Azerbaijan and China forge strategic axis, redrawing Eurasia’s geopolitical map Photo

The Chinese outlet Asia Times featured an article by Canadian analyst Robert M. Cutler focusing on Azerbaijani-Chinese relations. Caliber.Az reprints this material.

"Western powers have, by and large, failed constructively to engage Azerbaijan following its restoration of integral territorial sovereignty. Filling the gap, China has been deepening its influence in the country while extending its reach into Georgia and even Armenia.

Beijing has been ramping up investments in the region’s digital infrastructure and financing energy projects. At the same time, powers such as Türkiye, Kazakhstan and the Gulf states have been raising their stakes in this strategic crossroads region.

Western actors have only recently begun to try to address the results of their failure to adjust their regional approaches after the 2020 Second Karabakh War.

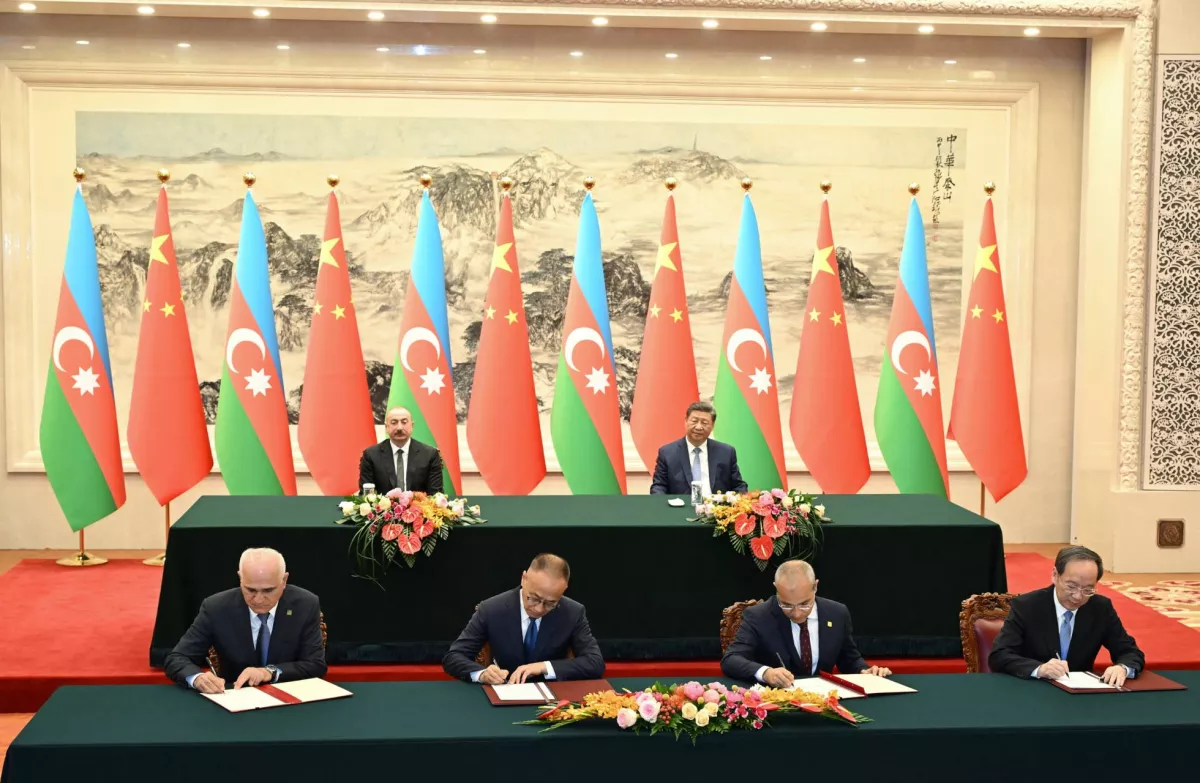

In this context, Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev’s April 2025 visit to Beijing marked a turning point in China’s engagement with the South Caucasus. This has now culminated in the signing of a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP), which represents the highest level of bilateral cooperation in the Chinese diplomatic hierarchy.

This upgrade builds on momentum since 2022, when the two sides formalized a strategic partnership at a Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit. Already, in 2024, bilateral trade reached US$3.74 billion, an increase of 20.7% over 2023, making China Azerbaijan’s fourth-largest trading partner.

Now elevated to comprehensive status, the relationship reflects alignment between China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Azerbaijan’s development strategies, including the “Silk Road Revival” and 2030 Socio-Economic Development plans. Beijing no longer treats the South Caucasus as a passive corridor but considers it an active node in trans-Caspian and trans-Eurasian integration.

