French colonialism and nuclear testing - Algeria and Polynesia are still waiting for justice Will Macron pay back the “debt”?

The Nuclear Age began in the mid-20th century against the backdrop of the collapse of empires. However, even as postcolonial states emerged from colonial rule, they continued to bear the burden of the devastating health and environmental consequences of colonizers' actions, such as nuclear weapons testing.

The toxic legacy of French nuclear weapons testing in North Africa and Polynesia is just one example of how nuclear testing disproportionately impacts the health and safety of indigenous peoples in the broad sense of the word.

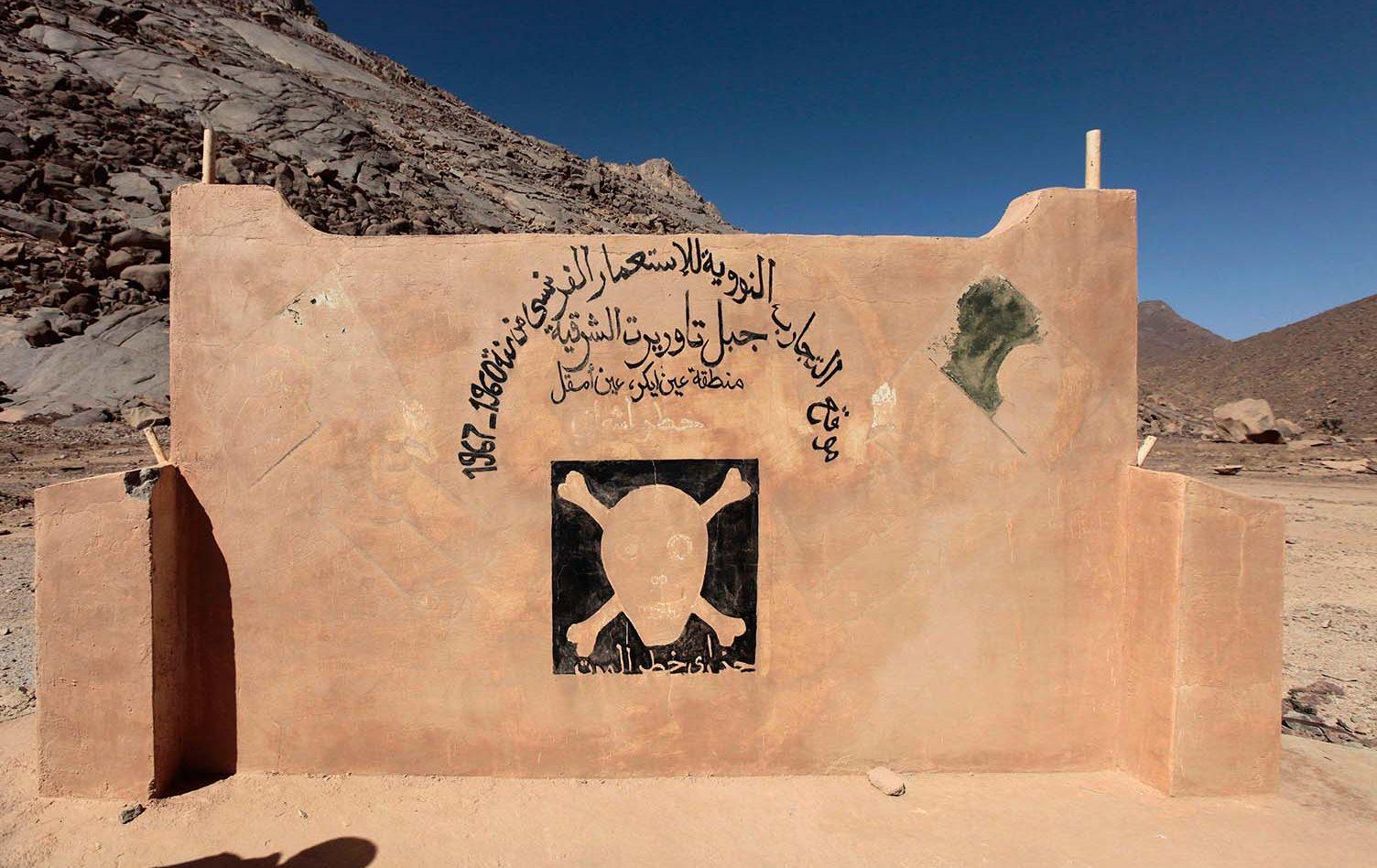

Tests in Algeria

Between 1960 and 1966, France conducted 17 nuclear tests in the Sahara in Algeria. The vast majority of these trials occurred after Algeria gained independence from France after more than eight years of struggle. The Evian Accords, which ended hostilities, gave France a five-year lease on Saharan testing sites they had previously used for testing - a concession that the Algerians had long been reluctant to make precisely because of the negative consequences for the health of the nation.

Many hundreds of military personnel, nuclear program workers, and the local Tuareg tribesmen were exposed to radioactivity as a direct result of nuclear testing. There were also high levels of radiation throughout the region, blamed on the radioactive fallout that blanketed the area during and after the tests. Elevated levels of radioactivity in the atmosphere were detected even in the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, 3,200 kilometers away from the testing sites.

