Spain and the collapse of the European dream Life beyond the postcards

The end of the year is traditionally a time to reflect. For me, the past year brought a personal realization: the myth that life in European countries is “all okay and very good,” as an old popular song once claimed, doesn’t hold up. Living in Spain for several months made me see firsthand that reality often falls far short of the expectations shaped by clichés and stereotypes.

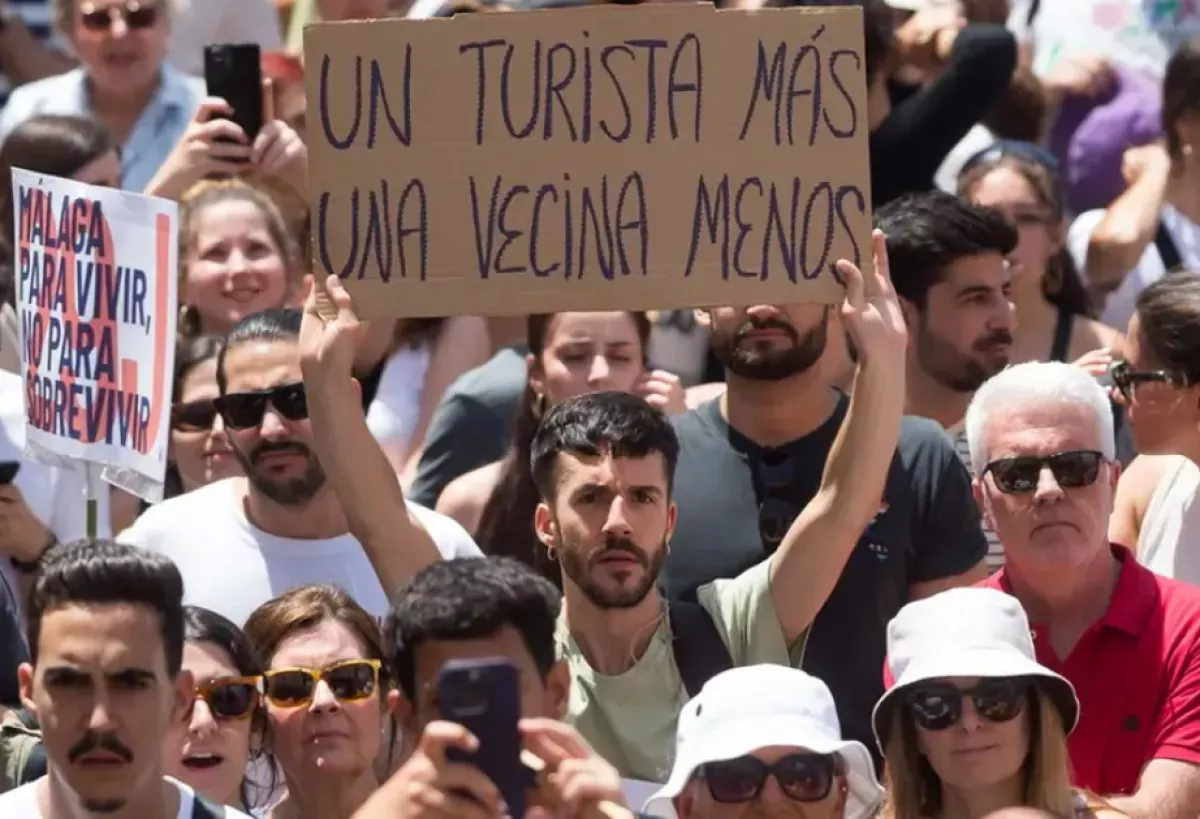

This country is great for tourism. In the first half of 2025, Spain broke records for the number of visitors. According to the National Statistics Institute (INE), 44.5 million people visited the country during this period—a 4.7 per cent increase over the previous record. Tourists spent €59.622 billion in Spain, another historic high. Clearly, by the end of the year, these figures are likely to look even more impressive.

