Terrorism trial over 9/11 conspirators remains in legal limbo 24 years after tragedy

As the world marked the 24th anniversary of the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States (commonly just referred to as 9/11) this week, the criminal case tied to the tragedy remains mired in legal limbo more than two decades later — with many doubting it will ever go to trial. The accused men have been held at the US military prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, while thousands of 9/11 families are left waiting for resolution.

More than 3,000 people were killed in the 2001 attacks across three locations, yet no one has been criminally convicted. According to reporting by PBS, one key factor at the heart of the delay lies in the methods US authorities used to obtain confessions from suspects.

Will death penalty remain on the table?

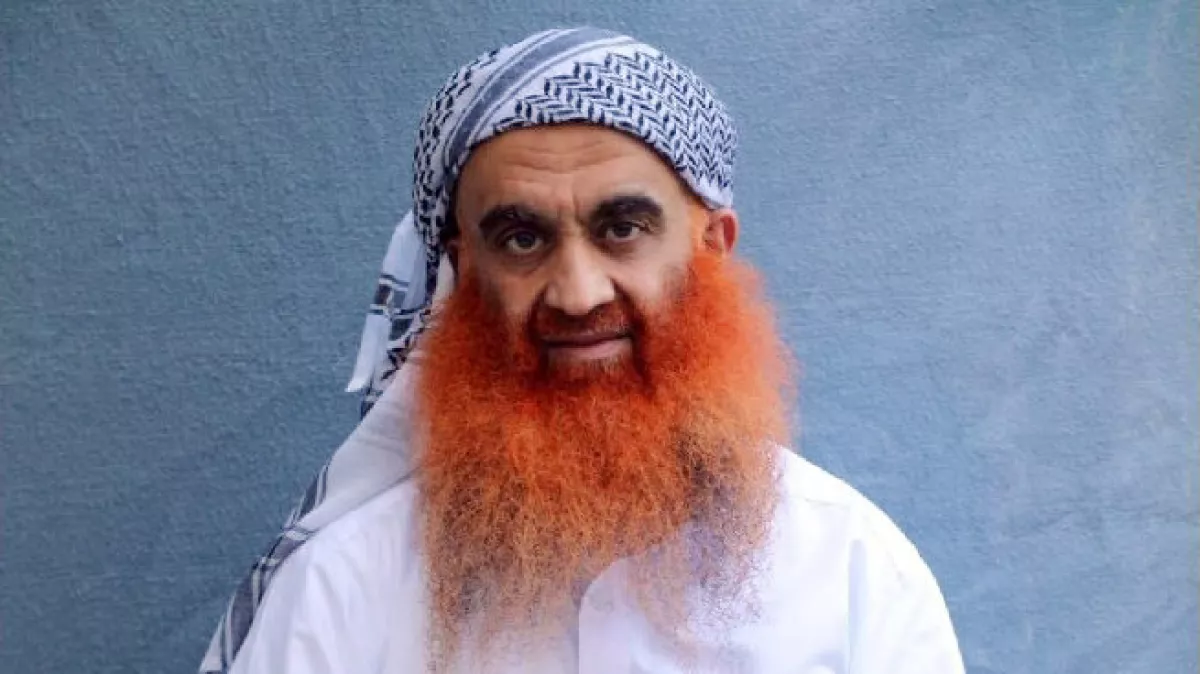

One of Washington’s most celebrated victories came in March 2003 with the capture of a dishevelled Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, seized from a hideout in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The 18-month global manhunt had netted al-Qaida’s No. 3 leader. Nevertheless, America’s attempt to bring him to trial continues to this day, with critics calling it one of the greatest failures of the “war on terror” approach that was adopted by the US government in the aftermath of the attacks.

