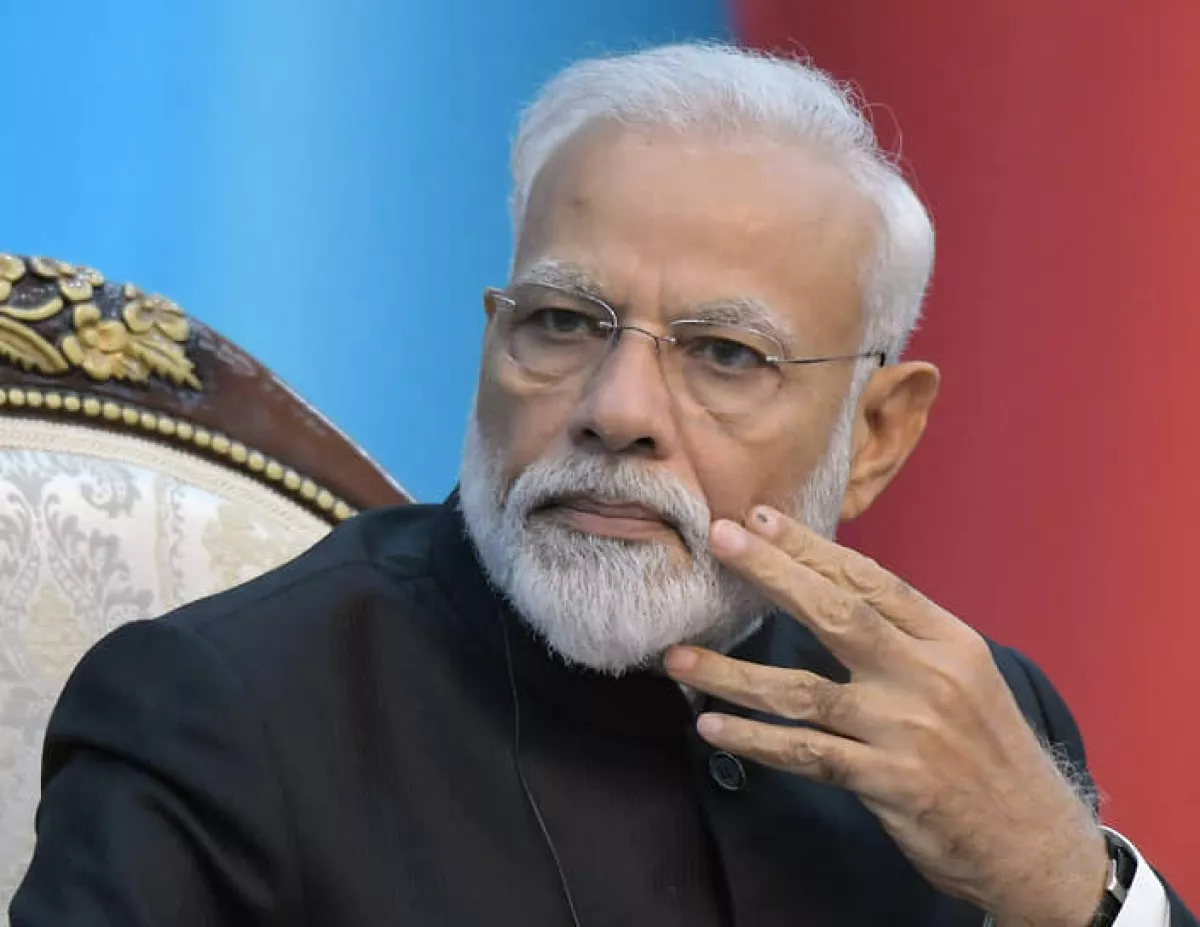

Modi’s chauvinism: from Gujarat to Dhaka India as a factor of instability

The nationalist policies of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi—particularly toward Muslims and, more broadly, the Islamic world—remain one of the central pillars of New Delhi’s state strategy.

