Saudi Aramco doesn’t believe its own rhetoric on oil demand

Bloomberg has published an article claiming that if the future is really so bright, Saudi Aramco should open its wallet and increase output rather than blaming environmentalists and ESG rules. Caliber.Az reprints the article.

Imagine if Sundar Pichai, Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg was to stand on a stage and lament that the world wasn’t building enough data centers.

Meeting our ever-growing demand for cloud storage (they might say) will require more and more racks of web servers; if we fail to produce them, the electronic systems on which modern society depends might break down. It’s hard to believe such a warning would be taken seriously if Alphabet Inc., Amazon.com Inc and Meta Platforms Inc weren’t spending the money to avert such a catastrophe. As some of the biggest players in the cloud, with the balance sheets to match, they should be treating the coming crisis as an opportunity.

That makes recent complaints from the Chief Executive Officer of Saudi Arabian Oil Co a little baffling. “ESG-driven policies” and proponents of an energy transition away from fossil fuels are contributing to underinvestment in oil and gas, Amin Nasser told a forum in Riyadh on Feb 12. That “will have serious implications. For the global economy. For energy affordability. And for energy security,” he added.

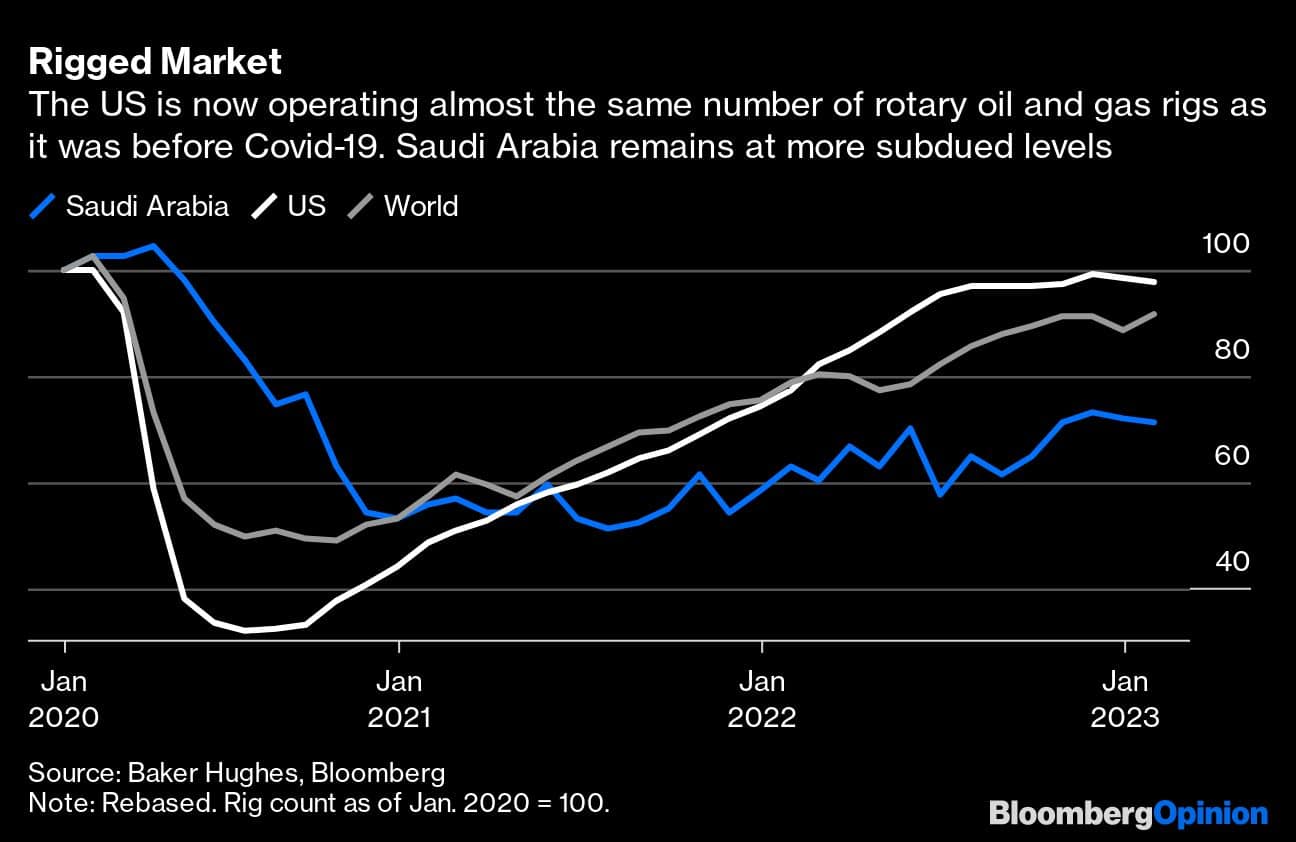

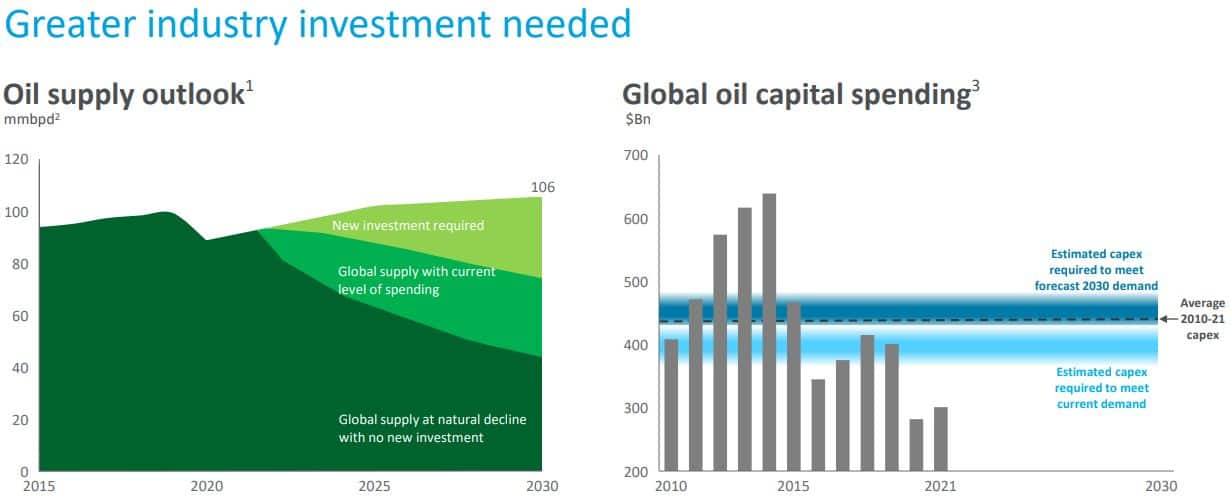

It’s a complaint Saudi Aramco has made before. Annual spending on oil and gas production is falling roughly $150 billion or so short of where it would need to be to meet levels of current and future demand, according to charts presented at half-year results last August:

