Japanese scientist tests "unconventional" treatment for respiratory failures

A Japanese doctor and stem cell biologist has put his sights on developing a rather unorthodox treatment to help patients experiencing a respiratory emergency, which even won him the satirical "Ig Nobel Prize."

Is it possible to use the intestines for breathing when the lungs fail? His research on animals suggested that it might be, which encouraged Takanori Takebe to take his treatment dubbed "butt breathing" to human trials, as Science News reports.

Takanori Takebe serves as Director of Commercial Innovation at the Center for Stem Cell & Organoid Medicine (CuSTOM) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. As a physician and biologist specializing in stem cells, he spends much of his time developing lab-grown livers to treat organ failure.

Inspiration struck when a graduate student brought a book into Takebe’s lab describing how different animals obtain oxygen through their skin, reproductive organs, or even their guts. A few years ago, he became particularly fascinated by mudfish from the Umbridae family. When trapped in oxygen-poor waters, these fish supplement gill breathing by gulping air at the water’s surface and channelling it directly into their intestines.

“There are many diseases that can become life-threatening because they impair the lungs’ ability to transfer oxygen into the blood,” Takebe explains in Cincinnati Children’s online publication.

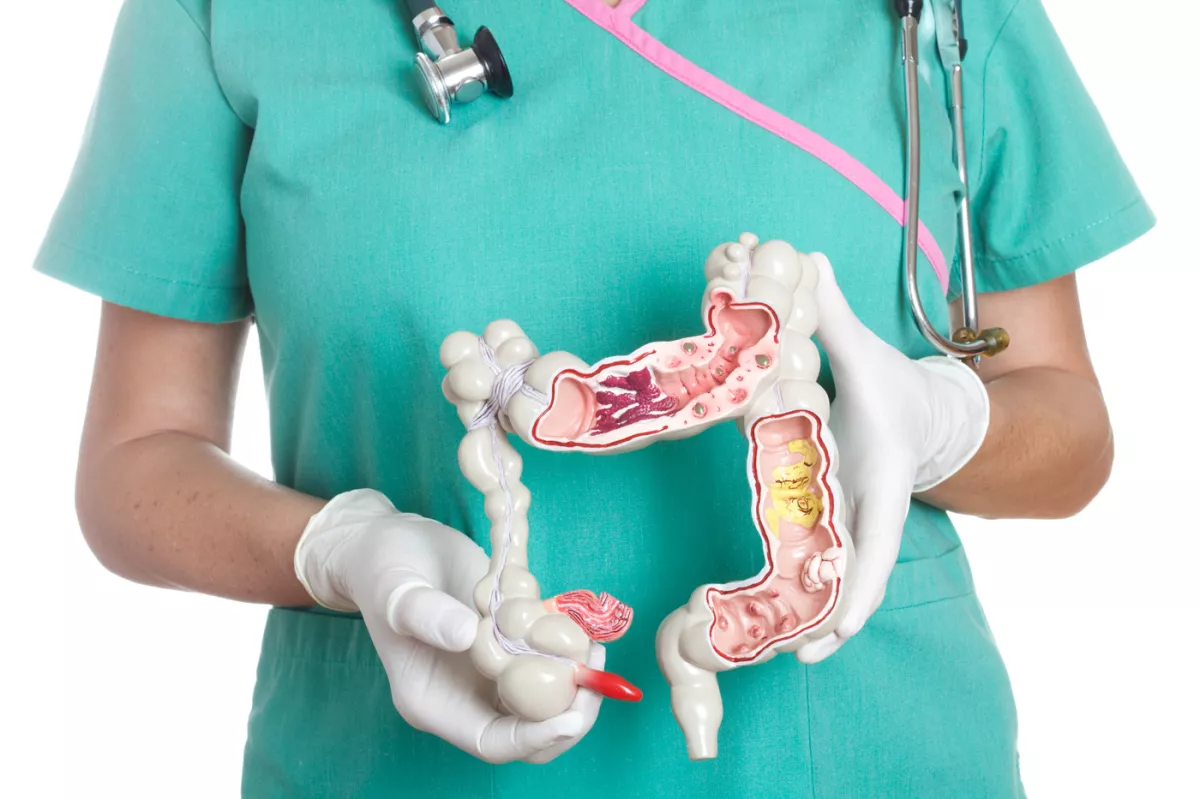

With his background in gastroenterology, Takebe knew the human intestinal tract is rich in blood vessels, which is why enemas can deliver medication directly into the bloodstream. He began to suspect that oxygen might be able to pass from the intestines into the blood as well.

Takebe’s interest in this unusual idea deepened several years ago, when his father came down with pneumonia and had to be placed on a ventilator. “I was really shocked by how invasive it is,” Takebe says. Knowing his father had already lost part of a lung to an earlier infection, he feared what would happen if the ventilator proved insufficient. That worry led him to explore whether oxygen could enter the body without using the lungs at all.

The Japanese medic and his colleagues developed an enema-like treatment using a liquid called perfluorodecalin, already used in some medical procedures. The liquid can be saturated with oxygen. Once inside the body, it releases that oxygen while its chemical structure opens up space to absorb “exhaled” carbon dioxide.

In experiments with mice and pigs, enemas containing this oxygen-rich liquid helped the animals survive prolonged low-oxygen conditions, which can be brought upon in cases such as airway injuries or inflammation, pneumonia — in which the lungs fill with fluid — and more. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients died simply because ventilators were unavailable.

“Further confirmation is needed, but our early studies show that our ventilation system can support patients with severe respiratory failure,” he notes.

The team published its findings in Med in 2021. Further pig studies published in 2023 showed that the technique could elevate oxygen levels for up to 30 minutes.

Takebe vividly recalls seeing pig blood samples shift from a muddy, oxygen-poor color to a bright, oxygen-rich red. “That was my aha moment,” he says — clear evidence that the concept might actually work.

In 2024, the work received an Ig Nobel Prize — a humorous award honouring research that first makes people laugh, then think. “Thank you so much for believing in the potential of [the] anus,” Takebe said at the ceremony.

The team has now carried out early safety tests in humans. Twenty-seven healthy male volunteers in Japan received doses of non-oxygenated perfluorodecalin.

The unorthodox technique has also attracted sceptics among pulmonologists. Some specialists argue that even if the intestines can absorb oxygen, sustaining life would require repeated enemas — an impractical and uncomfortable solution. They insist that researchers should focus on improving ways to support the lungs rather than relying on other organs to take over their function.

But others are more curious than critical. Kevin Gibbs, a pulmonary and critical-care physician at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, says the idea surprised him. “It definitely raised my eyebrows,” he says. “As someone who treats a lot of people who have low oxygen levels, I tend to think of myself as an above-the-waist doctor.” Still, if rectal oxygen delivery proves effective, it might become a useful tool in certain cases, he notes.

By Nazrin Sadigova