The health and environmental consequences of these tests were compounded by the fact that for many decades, radiation levels and even the exact locations of these test sites remained classified. The local population had to deal with their consequences almost blindly, without even basic information about the nuclear threat they faced.

As Jill Jarvis, an American scientist from Yale University and a specialist in the Maghreb, notes, the impact of radiation from nuclear tests on the population of North Africa continues today. “Radioactive dust still comes from the Sahara, from those nuclear bombs, the consequences of which are incurable. In this sense, even the sand itself in the desert was colonized by France.”

In recent years, France has taken several timid steps to change the situation regarding the elimination of the consequences of the tests in Algeria. In 2010, the French government finally passed a law offering compensation to victims of nuclear testing. But as of 2021, only one of the 545 people receiving compensation was Algerian, the rest were from mainland France. The 2021 Stora report, aimed at promoting reconciliation between the two countries, did not recommend specific recovery actions, such as France's cleanup of the nuclear site.

Meanwhile, the fight for transparency over cleanup initiatives, as well as where radioactive materials are stored, continues in both Algeria and France, where NGOs are trying to influence the country's government on the issue.

Nuclear weapons testing in Polynesia

After Algeria gained independence in 1962 and nuclear testing there became increasingly problematic, Paris turned its attention to its remote ocean territory and isolated two uninhabited atolls in the Tuamotu group, Mururoa and Fangataufa.

Winiki Sage, president of the Economic, Social and Cultural Committee of French Polynesia, said that 20 years after the humiliation of World War II, and with the Cold War approaching a dangerous climax, France was seeking to ensure its own nuclear security through a containment policy modeled on the United States and THE USSR.

Mr Sage said that when the area was proposed as a testing site, there was some hesitant protest from the French Polynesian assembly and community members, but these protests soon died down as many were convinced that the tests would be safe and that significant the military buildup will bring economic benefits.

"We didn't understand what was happening," he said. “Many Tahitians and Polynesians fought for France during World War 2. And when the French officials came here and said, 'We're going to do some tests,' no one could have imagined that it would be so bad for us."

"All Tahitians were led to believe it would be safe," Mr Sage said. “I can tell you that at my grandmother’s house there was a beautiful photograph of a big nuclear bomb test and everyone thought it was something good. We didn't know it was anything bad for us."

In 1962, the Direction des Centers d'Experimentation Nucleaires (DIRCEN) oversaw the construction of observation posts, support bases, and other infrastructure for the program before the first explosion in 1966 - a plutonium bomb. codenamed Aldebaran, which was dropped from a helium balloon.

From this day on, France will conduct regular tests on the atoll. It should be noted that some of the explosions were nearly 200 times more powerful than the bombs dropped by the United States on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

Fifty years after the first nuclear test and 20 years after the last, Mururoa Atoll in French Polynesia is still largely a no-go zone.

But Mr Sage said the program and its intentions were shrouded in secrecy and little information was provided about the possible effects of radiation on the thousands of people who worked there, often wearing little more protection than shorts and T-shirts, on boats as well as a little 15 km from the test site. Scientists suggest that the main island of Polynesia, Tahiti, located at a distance of more than 1000 km, was also exposed to radiation.

“Thousands of people - thousands of Polynesians - worked there. All these people, some lived on outlying islands, all went to work for the military,” Mr. Sage said. “There were a lot of people there, they worked, ate, fished. Nobody realized that it was very, very dangerous."

Under pressure from scientists and the public, the United States, Great Britain, and then the Soviet Union abandoned nuclear testing in 1963, but the French continued to do so until the mid-1970s, when they moved to regular underground testing on atolls with sensitive ecosystems.

Eventually, France was forced to declare a moratorium on nuclear testing, but it was lifted in 1995 only so that France could test a new warhead for submarines. The decision was regretted and condemned by Australia, New Zealand, Japan, other Pacific countries, and many of France's European allies. In French Polynesia, the decision angered many Tahitians, and riots in the capital Papeete caused millions of dollars in damage and led to the burning of the capital's airport terminal. France had to stop nuclear testing in the Pacific Ocean in 1996 under pressure from the public and the international community.

For years, the French Ministry of Defense insisted that the tests caused no harm to the environment and that workers' health was not at risk. But Richard Tuheyawa, a member of the French Polynesian Assembly, said the consequences were clear.

The environmental impact was also worse than France had previously assumed. The soil around the atoll remains highly radioactive today, and there are fears that the atolls were weakened by the explosions and could collapse, causing a tidal wave.

Despite mounting evidence, the French government denied all suggestions that nuclear testing was harmful to health until 2010, when it introduced a compensation program for radiation victims.

In 2021, during his visit to Polynesia, shortly before the 2022 presidential elections, Macron concluded his visit with a speech in which he declared a "debt" to French Polynesia for the tests. Who will pay off this debt and when remains in question.

Former colonial powers around the world have cemented their claims to global political influence with their nuclear weapons. A true end to the ongoing effects of colonialism must mean not only the abolition of nuclear weapons but also the restoration of justice to those affected by its existence. The toxic legacies of the nuclear race and colonialism are deeply interconnected, and they must be addressed comprehensively and without delay.