The leitmotif of Munich 2026: Europe’s growing insecurity From Pax Americana to panic?

The sense of insecurity among European countries will be the leitmotif of discussions at the Munich Security Conference. And alongside such discussions, the very nature of transatlantic relations is changing.

Today, the next annual Munich Security Conference (MSC) kicks off in the Bavarian capital – the 62nd edition. The organisers emphasise the special significance and practical importance of the event given the current international situation. In principle, hardly any MSC in recent years hasn’t been introduced with similar statements, but this time they truly seem justified.

A crumbling elephant in a china shop?

Traditionally, the Munich week began even before the conference itself. On February 10, at a separate event in Berlin, MSC analysts presented the annual report. This time, it received an even more straightforward title than in previous years – “Under Destruction.”

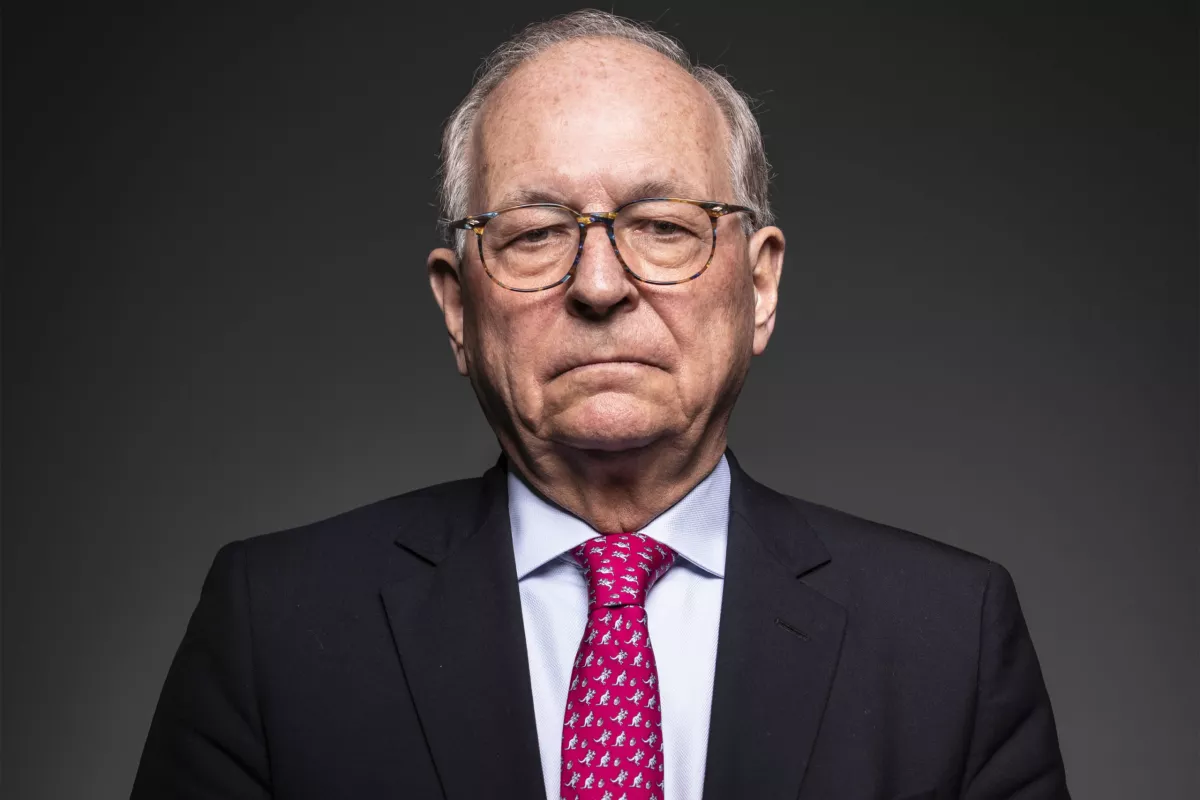

In his opening remarks on the report, Ambassador Wolfgang Ischinger, who has temporarily resumed his role as conference chairman, begins by noting the “profound uncertainty” in the world.

Of course, it’s hard to disagree with these words. The truth is, uncertainty didn’t emerge yesterday, so as a phenomenon we have already grown somewhat accustomed to it — at least to the extent that one can ever get used to uncertainty. Yet with each passing year, it truly increases in international relations, and there’s no end to this trend in sight.

At the same time, Ischinger emphasises a point that runs like a red thread throughout the report and will likely become central in the conference discussions. He identifies the United States and its policy under the administration of Donald Trump as the main factor behind global uncertainty. This argument can be read between the lines, and in some instances, it is stated outright.

According to Ischinger, the ongoing destruction of the world order is unlikely to create “the ground for policies that will increase the security, prosperity, and freedom of the people.” On the contrary, “ we might see a world shaped by transactional deals rather than principled cooperation, private rather than public interests, and regions shaped by regional hegemons rather than universal norms.”