But do these numbers indicate that the country is experiencing an economic boom? Not at all. Spain is not heading toward a market crash—it is moving toward a full-blown housing crisis. Experts warn about the growing gap between household incomes and the cost of buying or renting property. Rising prices and housing shortages are making home ownership—and even long-term rental—unattainable for an increasing number of families.

This is not a classic “bubble” set to burst with falling prices, but rather a situation in which the market appears stable on paper, yet people are physically unable to enter it. Real estate experts note that more and more Spaniards find themselves unable to afford either mortgages or rental rates. Prices are rising faster than incomes, especially in major cities and tourist areas.

One of the key problems is a structural housing deficit: specialists estimate that Spain lacks over a million apartments to meet both current and accumulated demand. Incomplete construction, bureaucracy, lengthy licensing procedures, and weak policies to promote affordable housing only worsen the situation.

Experts warn that 2026 could bring new record prices in the real estate market. If the trend continues, finding housing—whether to buy or rent—will become even more difficult, particularly for young families and the middle class.

Against this backdrop, another striking fact emerges: 25 per cent of housing in Spain lacks heating. A study by the portal Idealista revealed a serious infrastructure gap in the country’s housing stock. In the northern provinces—Navarre, Soria, and Salamanca—up to 96 per cent of homes have heating, which is essential during harsh winters.

In contrast, the situation in the south and on the Canary Islands is the opposite: 86–89 per cent of properties in Tenerife and Las Palmas have no heating, and in Cádiz and Huelva, this figure reaches 54 per cent. Madrid leads the country, with only 5 per cent of homes lacking heating systems, while in Barcelona, the number rises to 17 per cent, exacerbating humidity problems during winter.

In coastal areas such as Valencia, Alicante, and Barcelona, the absence of heating often leads to mold, which in turn reduces rental values.

There is another, highly significant demographic indicator. According to Spain’s National Institute of Statistics (INE), as of July 1, 2025, the country’s population reached 49.3 million—a historic high. However, most of this growth comes from migration rather than natural population increase. As a result, the number of native Spaniards is declining, with the influx of migrants merely offsetting the demographic loss.

One problem inevitably leads to another. Demographic studies show a significant decline in the young population aged 20–39—a 36.8 per cent drop over the past 20 years. This means millions of working-age people are either leaving the country or postponing starting families. As a result, one of Spain’s most pressing challenges is the rapid aging of its population.

Reports from analytical agencies indicate that in the coming years, Spain will face one of the most severe demographic imbalances in Europe: for every 100 people retiring, there will be only 74 young workers available to replace them in the labor market. This threatens the sustainability of the pension system and increases the burden on the budget and social services, particularly healthcare, which is already under serious strain.

Against this backdrop, Spain’s overall unemployment rate stands at around 10.4–10.9 per cent, one of the highest in the European Union. Youth unemployment among those under 25 reaches 25–26 per cent, more than double the EU average. These figures reflect not only difficulties in finding work but also the deep economic deadlock faced by many young Spaniards, who are often forced to seek employment abroad.

In 2025, the average gross salary is approximately €1,800–€1,900 per month, leaving about €1,450–€1,550 after taxes. For an EU country, this is, to put it mildly, modest. Spain’s minimum wage is €1,184 per month, received by roughly three million people. These numbers clearly illustrate the challenges of everyday life for the average Spaniard.

Adapting to life in Spain is even more challenging for foreigners planning to move permanently. Learning Spanish—and, in some regions, local languages such as Catalan, Basque, or Galician—is the minimum requirement for integration. Even then, finding work in a context of high unemployment and relatively low salaries can be a serious challenge, especially for those without specialized or in-demand skills.

