Who is losing out in Sweden's cashless society?

Bank cards and mobile apps have become the standard payment methods across most of the world, but nowhere is the shift away from cash more evident than in Sweden, which is on course to become a cashless economy. The Bank of Sweden has noted that the amount of cash in circulation has halved since 2007, with many businesses and public services no longer accepting cash payments. However, for a significant number of people, the cashless transition has made life much more difficult.

Research has revealed, that certain vulnerable groups, particularly those living in poverty, are disproportionately affected by Sweden’s cashless society. An article by The Conversation publication highlights that these individuals often lack access to banking services or cannot afford digital technology, making them heavily reliant on cash. Some of the people interviewed for the research included homeless individuals, people with mental health issues, and those with low incomes.

The trend to abandoning cash is partially driven by a Swedish law that emphasizes “freedom of contract,” meaning that accepting cash is not mandatory for businesses, including banks. As a result, cash usage has rapidly declined, particularly in public transport, stores, and services, where digital payments have become the standard.

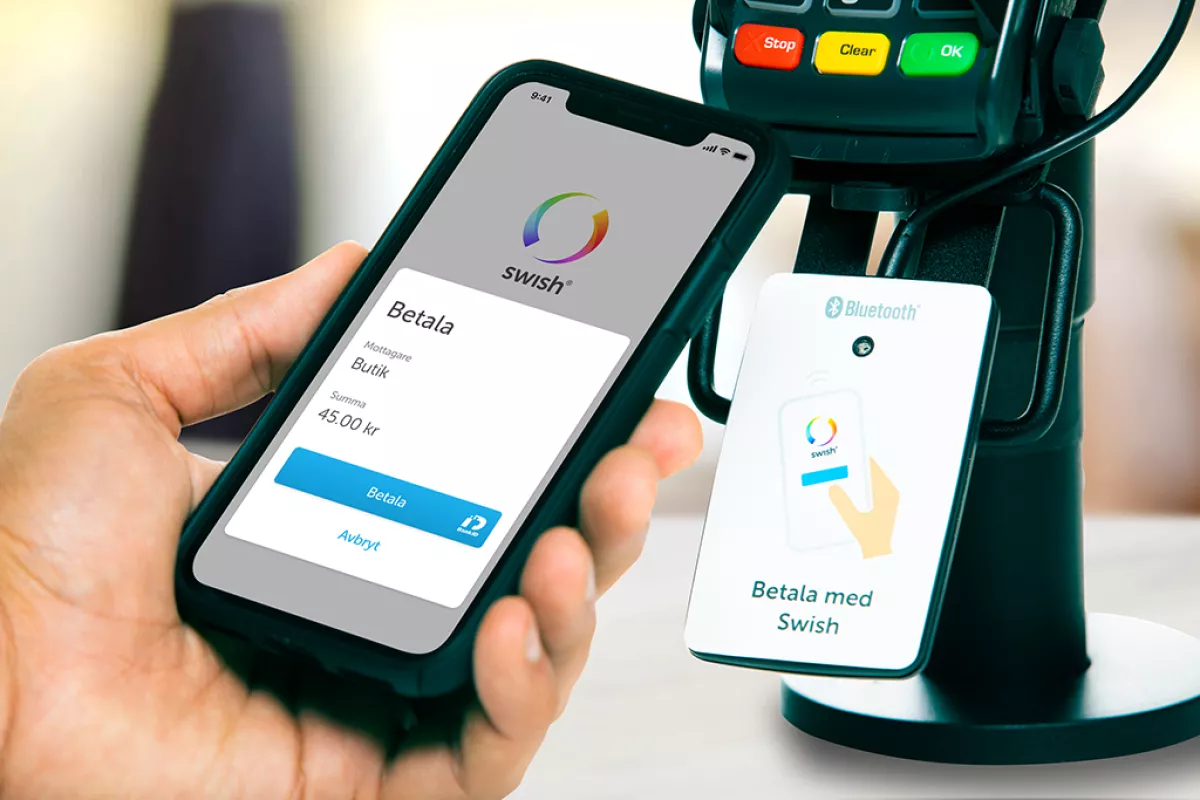

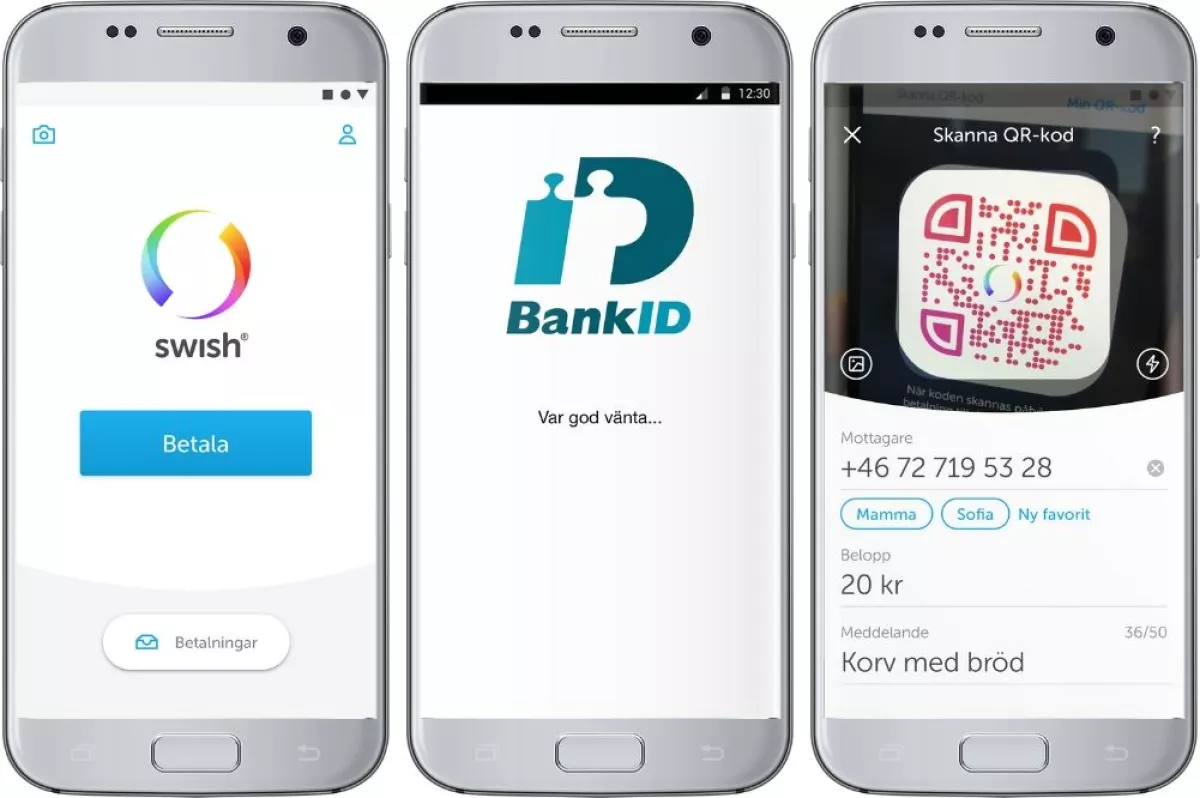

The movement away from cash was significantly accelerated by the launch of Swish in 2012, a mobile payment app created by a group of Swedish banks. By 2017, Sweden was using far less cash than other European nations, and today, more than 80% of the Swedish population uses Swish. For the majority of Swedes, living in a cashless society is efficient and convenient, provided they have access to a bank account and the necessary technology.

For vulnerable groups, navigating a predominantly cashless economy presents not just practical challenges but also emotional and social obstacles. These individuals often feel excluded from mainstream society, stigmatized, and dehumanized as they struggle to participate in everyday life.

Being cash-dependent in Sweden often results in living within what researchers refer to as "cash bubbles," where people can only use cash in certain settings, such as buying basic necessities or visiting small, cash-accepting cafes. However, they are unable to pay for services like parking or bills without assistance. Volunteers in community groups often have to step in to handle banking tasks for those who are unbanked. Ukrainian refugees without a bank account, for example, are struggling to pay bills, and homeless individuals without smartphones or bank accounts are forced to rely on others to pay for parking, often at a marked-up cost.