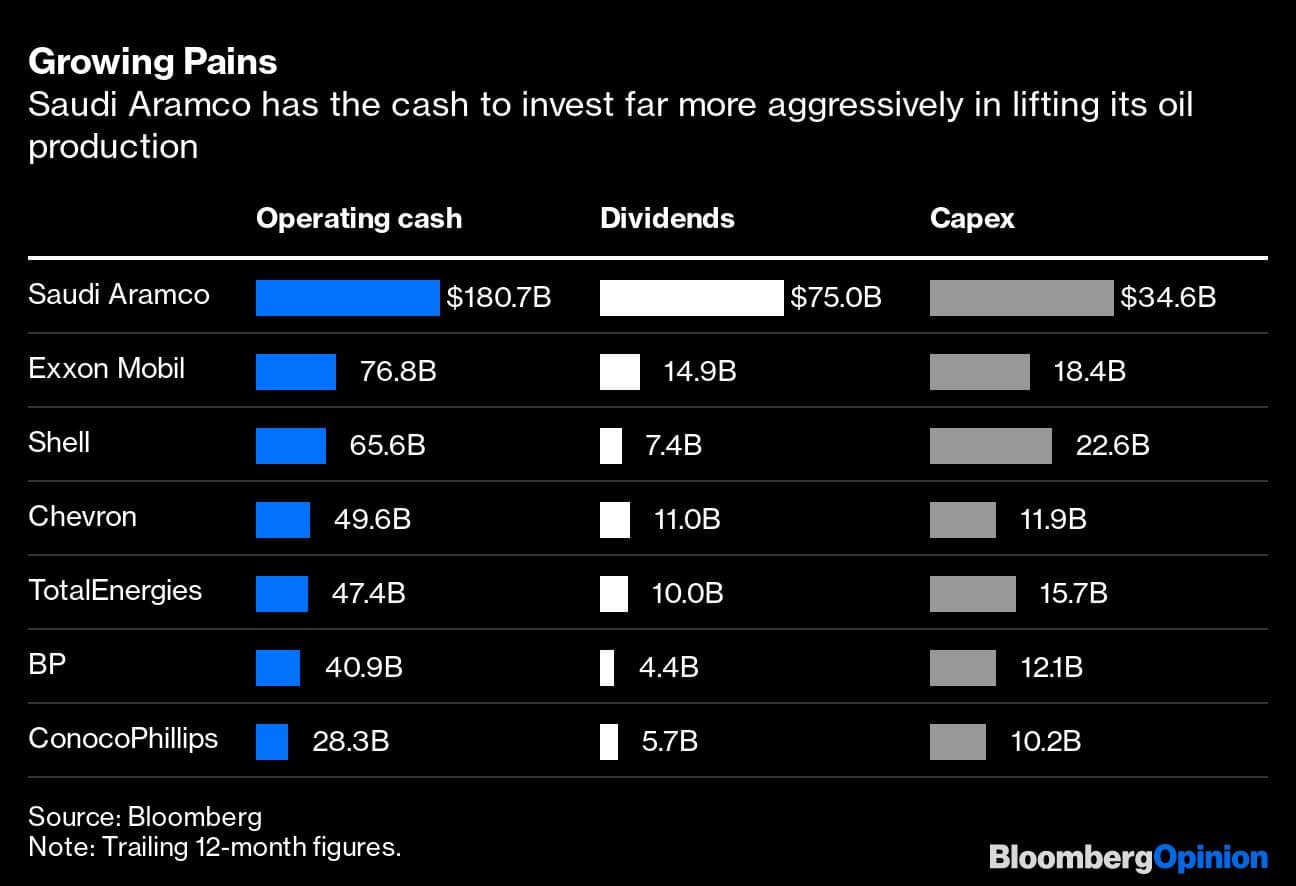

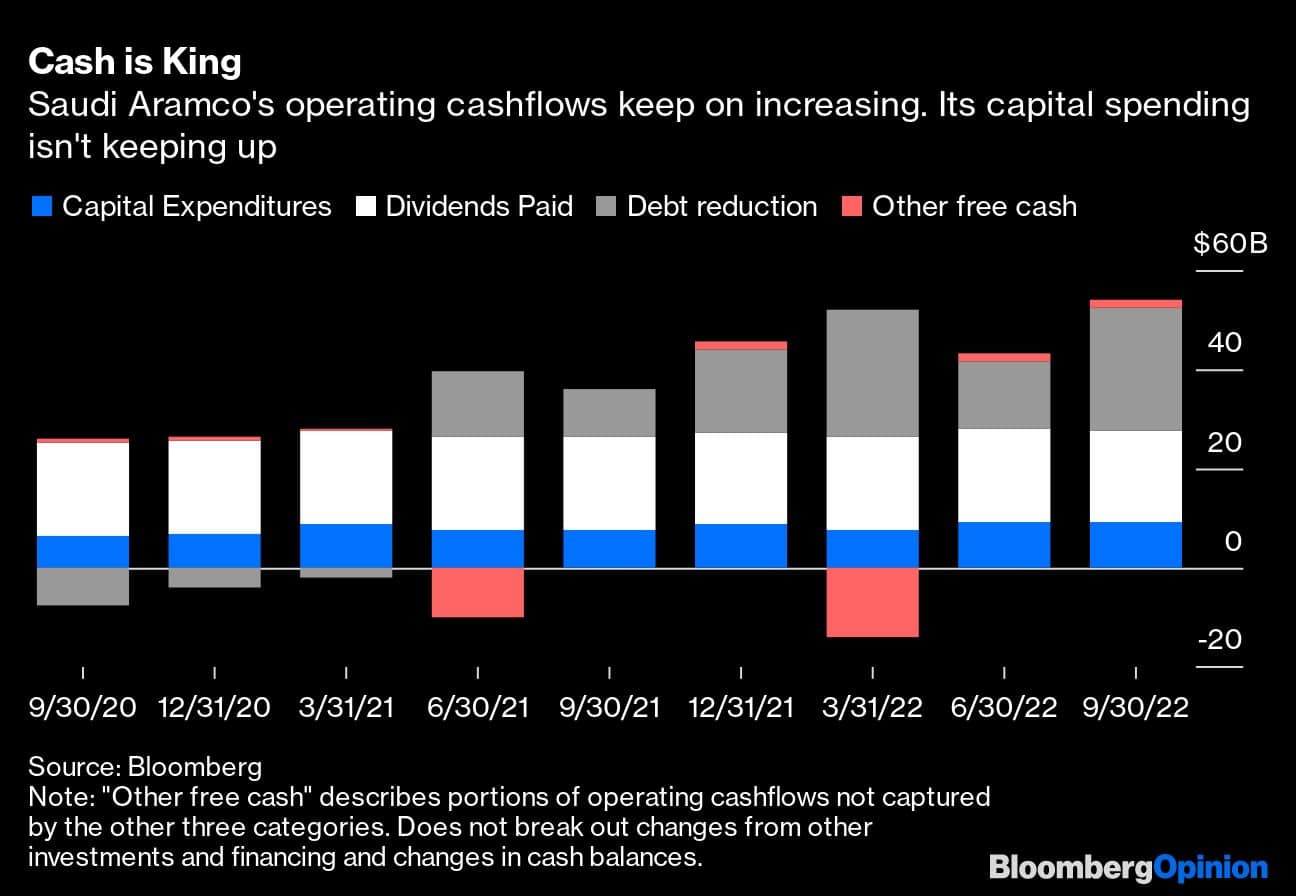

Here’s a thing, though. The company best-placed to address this looming shortfall is ... Saudi Aramco. Operating cashflows in the 12 months through September came to $181 billion — more than was posted in the same period by Exxon Mobil Corp., Shell Plc and Chevron Corp. put together.

Western rivals can point to calls for cash from demanding shareholders to explain their failure to invest as aggressively as they did in the past, as Bloomberg Opinion wrote last week. That explanation doesn’t wash with Aramco, however. All but a 1.7 percent sliver of the stock is owned by the Saudi government and its sovereign wealth fund. Moreover, the $75 billion Aramco paid out in dividends over the same period is about 50 percent more than the combined sum spent by all seven western oil majors.

