Speaker of the Turkish Parliament.

Fidan also rejected claims that Türkiye had allegedly promised not to conclude a maritime agreement with Syria.

“It would be beneficial to take into account the official statements and declarations made by our ministry on this matter,” he noted, adding: “The EU has no right to comment on a potential agreement between two sovereign states regarding their maritime jurisdiction areas.”

Such a deal could pave the way for joint exploration and development of transboundary hydrocarbon resources by Türkiye and Syria. Given that Damascus currently lacks offshore drilling capabilities, Ankara would likely lead the technical efforts under such an agreement. It is also noteworthy that Türkiye has long been a partner of the ruling Syrian organisation HTS (Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham), led by Ahmed al-Sharaa, which overthrew the Assad regime in December 2024.

In 2019, Ankara signed a maritime border agreement with Libya’s internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA). As a result of this deal, Türkiye extended its influence over significant offshore gas fields and potential pipeline routes that could have been used to export fuel to Europe by Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel. Unsurprisingly, these four countries strongly opposed the Turkish-Libyan agreement, and were soon joined by other discontented parties.

In response to the Türkiye-Libya maritime memorandum, the European Council stated on December 12, 2019, that the agreement violated the sovereign rights of third countries, did not comply with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and could not produce any legal consequences for uninvolved parties.

Above all, the deal sharply escalated tensions between Türkiye and the Libyan GNA on one side, and Greece and Egypt on the other. Athens and Cairo had long cooperated on the development and exploitation of gas fields. Both countries are members of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), established in 2018 to promote a regional energy market and ensure the export of natural gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe.

In addition to Greece and Egypt, the forum includes Cyprus, France, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestine as full members, while the European Union, the World Bank Group, and the United States participate as observers.

The EU, keen on diversifying its gas sources, had set its sights on Eastern Mediterranean energy resources, planning to finance the construction of the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline (EastMed).

By the early 2020s, a so-called "energy triangle" had emerged—an alliance of Greece, Israel, and Cyprus focused on offshore gas extraction in the Mediterranean.

In January 2020, Greece, Cyprus, and Israel signed an agreement to build the EastMed pipeline, intended to transport gas from Israel’s Leviathan field and Cyprus’s Aphrodite field to mainland Europe. As a result, Israel sided with Greece in the growing regional conflict.

Furthermore, Egypt’s allies—the UAE and Saudi Arabia, two of the wealthiest and most militarily advanced countries in the Gulf—also joined the opposition to Türkiye and Libya’s GNA.

Thus, by signing the maritime demarcation agreement with Libya, Türkiye found itself facing a broad coalition of opponents.

In response, Greece and Egypt signed a similar agreement delimiting their maritime boundaries, asserting that certain areas of the Eastern Mediterranean belong to them—not Türkiye. This escalated the risk of sanctions and military confrontation over these disputed but resource-rich maritime zones.

France, backing Greece and Egypt, drew “red lines” and pledged military intervention on Athens’ side in the event of armed conflict. There were also several incidents involving Greek and Turkish naval vessels.

While Israel did not seek an open conflict with Türkiye, it actively cooperated with Ankara’s opponents by conducting joint special forces exercises with the Greeks and Cypriots, as well as naval manoeuvres involving the Greek Navy.

This situation proved unfavourable for Türkiye, which faced a powerful coalition. Additionally, the United States also sided with the critics of Ankara.

However, starting around 2022, Türkiye began pursuing a more flexible foreign policy aimed at reducing regional tensions. A process of normalising relations with Egypt, Greece, Saudi Arabia, and the Emirates was launched. This rapprochement was rapid: Türkiye restored ties with many countries and began receiving multibillion-dollar investments from Gulf states. This shift was driven by two key factors—geopolitics and economics.

Firstly, the emerging configuration of military-political blocs threatened Ankara with an expensive confrontation that could have cost far more than the potential benefits from exploiting gas fields. Moreover, in a climate of confrontation with Europe, exporting gas in that direction would become impossible.

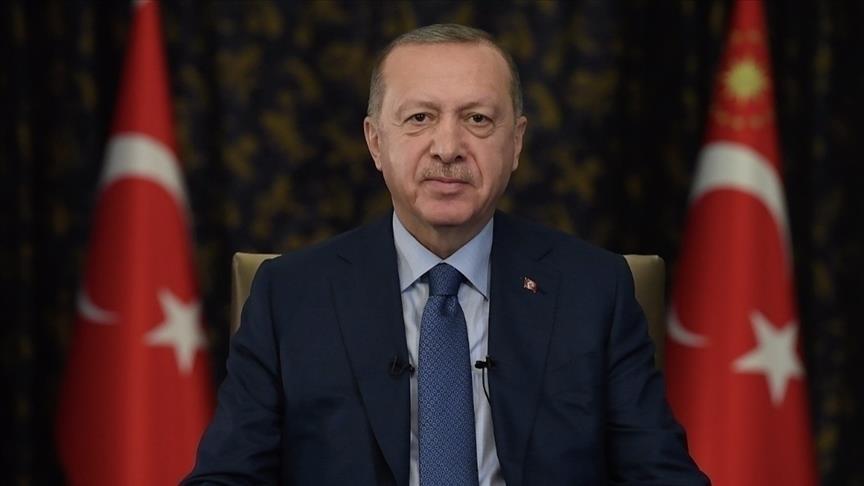

Secondly, economic difficulties—rising inflation and investor outflows—pushed President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to abandon confrontation. Especially given Türkiye’s need for investments from Europe and the United States, with the European market remaining crucial for its export-oriented economy. The rapprochement with recent rivals has brought benefits to Ankara—investors, including energy powers from the Gulf, have begun returning to the country.

The question arises: could a potential Turkish-Syrian maritime boundary agreement significantly alter the geopolitical dynamics in the Eastern Mediterranean and lead to a new international escalation? In recent years, this region has become a hotspot of conflicts. The discovery of large hydrocarbon reserves beneath the seabed has triggered numerous overlapping claims among coastal states. Could this situation repeat itself?

Theoretically, problems are possible, but in practice they are likely to be avoided. Modern Türkiye needs Western investments and market access, and apparently has no desire to get drawn into a new conflict with European and Middle Eastern countries. Its opponents, preoccupied with the European crisis and worried about waning U.S. support, are also not interested in escalating the gas dispute in the Mediterranean.

Therefore, an agreement between Türkiye and Syria is unlikely to lead to a sharp escalation. However, it will undoubtedly cause concern among Ankara’s critics, who are wary of its growing influence on the international stage.