The article also points to the emotional toll this transition takes on cash-dependent individuals. One interviewee, a woman who had saved up to buy her grandchild a gift, shared her experience of being humiliated at the checkout when the store refused to accept her cash. Such experiences of exclusion, shame, and frustration underscore the emotional impact of the country’s cashless transition.

Sweden’s transition toward a cashless economy is seen as a symbol of the country’s embrace of technological advancements. The nation has a history of being early adopters of new technologies, and business researchers predicted that cash would be obsolete in Sweden by 2023. While the article acknowledges that this prediction hasn't fully come to fruition, the shift is certainly well underway. The Swedish economy has evolved significantly over the past 150 years, with technological innovation playing a major role in its transformation from poverty to one of Europe’s richest countries.

The Swedish banking system plays a central role in this cashless transition. In addition to Swish, banks in Sweden also provide the electronic IDs required to access public services such as the tax authority, as well as benefits related to illness, disability, and unemployment. Consequently, individuals without bank accounts are unable to access these crucial services, further entrenching their marginalization.

The COVID-19 pandemic further reinforced the shift away from cash, as fears of physical money spreading contamination made it seem unsanitary. Cash began to be viewed negatively, associated with dirt and crime, while digital transactions gained favor as clean, modern, and safe.

For those who still rely on cash, the stigma associated with it exacerbates their sense of exclusion. According to the article, cash is increasingly seen as a relic, and in Sweden’s digital-first society, people who are unbanked or digitally excluded face not only practical challenges but also profound emotional isolation.

Sweden's rapid digitization of society has led to a sense of disconnection, with some interviewees expressing that they feel like robots, interacting with technology instead of with other people. For those left behind by this digital shift, the transition to a cashless society is not just a matter of financial accessibility but also of social and emotional well-being.

By Nazrin Sadigova