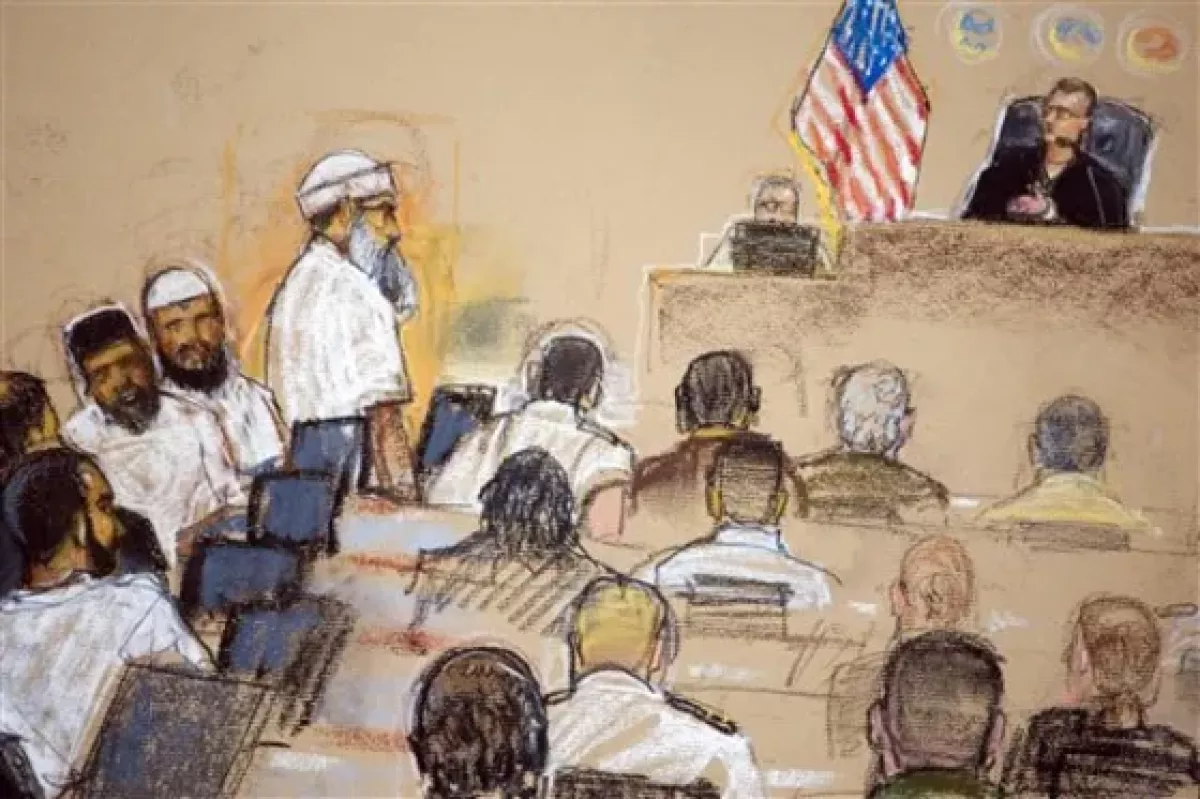

Mohammed and four co-defendants remain at Guantánamo prison, their tribunal repeatedly postponed. One of the latest developments occurred over this summer, stemming from a 2024 agreement by a senior Pentagon official allowing Mohammed and two others to plead guilty in exchange for avoiding the death penalty.

Then-Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III voided the deal, arguing it would cause “irreparable” harm to the government and public. However, the judge at the time in the case found that he was bound to the contract reached by the senior Pentagon official. Eventually, a federal appeals court this summer sided with Austin, ruling he “indisputably had legal authority to withdraw from the agreements.”

Supporters of the plea bargain, including some victims’ families and legal experts, had seen it as the only viable way forward. Instead, proceedings are again stalled, particularly after the presiding judge recently retired. His replacement must now review the massive case file and decide threshold questions, including whether confessions obtained under torture can be used.

Accusations of torture by CIA tainted trial

PBS notes the challenge traces back to what the US did after Mohammed’s capture. Held in secret prisons abroad, he and other suspects were subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques” tantamount to torture, rights groups say. Mohammed was waterboarded 183 times. A Senate investigation later concluded the interrogations produced no useful intelligence but triggered years of litigation over admissibility of FBI reports.

In the meantime, the US has killed other al-Qaida leaders, including Osama bin Laden in 2011 and his successor Ayman al-Zawahri in 2022. Yet Mohammed remains in custody. Investigators say a computer seized at his arrest contained photos of the 19 hijackers, letters from bin Laden, and operational details.

At a tribunal hearing, Mohammed admitted in writing that he swore allegiance to bin Laden, served on al-Qaida’s council, and acted as operational director for the Sept. 11 attacks “from A to Z.” He also claimed responsibility for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, a plot to down US planes with shoe bombs, the Bali nightclub bombing, and plans for follow-up strikes on the Sears Tower and Empire State Building. He further alleged involvement in attempts to assassinate President Bill Clinton and Pope John Paul II in the mid-1990s.

His long stalemate contrasts with the fate of his nephew, Ramzi Yousef, mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Captured in Pakistan in 1995, Yousef was tried in US civilian courts and is now serving life in prison. At trial, he defended his right to kill as comparable to America’s use of nuclear weapons. Mohammed has offered a similar argument at Guantánamo, saying through an interpreter that killing was the “language of any war.”

Where to go from here

If the case resumes, a new judge must revisit whether confessions made in CIA custody were unlawfully obtained. According to defense lawyers, Mohammed was waterboarded, rectally assaulted in a manner they described as rape, deprived of sleep, and subjected to other “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Under a recent ruling, War Secretary Pete Hegseth — who holds a new title after the department reverted to its historic name — now holds authority to “superintend the disposition of charges in these cases.” Visiting Guantánamo in February, Hegseth echoed Austin’s view: Mohammed “deserves the death penalty.” He added: “And I hope he finds it soon, through that system.”

Any trial would still be years away, beginning only after extensive pretrial hearings and appeals. It could last more than a year and require weeks or months to select a panel of military officers.

The advocacy group Sept. 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, which had backed the plea deals, lamented the appeals court decision. It said the ruling reminded “every victim family member that they may themselves die before seeing justice for their loved one. Already, far too many 9/11 family members have experienced that fate.”

By Nazrin Sadigova