German researcher unearths documents on new dinosaur species thought to have been destroyed during WWII

A new species of a predatory dinosaur that roamed North Africa 95 million years ago has been identified, nearly 80 years after its sole known specimen was destroyed during a World War II bombing raid. German researchers have stumbled upon previously unknown photographs of the lost fossil, enabling them to reevaluate its original classification and identify the species anew, Tameryraptor markgrafi.

In the summer of 1914, Austrian fossil collector Richard Markgraf unearthed the remains of a massive dinosaur in Egypt’s Bahariya Oasis. As an article by ZME Science documents, the fossils were shipped to Munich, where Ernst Stromer von Reichenbach studied them extensively. In 1931, Stromer identified the specimen as Carcharodontosaurus, or "shark-toothed lizard." Measuring over 10 meters in length, this predator rivaled the infamous Tyrannosaurus rex in size and ferocity.

However, the dinosaur's story took a tragic turn. By 1944, Europe was engulfed in World War II. During an Allied bombing raid in Munich, the Old Academy—home to Stromer’s collection—was destroyed, and the fossils were lost in the ensuing fire. For decades, all that remained were Stromer’s detailed notes, sketches, and a few photographs.

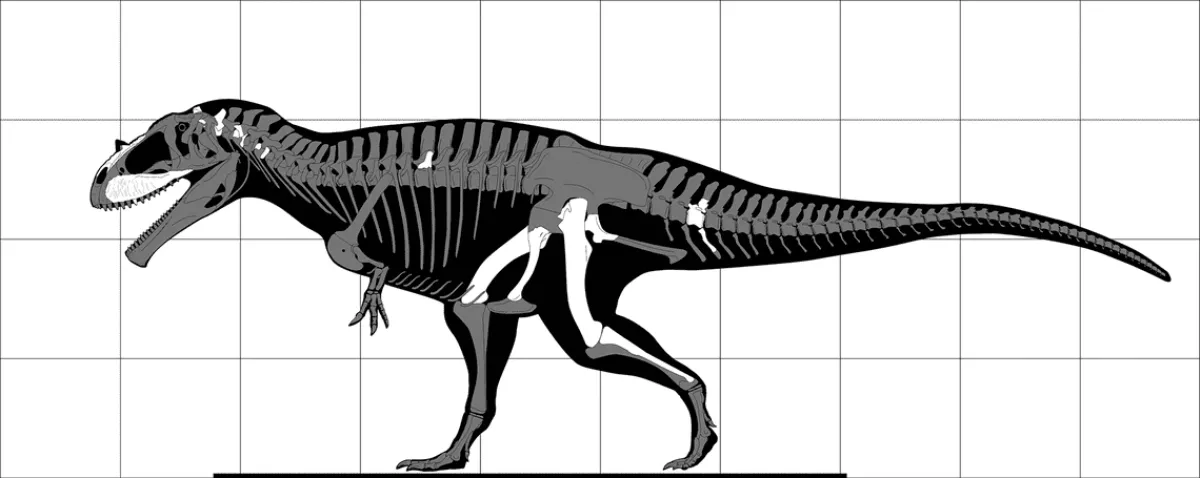

Nearly a century later, a remarkable discovery brought new life to this long-lost dinosaur. While conducting research, Maximilian Kellermann, a master’s student at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, stumbled upon a forgotten set of photographs in an archive. These historical images, taken by Stromer, captured the original skeleton in detail, including portions of the skull, spine, and hind limbs, preserved before their destruction. For paleontologists, the photographs were a time capsule offering invaluable insights.

“What we saw in the historical images surprised us all,” Kellermann shared. The research team, led by Kellermann, Professor Oliver Rauhut, and Dr. Elena Cuesta, carefully analyzed the photographs and made a groundbreaking discovery: the Egyptian dinosaur was not Carcharodontosaurus. Instead, it belonged to an entirely new species, which they named Tameryraptor markgrafi.

The name honors the ancient Egyptian term "Tamery," meaning "beloved land," and Markgraf, the fossil's original discoverer. Researchers believe this predator roamed Earth during the Cretaceous period, between 66 and 145 million years ago.

Estimated to have been about 10 meters long, Tameryraptor markgrafi was a formidable predator. Its teeth were designed for slicing through flesh, while a nasal horn added an intimidating flourish. The team also identified other unique anatomical features, such as braincase proportions and differences in the lacrimal bone, distinguishing it from Carcharodontosaurus. These findings suggest that the Egyptian and Moroccan theropods were not close relatives but distant cousins, with distinct evolutionary paths shaped by localized ecological pressures.

This discovery challenges previous assumptions about a uniform population of predators across North Africa. Instead, it points to greater diversity among dinosaur species in the region. “Presumably, the dinosaur fauna of North Africa was much more diverse than we previously thought,” Rauhut explained.

Carcharodontosaurids, to which both species belong, were among the dominant predators of the mid-Cretaceous period. They rivaled Tyrannosaurus rex in size and played a significant role in the ecosystems of Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent. However, the new findings suggest these predators were not as widespread or cosmopolitan as once believed.

The Limits of Historical Evidence

The study’s conclusions are inherently limited by the absence of the original fossils. The authors acknowledge this, noting that their interpretations rely heavily on Stromer’s photographs and cannot capture the full three-dimensional complexity of the bones. Features such as bone texture and finer anatomical details remain inaccessible, potentially constraining their analysis.

Nonetheless, the researchers utilized modern phylogenetic techniques and comparative data from related theropods to support their claims. They emphasized measurable traits, such as the distinctive nasal morphology, to bolster the case for Tameryraptor markgrafi as a unique species.

While cautious about their findings, the team believes their methodology is robust. Their analysis aligns with broader patterns seen in other carcharodontosaurids and contributes to a growing understanding of theropod diversity during the Cretaceous period. As they wrote, “While our analysis is inherently limited, the evidence strongly supports the distinctiveness of this taxon.”

This study highlights how even fossils destroyed by war can continue to provide valuable insights, thanks to the meticulous documentation of scientists like Stromer and the dedication of modern researchers. At the same time, it underscores the vast gaps in our knowledge about prehistoric life.

Even as the German team celebrate their findings, they are forthright about the work’s original roots. “Future discoveries may revise or even overturn our interpretations,” they write, serving as a reminder that science thrives on revision.

By Nazrin Sadigova