The joint statement issued by Aliyev and China’s President Xi Jinping outlines broad cooperation in renewable energy, digitalization, intellectual property and aerospace, while giving primacy to transport and logistics.

Agreements also target joint projects in petrochemicals, metallurgy, automobiles and machinery. China will thus enter key Azerbaijani industrial sectors, complementing Baku’s push to diversify its economy beyond hydrocarbon fuels.

The West’s delayed response

The vacuum in Western strategy following the 2020 Second Karabakh War enabled China’s rising presence in the South Caucasus. After Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenia and the Russia-brokered ceasefire, the traditional Western-led peace process (the OSCE Minsk Group) was effectively sidelined.

Although Washington and Brussels sought separately to mediate talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and had some constructive successes in this, they failed to formulate a bold regional vision at a time when the geopolitical landscape was shifting.

Western engagement in the South Caucasus began to shift only in 2022, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine redrew the strategic map. The European Union launched mediation summits in Brussels and deployed a border monitoring mission to Armenia in 2023, which, rather than de-escalating tensions, has occasionally had the opposite effect.

The United States, meanwhile, stepped up its attention by 2023–2024: Secretary of State Antony Blinken convened trilateral meetings, and a special envoy for the region was appointed. Yet these efforts often lagged behind regional developments.

Facing no such constraints, China pressed ahead with a disciplined economic agenda that expanded its footprint through logistics, digital infrastructure and energy financing.

As Yerevan’s disenchantment with Moscow deepened, the United States and France began adjusting their posture, more definitely tilting toward Armenia. Political backing increased, and discussions of security assistance gained momentum. France became the largest arms supplier to Armenia as Russian sales nearly collapsed.

The Biden administration declined to renew the waiver for Section 907 of the US Freedom Support Act, a provision barring direct aid to Azerbaijan. It was the first time in over two decades that any American administration had done this.

Just days before the end of the Trump presidency, Biden’s Secretary of State Antony Blinken signed a US-Armenian strategic partnership charter with Yerevan’s Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan.

By 2025, the EU, too, had begun reassessing the region’s significance – not merely as a conflict zone but as a vector of energy and trade. A July 2022 memorandum with Azerbaijan aimed to double gas exports to Europe by 2027, although funding for the necessary expansion of the South Caucasus Pipeline is still uncertain.

The EU’s Global Gateway initiative now openly prioritizes Middle Corridor development, coordinating investment across Central Asia. In April 2024, an EU-Central Asia summit in Samarkand announced the launch of a Transport Corridor Alliance to support trans-Caspian routes.

These programs remain embryonic but signal a late recognition of the South Caucasus as part of a broader Eurasian connectivity matrix. Still, the Western response remains fundamentally reactive.

The region no longer depends on Euro-Atlantic frameworks alone. With China offering comprehensive partnerships anchored in infrastructure, trade and long-horizon investment, the South Caucasus now has real alternatives – and the means to exercise agency among them.

Logistics and connectivity: the Middle Corridor in focus

China was historically cautious in the South Caucasus, viewing it as Russia’s sphere of influence and favoring routes through Russia or Iran for its Europe-bound trade. The South Caucasus did not even figure in the original Belt and Road corridors.

The twin shocks of the 2020 Second Karabakh War and especially the 2022 Russian war against Ukraine disrupted Russian transit routes and changed all that. Beijing now sees Azerbaijan and its neighbours as crucial links in an alternative East-West artery connecting China to Europe

Aliyev has publicly noted that Azerbaijan is the second-largest investor in Belt and Road projects after China itself. Baku has spent enormously to upgrade ports, railways and highways to attract Belt and Road traffic.

Xi’s endorsement of Azerbaijan as a key transit node linking China, Central Asia and Europe affirms China’s intent to elevate the Middle Corridor from a secondary fallback path to a principal conduit.

The Middle Corridor’s potential was hampered in the past by sparse infrastructure and competition from faster Russian rail lines. Before 2022, only 2-3% of China-EU overland freight used the Middle Corridor.

The sanctions and instability arising from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, however, changed this calculus. In 2023–24, Kazakhstan saw a 63% increase in freight via this route (to 4.1 million tons), and Azerbaijan handled 18.5 million tons of cargo, a rise of 5.7%.

In late 2023, the rail companies of Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Georgia formed a joint venture to integrate customs and digital tracking systems, with a view to cutting freight times between China and Europe.

Azerbaijan, for its part, expanded the capacity of the new Port of Alat on the Caspian and modernized the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway. Azerbaijan and China agreed to streamline customs and finalize new road transport accords to advance direct trans-Caspian routes linking China and Europe via Azerbaijan.