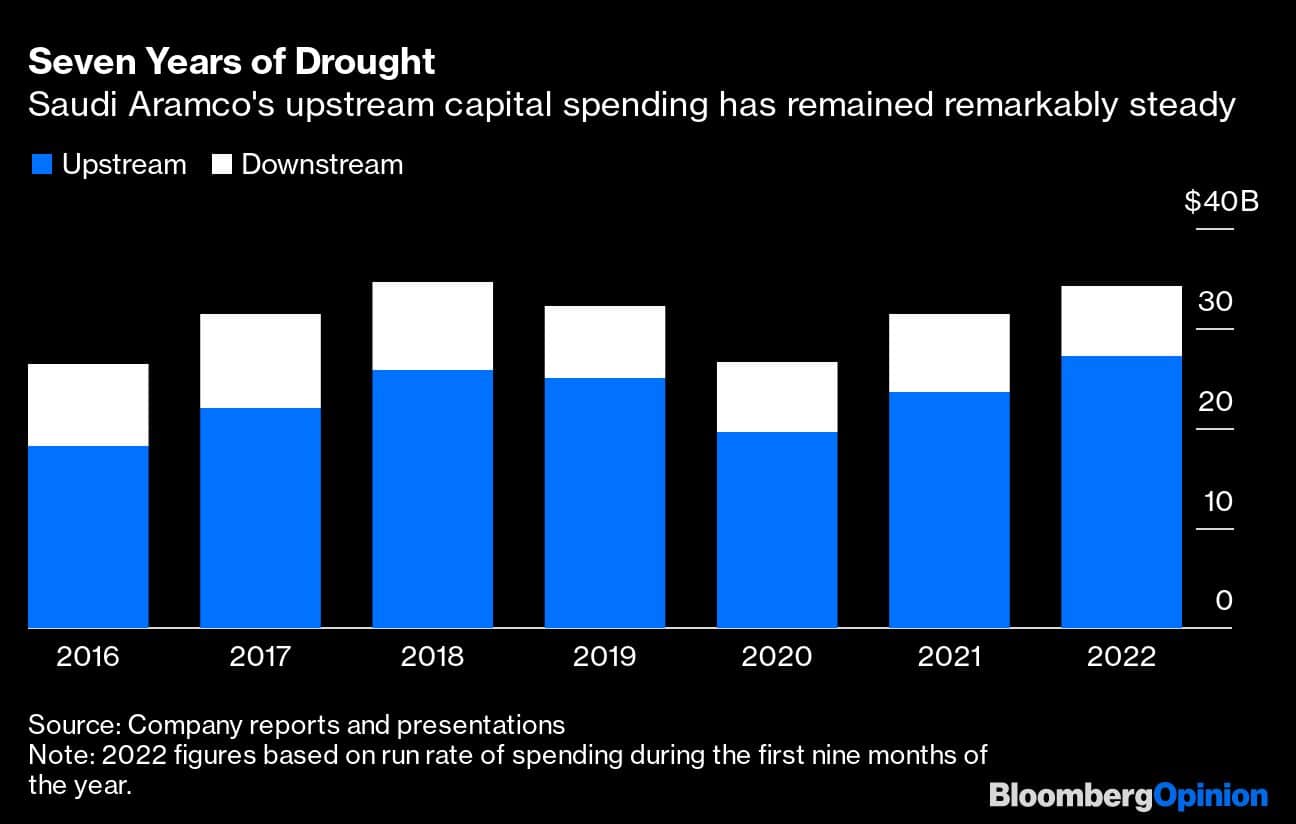

Despite this, upstream capital spending on petroleum production has failed to keep pace with profits. While total capex guidance has been boosted to a range of $40 billion to $50 billion in 2022 and more through to 2025, downstream spending on refineries and chemical plants will take up a growing share in the future. Once you include all the cash Aramco plans to dedicate to (horrors!) energy transition projects such as renewables, hydrogen, and carbon capture, upstream will only get about 50 percent of the total, Nasser told investors in August. That implies that the funds dedicated to new oil production may not head much above long-term levels around $25 billion — or even decline modestly, when you consider the effects of inflation and the vast sums Aramco is promising to spend on gas.

With shareholders already amply rewarded and capex stalling, analysts expect Aramco will have no choice but to stick its spare profits in the bank. Net debt, which totaled $80 billion in 2020, switched to net cash last year and will rise to as much as $93 billion in cash by 2025, according to median expectations surveyed by Bloomberg. Rather than spend that money to capture market share in the commodity on which its country’s wealth was built, Saudi Aramco will be left clocking up 4.5 percent or so on government bonds.

This seems like an extraordinary failure of animal spirits. If you believe Aramco, oil demand is still increasing, albeit modestly. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries will see its share of production rise to about half of the global total by mid-century, from roughly a third at present, according to BP Plc — a jump of something like 20 million daily barrels, if you assume demand holds roughly steady. And yet Saudi Aramco’s most ambitious plan is to raise its peak production capacity by just one million daily barrels, to 13 million barrels a day in 2027. Even if it thinks its domestic fields are close to maximum output levels, such rivers of cash should give Aramco a magnificent opportunity to invest overseas and buy some diplomatic goodwill for the kingdom, if it thought the opportunity was there.

There’s an alternative explanation. Saudi Aramco could never do anything but paint a bright future for oil consumption — but its revealed preference is more cautious. If it invests too aggressively now, it risks flooding a market that is gradually turning its back on petroleum, driving down prices and the kingdom’s own oil revenues. Its warning that oil supply will fall to about 80 million daily barrels in 2030 without more capex is pretty much in line with the levels of demand that BP expects at that point, in a world which manages to keep global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius.

Rather than being driven away from profit-maximizing activities by environmentalists and ESG rhetoric, investors in oil and gas are keeping their checkbooks closed because they see a future not of growth — but of decline, and fall. If Saudi Aramco believes differently, now is the perfect time for it to put its money where its mouth is.