With this reasoning, some might argue that the situation appears this way only through the lens of the European mainstream. Its representatives are accustomed to seeing the United States as the main constant of the liberal world order and, undoubtedly, to relying on Washington and the “security umbrella” it provides within their framework of international coordinates. However, many other countries and peoples have long ceased to view the now-collapsing order as fair, secure, or aligned with their key interests. For them, the United States—whose foreign policy prioritises transactional gains over abstract ideals—seems far more understandable and predictable. At least, for the time being.

Of course, this does not negate the thesis of soaring global uncertainty. Even if Washington’s foreign policy were to acquire some new, stable quality in the near future, the very fact that the system-shaping state of the old world order is entering a new phase brings with it immense uncertainty.

For example, this is also reflected in the recently released U.S. National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy under the Donald Trump administration. Although written in a straightforward and simple style, these documents leave no doubt that Washington itself still faces many unanswered questions before its strategy can take on clear and predictable contours.

In other words, the United States is still searching for its new place in an increasingly complex and less comprehensible world. This is natural, even if European allies view these developments with undisguised shock and alarm. In this context, the metaphor of a “crumbling elephant” used by the authors of the Munich Security Conference report is particularly telling. The elephant is clearly a reference to the United States. Calling Washington “the elephant in the china shop” would be both analytically incorrect and politically risky—but the image of a crumbling elephant carries significant symbolic weight.

Deep roots of the phenomenon

In preparing the report, the Munich Conference commissioned a series of public opinion surveys in several Western countries. The results indicate that the “process of disintegration” of the international system has deeper roots than the policies of individual states or their leaders. In most Western countries, there is clear evidence of profound public dissatisfaction with the political status quo—both internationally and within these countries themselves.

As the report’s authors emphasise, in all the G7 countries—the key Western states—only a small fraction of respondents believe that the policies of their current governments are capable of improving the prosperity of future generations.

Naturally, such sentiments are driving a large-scale crisis of trust in everything that has shaped the Western political mainstream for decades. Voters are increasingly looking toward alternatives—especially those offering radical solutions along the lines of “we are once again called to create a free world.” As a result, the political landscape is rapidly changing, almost in revolutionary fashion. It’s not yet a case of “those who were nothing will become everything,” but the direction of the trend is clear.

This observation is as important as it is obvious. Even more significant is that the Munich Security Conference has begun openly acknowledging it—although, in some ways, the spirit of the report still contrasts with its formal wording.

It seems that European elites are increasingly recognising the problem, yet so far they refuse to fully confront it. Despite the important acknowledgement of the deep roots of the “process of destruction,” and despite the correct formulation of the diagnosis, one can read between the lines a tendency among MSC analysts toward the wrong “treatment”—the desire to restore the Pax Americana and the corresponding global role of the United States. Yet this is impossible precisely because it is not Washington’s policy that set the world system in motion; rather, transformational processes within the system are predictably driving changes in American strategy and policy.

European security vs. transatlantic relations

As in 1963, when the very first conference was held in Munich (under a different name and format), the 2026 event still focuses on transatlantic relations—that is, essentially, relations within the larger NATO family. But the nature of the transatlantic discussion at the MSC will now differ significantly from past decades, as the published report clearly demonstrates.

In the past, allies on both sides of the Atlantic discussed common challenges as a consolidated front and worked out how to respond to them. Not that there were never contradictions, misunderstandings, or heated disputes within NATO—or even across the broader “collective West.” Over more than six decades, Munich has witnessed a great deal. Yet the essence and content of these discussions, the way questions were framed—even in difficult moments for the transatlantic allies—always differed from what can be read in the MSC 2026 report and agenda.

Previously, even differences in assessments or debates over tactical decisions did not pull transatlantic allies too far apart. They still saw a reason to approach contradictions and disagreements from shared positions, seeking solutions based on fundamental points of agreement. Even in passionate disputes, they primarily saw each other as allies.

Now, when looking toward Washington, Europeans—or at least most Europeans, though not all—see something different: risks, and even threats. And this automatically generates a sense of insecurity among the elites and societies of European countries. This feeling is growing sharply and, in some cases, verging on panic.

Thus, the tone of European questions and complaints about the long-standing “security umbrella,” as reflected in the Munich report, is easy to understand. The sense of European insecurity has become the leitmotif of this year’s Munich Security Conference. As the report’s authors emphasise, in Europe, the “US approach to European security is now perceived as volatile, oscillating between reassurance, conditionality, and coercion.”

Against this backdrop, MSC analysts understandably note that European countries still seek to maintain the U.S. military and political presence in Europe, while simultaneously preparing for greater autonomy. How viable scenarios of increased European autonomy are today is another question. Yet it is clear that alongside such discussions, the very nature of transatlantic relations is changing. As we observed following last year’s MSC, the emergence of a new “collective West” continues.

Perhaps, by the conclusion of Munich 2026, the contours of this new West will become clearer.