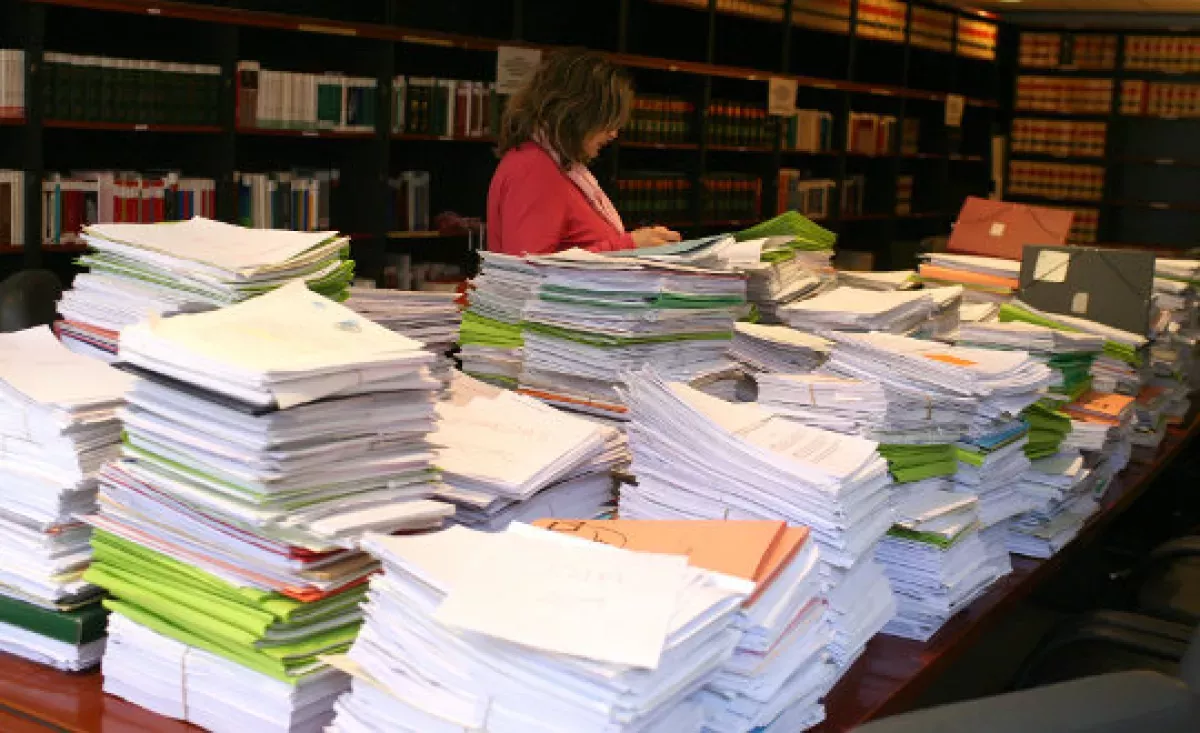

Spanish bureaucracy deserves special attention—it is a massive and systemic problem. Long waits for applications to be processed in government offices, protracted procedures for registration, obtaining documents (especially for foreigners), securing residence permits, handling tax matters, or exchanging driver’s licenses have become the norm. For citizens of Azerbaijan, accustomed to the efficiency of ASAN service, navigating Spanish bureaucracy can easily turn into a nightmare.

The same challenges apply to Ukrainian citizens who moved to Spain because of the war. Ukrainians—and many other foreigners—are often shocked by the remarkably slow pace of the Spanish banking system. Queues and delays for services, from opening an account to obtaining credit, frequently stretch for weeks, and sometimes even longer.

Spain’s healthcare system (Sistema Nacional de Salud) is no less problematic, known for its chronic slowness. The average wait to see a general practitioner is around nine days. Appointments with a specialist often take more than four months—about 140 days from the referral. The average wait for planned surgery is roughly 126 days, and nearly one in four patients must wait more than six months.

These figures vividly illustrate the deep systemic problems in Spanish healthcare, stemming from underfunding, staff shortages, and significant regional disparities. Yet, this is only part of the overall picture.

Clearly, everyday life in Spain is far from the idealized image of European prosperity. The demographic crisis, an aging population, months-long waits in the healthcare system, cumbersome and slow bureaucracy, high youth unemployment, and wages that often fall short of covering real expenses all create serious obstacles to a stable and comfortable life.

For those dreaming of a “European paradise,” living in Spain often turns out to be far more challenging than it appears from the outside. I say this as someone who has seen Spain with my own eyes.