Shippers in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan project that Middle Corridor container volume will reach 96,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs, a standard measure equivalent to about 33 cubic meters). This is a dramatic increase, although the volume is modest compared with Northern Corridor levels, still transiting Russia.

Digital and energy footprints: China’s techno-economic statecraft

China’s expanding influence in the South Caucasus is not limited to trains and ports. Digital infrastructure and energy financing are emerging as key tools of Beijing’s statecraft in the region, as they have already done in Central Asia, especially in Azerbaijan and Georgia. These sectors deepen China’s footprint while catering to local development needs.

In Azerbaijan, the new partnership prioritizes the digital economy and technology cooperation. Chinese telecom giants Huawei and ZTE have supplied equipment for telecom networks in all three republics over the past decade. Now, Baku and Beijing have agreed to promote the “digital transformation of industry” and set up joint tech R&D platforms.

Chinese soft power accompanies these tech investments. Confucius Institutes operate in Baku and Tbilisi, and a new Chinese language school recently opened in Yerevan with Beijing’s support. Such projects, while not massive, cultivate goodwill and familiarity with Chinese technology and standards.

In Georgia, a visa-free regime with China took effect in 2024, boosting tourism and business travel. Such a regime is also now in force between China and Azerbaijan. In this connection, Beijing has subtly been shaping the information environment, presenting itself as a new development partner for the Caucasus.

Chinese companies have stepped in alongside Middle Eastern investors to finance solar and wind projects. The 100-megawatt (MW) Gobustan solar plant, now backed by China’s Universal Energy, is only one example.

China now touts a “Global Clean Energy Partnership” that aligns with Baku’s intentions to develop its sunny plains and windy Caspian coast for large renewables projects, targeting both domestic electricity consumption and future exports to European markets.

In Georgia, Chinese firms have bid on hydropower plant tenders and acquired shares in the Poti Free Industrial Zone, which could include oil storage facilities. In Armenia, Chinese miners and investors are active in the copper and metals sector.

Armenia exports copper concentrate to China, and China has donated energy equipment like solar panels and transformers as aid. These moves ensure China has a stake in the Caucasus energy landscape.

Both Türkiye and China want stable, open corridors. Kazakhstan and other Central Asian states are likewise stepping up their involvement. Kazakhstan, in particular, is investing heavily to make the trans-Caspian link viable by financing port upgrades and purchasing new ferries.

The Gulf Arab states have emerged as another set of players. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia also see the region as an extension of their own bid to be Eurasian hubs.

The UAE’s logistics giant DP World has advised on the Alat Free Economic Zone in Azerbaijan, and UAE firms are reportedly eyeing stakes in South Caucasus infrastructure. Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power and the UAE’s Masdar have signed major deals to develop gigawatt-scale wind and solar farms in Azerbaijan’s liberated territories.

The South Caucasus gains agency

The cumulative effect of these trends is that the South Caucasus is acquiring autonomous agency. Azerbaijan, in particular, has leveraged its geographic position to elevate its strategic importance.

Georgia, long a supporter of alternative corridors, signed a free trade agreement with China in 2017 and then, in 2023, surprised many by elevating relations with Beijing to a strategic partnership. This came during Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili’s visit to China, after Georgia had felt somewhat distanced from the West and was looking for new investors.

Beijing’s interest is especially keen in the long-planned Anaklia deep-sea port on Georgia’s Black Sea coast. A Chinese state firm, China Harbor Engineering Company, has been contracted to develop the port, increasing Georgia’s dependence on Chinese capital.

China’s economic footprint in Armenia remains modest, without major investments. Aid is mostly symbolic, like school buses and a new TV tower studio.

The emerging geopolitical and geoeconomic network has made Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia more transactional in engaging all outside powers.

President Aliyev’s visit to Beijing in 2025 and the signing of the Azerbaijan–China comprehensive strategic partnership crystallize how Beijing’s deepening footprint is reorienting the region’s geopolitical compass.

The involvement of Türkiye, Kazakhstan, and the Gulf states reinforces this trend. Their investments and ambitions further anchor the Caucasus as a hub of trans-Caspian and trans-regional networks.

The West’s lagging response, particularly by the US and EU, has so far left the field open for China to play a more dynamic role. If Western nations wish to remain relevant in the South Caucasus, they will need to move beyond outdated frameworks and offer tangible connectivity and investment initiatives of their own.

The lesson of the past five years is that the South Caucasus will not remain a geopolitical backwater or mere bridge by default. It is actively, in complex-systems terms autopoietically—shaping itself into a central node of Eurasian connectivity. Aliyev’s Beijing trip is a clear signpost of that new reality.

Editor's note: Robert M. Cutler is a Senior Research Fellow, Institute of European, Russian & Eurasian Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa.