The Balkans and European-style hegemony A quest for dominance amid global rivalries

In recent years, the Balkan direction has become a top priority for the European Union. Brussels’ actions are marked by assertiveness and aggressiveness, and it seems that European diplomats no longer intend to restrain themselves within any limits. Their primary objectives are to push competitors—primarily Türkiye, Russia, and China—out of the peninsula and to establish full hegemony in the region.

This surge of activity is largely driven by global upheavals. The arrival of the Republican administration in the United States and the active diplomacy of President Donald Trump have forced European politicians to reconsider their real place in the new world order.

The U.S. demands that its partners open their markets to American companies and increase defence spending within the NATO framework. At the same time, Trump consistently emphasises their subordinate position.

Under these circumstances, Brussels faces a pressing question of how to ensure its strategic autonomy. However, a major obstacle to this goal is the EU’s limited access to natural resources and cheap energy sources. After relations between Europe and Russia were severed, one of the nearest potential suppliers of energy became the Middle East and the Persian Gulf region — access to which lies through the Balkan Peninsula.

To some extent, the situation resembles that of the early 20th century, when Imperial Germany began constructing the Berlin–Istanbul–Baghdad railway to reach oil-rich regions.

Yet, the path of European expansion is obstructed by the interests of other powers that also have their own priorities in the Balkans. Of particular concern to Europeans is Türkiye’s growing influence. The Balkans serve as Ankara’s economic gateway to Europe. In 2024, the Balkan Investment Forum was held in Edirne, where the Turkish side set a goal to increase trade turnover with the countries of the region to $40 billion by 2025. Moreover, Türkiye pays special attention to local Muslim communities. Numerous non-profit organisations have been established to promote Turkish influence.

Turkish military personnel take part in the NATO-led International Forces in Kosovo (KFOR), while civilian officials are represented in UN missions.

In May 2025, a conference of the chiefs of general staff of the Balkan countries was held in Istanbul, and earlier, special forces exercises involving regional states took place in Türkiye. Ankara declares its commitment to the principles of multi-ethnicity, multiculturalism, and multiconfessionalism. However, within the EU, Turkish initiatives are viewed as an attempt to expand its influence.

Another rival of the West is Russia, which is actively expanding its presence in the energy sector. Russian companies hold shares in gas distribution networks and storage facilities. Through this economic expansion, Russia has gained control over key assets of Serbia’s gas infrastructure: Gazprom owns 51% of the country’s only gas storage facility, Banatski Dvor, and 50% of the distribution company Yugorosgaz, which also controls around 4% of Serbia’s gas transmission network.

Despite the EU’s policy of diversification, Russia continues to strengthen its energy positions through direct investments in gas transportation infrastructure. A key project in this regard is the Balkan Stream (the Serbian section of the TurkStream pipeline), which, completed in 2021 under Gazprom’s supervision, not only ensured additional gas supplies but also created a serious structural barrier to the EU’s efforts to reduce the region’s dependence on Russian energy. Brussels views this project as a tool for Moscow to preserve its geopolitical influence in the Balkans.

