Rare Mayan blue pigment that is cherished by art historians

In 17th-century Europe, ultramarine blue pigment was obtained from the treasured lapis lazuli gemstone mined in Afghanistan. Painting with the tint was a luxury reserved for only the most prominent artists like Michelangelo Caravaggio and Paul Rubens. This pigment, more valuable than gold, was used sparingly in paintings, often symbolizing divinity and royalty. However, across the Atlantic in colonial Mexico—then known as New Spain—vibrant blue tones appeared widely in Baroque works. This raises a question: how could a pigment so rare in Europe be prevalent in the Americas?

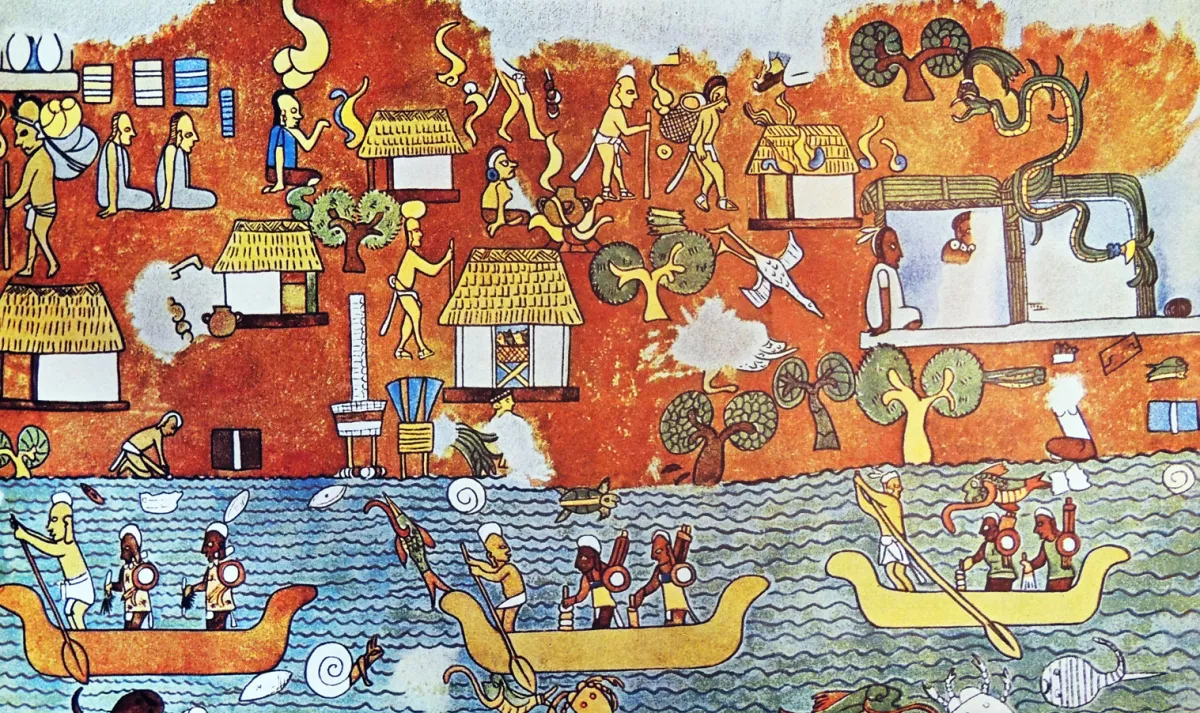

The answer lies in the innovative use of 'Maya blue', a pigment developed centuries earlier by the ancient Maya civilization. Archaeological discoveries in Mesoamerica, particularly the vivid murals at sites like the prominent temple of Chichén Itzá, shaped like a pyramid, reveal that the Maya had perfected a unique, resilient blue pigment as early as 300 AD. According to an article published on the Art trading platform ArtNet, this pigment held ceremonial importance, used to paint sacrificial altars and victims.

The durability of Maya blue, surviving centuries of natural wear, puzzled archaeologists until the 1960s when it was discovered that the pigment combined indigo dye from the añil plant with attapulgite, a rare clay. This unique formula ensured the brilliance and longevity of the color, setting it apart from the easily faded indigo used for dyes.

In colonial Mexico, local artists like José Juárez, Baltasar de Echave Ibia, and Cristóbal de Villalpando incorporated Maya blue into their Baroque works, creating vibrant compositions distinct from their European counterparts. These New Spanish Baroque artists started by imitating European aesthetics but gradually developed a unique style, marked by saturated colors, multiple light sources, and complex, layered compositions. Their use of indigenous materials like Maya blue not only expanded their palettes but also symbolized the cultural fusion of the Old and New Worlds.

Juárez’s evolution as an artist illustrates this blend of influences. Early in his career, his works reflected the dramatic lighting and warm tones of European Baroque masters like Caravaggio and Rubens. Over time, he moved toward a colder, more saturated palette with vibrant blues, yellows, and greens. These colors, made possible by local pigments as the article recalls, set his work apart from European contemporaries. Despite his innovative artistry, Juárez died in poverty, lacking the resources to afford the costly lapis lazuli imported from Europe. Instead, he relied on Maya blue, a more accessible and vibrant alternative.

The composition of Maya Blue used to be a mystery to scientists as only its two primary components were known. Recent research by Spanish scientists uncovered a third component, dehydroindigo, formed when indigo oxidizes during heating. The Live Science publication reported on this discovery, which sheds light on how the Maya may have controlled the pigment's hue.

"Indigo is blue, and dehydroindigo is yellow," explained Antonio Doménech from the University of Valencia. "The variable proportions of these pigments could explain Maya Blue’s greenish tones. The Maya might have adjusted the preparation temperature or heating time to achieve specific hues." Although a 2008 American research suggested that copal resin, used for incense, was the secret third ingredient, based on traces of Maya Blue found in a bowl used for burning incense, the Spanish team disputed this claim. Currently, the Spanish researchers are exploring the chemical bonds that link Maya Blue's organic (indigo) and inorganic (clay) components. Understanding these bonds is essential to explaining the pigment’s remarkable durability, which has preserved Maya art for centuries.

The significance of Maya blue extends beyond its artistic applications. During colonization, indigenous materials like this pigment were exploited alongside other natural resources from the new continent. The blue, once a symbol of Maya wealth and ritual, came to represent the cultural and material plunder of the New World. Nonetheless, its resilience allowed it to preserve the vibrancy of colonial Baroque art in the Americas, which remains striking to this day.

Comparing New Spanish Baroque art with its European counterpart highlights both shared influences and unique innovations. While Rubens’ works are known for their dynamic compositions and warm tones, Juárez’s paintings exhibit a cooler, more structured aesthetic. Caravaggio, whose canvases rarely featured blue, contrasts sharply with the blue-rich works of Juárez and his peers.

The legacy of these New Spanish artists challenges the notion that their work was merely derivative of European styles. Instead, their art reflects a sophisticated synthesis of indigenous and European elements, illustrating the early beginnings of cultural globalism. The vivid use of Maya blue, rooted in pre-Columbian innovation, serves as a testament to the enduring influence of the Americas’ indigenous civilizations on colonial and global art.

By Nazrin Sadigova