Ultrasound opens door to surgery-free cancer treatments

Ultrasound, long a staple of medical imaging, is now emerging as a tool to treat cancer without surgery.

A discovery decades in the making could transform oncology by offering non-invasive ways to destroy tumours, BBC reports.

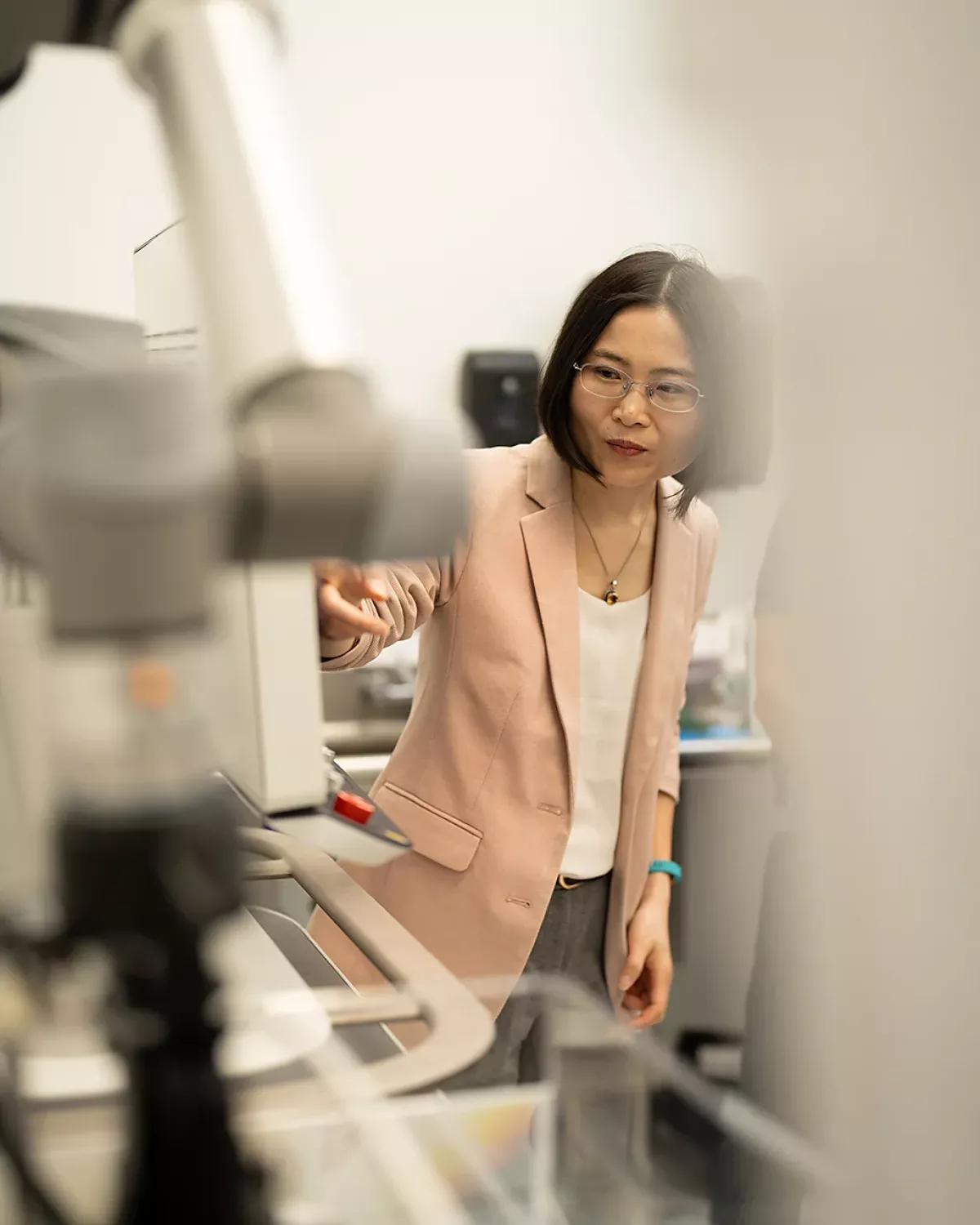

Zhen Xu, a biomedical engineering PhD student at the University of Michigan in the early 2000s, stumbled upon a method to break up diseased tissue using high-frequency sound waves.

While testing ultrasound on pig hearts, she accidentally increased the number of pulses per second to avoid disturbing lab colleagues. To her surprise, this not only reduced the noise but also tore apart living tissue almost instantly.

Xu’s serendipitous discovery became the basis for histotripsy, a technique now approved by the US FDA for liver tumours and recently adopted by the UK’s NHS under a pilot programme.

Histotripsy uses focused ultrasound bursts to create microbubbles that expand and collapse within tumour tissue, physically breaking it apart. Guided by a robotic arm, the device targets tumours with millimetre precision.

Procedures are typically completed in one to three hours, often in a single session, allowing patients to go home the same day. Side effects are uncommon, though complications such as abdominal pain or internal bleeding are possible.

While histotripsy shows promise, limitations remain. It cannot treat tumours shielded by bone or located in gas-filled organs like the lungs. Long-term data on cancer recurrence is still limited, and its effectiveness against other tumour types, including kidney and pancreatic cancers, is under study.

Histotripsy is part of a broader movement exploring ultrasound-based cancer treatments. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU), an older technology, destroys tumours by heating tissue. It has shown effectiveness in prostate cancer with faster recovery than surgery, though its heat can damage nearby healthy tissue.

Researchers are also exploring combining ultrasound with drugs and immunotherapy. Stimulating microbubbles in the bloodstream can open the blood-brain barrier, allowing chemotherapy to reach tumours more effectively.

Ultrasound may also enhance radiation therapy and make tumours more visible to the immune system, potentially allowing smaller doses of toxic treatments. In theory, targeting one tumour could trigger immune responses against others elsewhere in the body, though trials are still in early stages.

“Ultrasound isn’t a magic cure,” Xu cautions. “But it may spare patients unnecessary suffering while improving cancer treatment outcomes.”

As histotripsy and other focused ultrasound technologies advance, non-invasive cancer care is moving from experimental to practical, offering hope for treatments that are faster, safer, and less debilitating than traditional methods.

By Aghakazim Guliyev