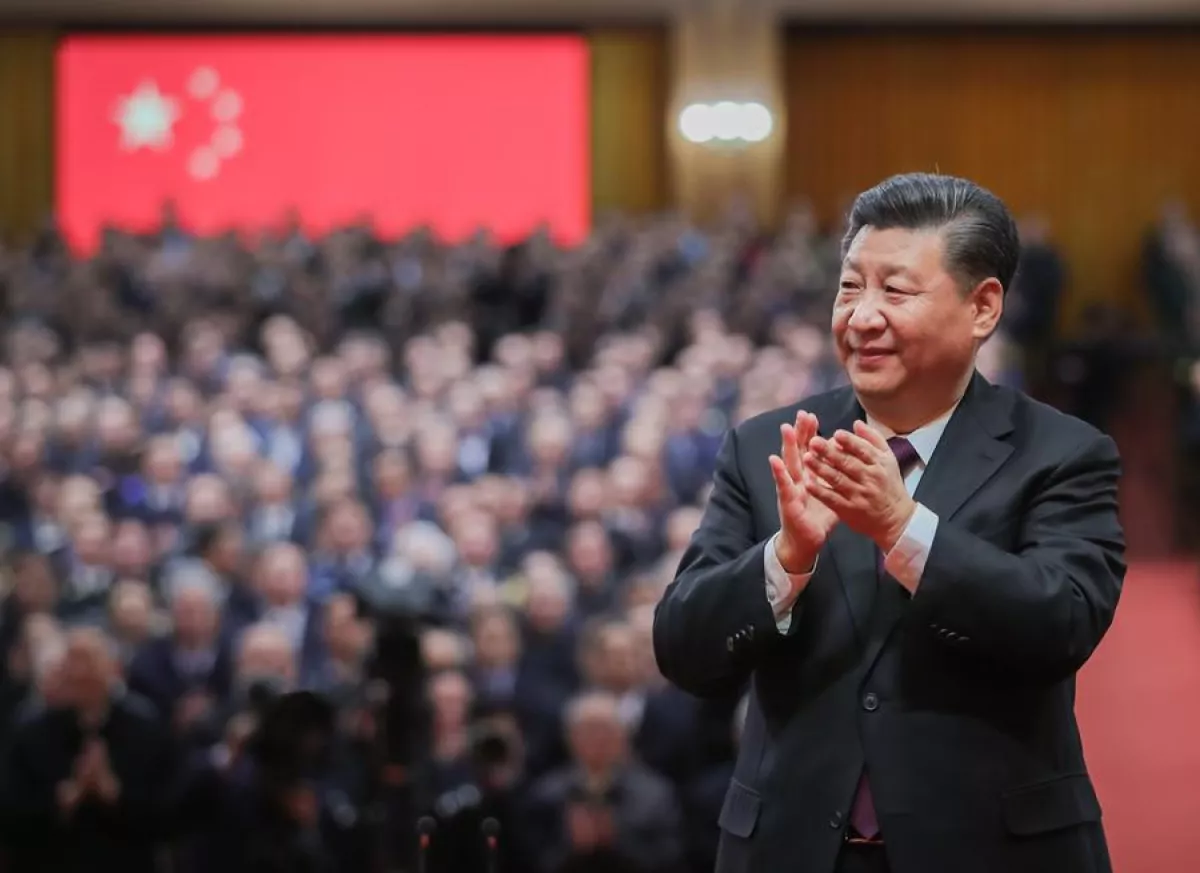

Another competitor of the EU in the Balkans is China. All the countries of the region have joined Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative through regulatory mechanisms — specifically, memoranda of understanding.

Beijing has also managed to establish an institutional framework for cooperation with Central and Eastern European countries — the “14+1” format. Chinese projects, particularly in transport and logistics, serve as alternatives to European initiatives.

The activity of these competitors has forced Brussels to accelerate its own expansion in the Balkans — first and foremost through strengthening its military presence in the region. Since 2023, the NATO mission in Kosovo has grown from 4,000 to 4,500 troops. Similar measures have been taken in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the European military contingent has increased from 600 to 1,100 soldiers, with plans to expand it further to 1,500 personnel.

Europe is also continuing its policy of economic absorption of the region. To achieve this, the Balkan states are being offered the traditional “carrot” — eventual membership in the European Union. This process is proposed to unfold in two stages.

At the first stage, each country in the region that meets the necessary requirements will be able to join the single market, similar to how Finland, Sweden, and Austria did in 1994. For the Balkans, this level of integration is expected to be achieved by 2030. In this way, European goods, capital, and services will gain unrestricted access to Balkan markets, in exchange for cheap labour. At the second stage, the legal systems of the Balkan states are to be aligned with “European standards” and subordinated to Brussels.

Meanwhile, European experts note that the prospect of joining the European Union — which for many years motivated local elites to pursue a pro-European political course — has now reached a dead end. Currently, only two countries in the region — Serbia and Montenegro — are engaged in accession negotiations. Albania and North Macedonia have been waiting for years to begin their integration process, while Bosnia and Herzegovina is still not even an official candidate for EU membership.

An important step in strengthening European influence in the region is the replacement of local elites with more manageable figures. A clear example of this can be seen in the protests in Serbia, which, according to local authorities, are financed by European non-governmental organisations. According to Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, unnamed states have spent around €4 billion to destabilise Serbia. Experts note that Brussels is dissatisfied with the current Serbian leadership, which maintains overly close relations with Istanbul, Moscow, and Beijing.

In 2021, the German diplomat Christian Schmidt was appointed as the High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina at Germany’s initiative — without an appropriate resolution from the UN Security Council. This decision provoked discontent from China and Russia, yet it did not prevent the new High Representative from taking office and beginning a purge of the republic’s political structure from opponents of the EU.

In conclusion, it can be noted that in consolidating its control over the Balkans, Brussels employs three of its traditional tactics: promoting the prospect of EU membership, replacing undesirable regimes with more compliant ones, and applying military pressure. The economic crisis in Europe and the need to secure access to Middle Eastern energy resources are pushing Brussels to intensify its expansionist policy. However, on this path, Europeans will have to confront other global players — primarily Türkiye, China, and Russia.