Why one of world’s top energy producer at risk of facing energy crisis

In the state with the fourth-largest proven reserves of oil and gas in the US, there is a looming energy shortage.

Above the Arctic Circle, Alaska’s North Slope produces around 465,000 barrels of crude oil daily, shipped south for refining and export. Yet in south-central Alaska, home to 63% of the population and Anchorage, utilities warn they may soon lack enough natural gas to meet heating and power needs.

A professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage who studies the economics of natural resources released an article on the issue through The Conversation publication.

Alaska’s North Slope holds about 990 billion cubic metres of proven reserves—almost equal to total US production in 2023—with an additional 5.66 trillion cubic metres potentially undiscovered. Technological advances could unlock up to 16.7 trillion cubic metres, according to the state-owned Alaska Gasline Development Corp. (AGDC).

Logistical nightmare

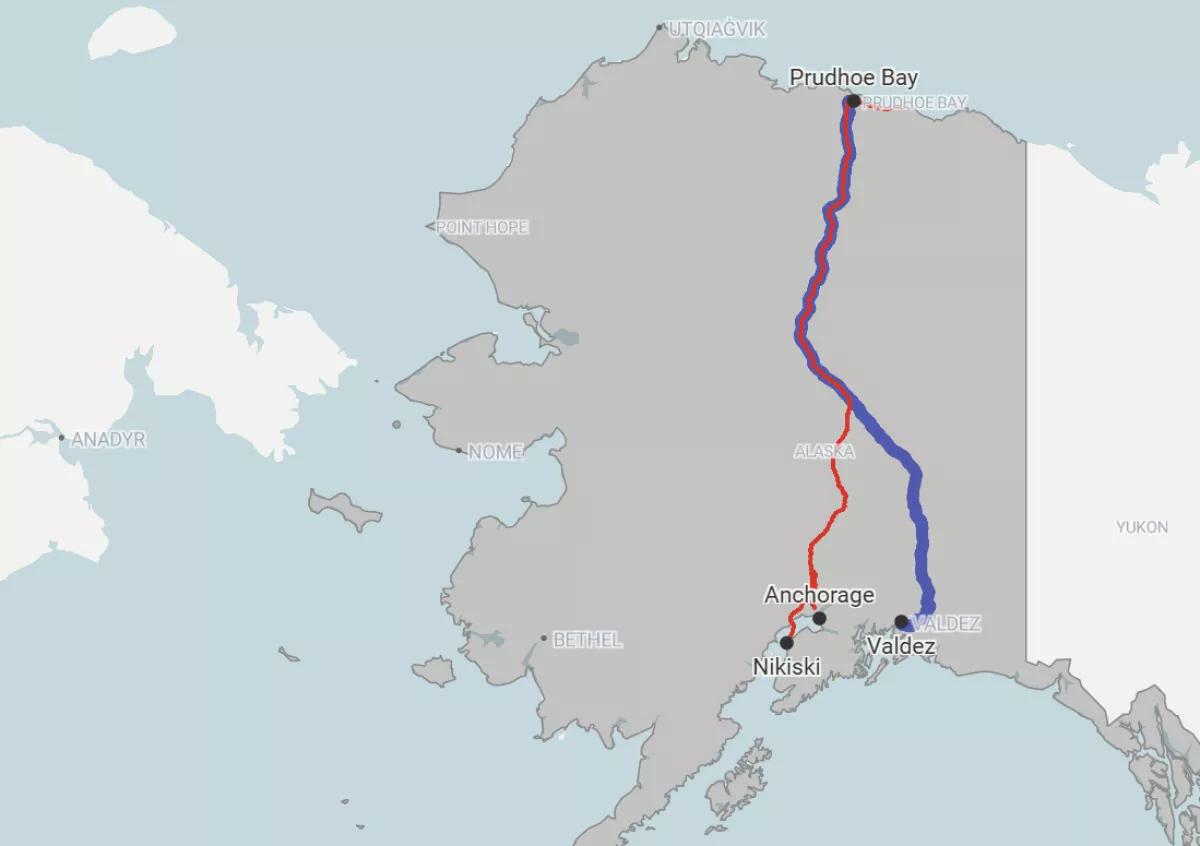

At its peak in the 1980s, the North Slope produced nearly 2 million barrels of oil per day, all moved through the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline to Valdez. But the pipeline was built for oil, not natural gas.

State law prohibits flaring excess gas, so producers reinject it into the ground to maintain pressure and boost oil output.

For decades, multiple gas development plans have failed despite hundreds of millions spent. The leading proposal today comes from AGDC: an $44 billion project (likely higher now) including a treatment plant on the North Slope, an 807-mile pipeline, and a liquefaction facility near Anchorage capable of exporting 20 million tons of LNG annually.

Meanwhile, south-central Alaska depends on natural gas for over 70% of its heating and electricity. Cook Inlet reserves, which have powered the region since the 1960s, are depleting, causing prices to soar. Wholesale gas prices rose from $132.84 per 1,000 cubic metres in 2005 to $309.63 in 2024, while US prices overall have halved thanks to fracking.

Alaska faces two costly options: build a pipeline from the North Slope or import LNG.

The pipeline could meet local demand and enable exports, though revenue hinges on global prices and competitiveness. Delays from financial, legal, or environmental hurdles would escalate costs. If successful, it could lower local prices to $78.96 per 1,000 cubic metres—a 75% drop from current rates and well below 2005 levels—boosting the regional economy.

Importing LNG is far more expensive. A legislative study estimates imported gas would cost $485.32 per 1,000 cubic metres—60% higher than current prices—burdening households and businesses already paying above-average US energy costs.

Beyond economics, Alaska faces a symbolic dilemma: could a state synonymous with energy production become an importer? For many, this paradox feels as jarring as Hawaii importing pineapples or New Mexico importing green chiles.

Alaska’s struggle mirrors a broader US debate between local energy self-sufficiency and economic efficiency. Texas, for instance, leads in oil production yet imports crude due to refining limitations.

As energy systems become increasingly globalized, local independence often comes with high costs. For Alaska, the question remains: invest billions to maintain energy independence—or embrace global markets for potentially cheaper, though less symbolic, supply?

By Nazrin Sadigova