In recent years, this syndrome of the Indian premier has become especially evident not only in the South Caucasus, far from India, but also in neighbouring Bangladesh. Evidence of this can be found in an article by prominent Indian National Congress politician and former minister Mani Shankar Aiyar, published in Frontline.

In the piece titled “Modi’s interventionist diplomacy squanders Bangladesh’s liberation-era goodwill,” the author speaks of the radically disruptive activities of Modi’s government, which presents itself as a “big brother” but has, in reality, turned the once well-disposed population of Bangladesh into a boiling cauldron of anti-Indian sentiment.

Background: Bangladesh is a South Asian state located in the north-eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. Most of its territory lies in the delta of the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers. The country borders India to the west, north and east, Myanmar to the south-east, and is washed by the Bay of Bengal to the south. The capital is Dhaka. Until 1947, the territory of Bangladesh was part of British India under colonial rule. Between 1905 and 1911, several attempts were made to partition the Bengal region into two provinces, with Dhaka designated as the capital of the eastern zone.

Relations between India and Bangladesh have deteriorated due to border disputes, the deportation of Muslims from India, and the Modi government’s interference in Bangladesh’s domestic politics. As a result, Dhaka accuses New Delhi of attempting to influence its internal political landscape, while the Indian side insists on protecting its interests and minorities in Bangladesh. However, according to international analysts, the growing mistrust between the two countries is largely driven by Indian nationalism, fuelled by the Modi government’s anti-Muslim policies.

In this context, it is particularly noteworthy that Mani Shankar Aiyar also draws special attention to this very factor, emphasising that the Indian prime minister and his inner circle have turned Bangladesh into an adversary on a par with Pakistan.

“The accent now is on Bangladeshi Hindus while firmly looking the other way at heartless Hindutva atrocities on hapless Indian Muslims (and Christians),” the author writes, arguing that India’s current policy is to portray Bangladesh as an oppressor of its Hindu minority in order to reinforce the narrative of incompatibility between Hindus and Muslims.

Notably, Hindutva (“Hinduness”) is the leading ideology of Hindu nationalism, aimed at establishing the cultural and political hegemony of Hinduism in India. Formulated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in 1923, it views Hinduism not merely as a religion, but as the foundation of the Indian nation, culture, and identity.

The publication also highlights another important nuance: “By treating a sovereign state as a vassal, by becoming an interventionist Big Brother playing domestic politics in a foreign country, which has caused bewilderment mixed with anger at the manner in which Modi’s India so egregiously backed Sheikh Hasina and alienated the vast majority of Bangladeshis upset at the oppression and unfettered corruption unleashed by her regime.” Yet non-interference in the internal affairs of other states was one of the core principles of Panchsheel—a principle that Modi has abandoned in favour of a transactional foreign policy.

In conclusion, the author stresses that the damage inflicted by the Modi regime is immense, but the situation could still be remedied if India were to eliminate communalism and chauvinism from both its domestic and foreign policy. However, it must regrettably be acknowledged that the sober reflections of the former minister are unlikely to materialise under the current Indian prime minister, who remains firmly entrenched in power—thanks in part to his cultivated image as a “man of the people.”

As is well known, Modi was born into the family of a small trader and from an early age helped his father in the shop—an experience that later became part of his political image. According to open sources, a key stage in the future prime minister’s formation was his underground activity during the Emergency of 1975–1977. At that time, disguising himself as a monk or a Sikh, he was reportedly involved in distributing campaign pamphlets and setting up a network of safe houses.

At the same time, critics argue that hostility toward Muslims runs like a red thread through the prime minister’s biography. In 2002, he was the head of the government in the state of Gujarat during the mass killings of Muslim men, women and children. After assuming the post of prime minister, he has been accused of persistently fuelling tensions along religious, linguistic and other lines, while Hindu extremists have allegedly committed acts of violence, intimidation and discrimination, including against Muslims, with impunity. Against this backdrop, international analysts warned in 2024 that Modi’s re-election to a third term could lead to an escalation of violence against Indian Muslims.

The outcome of this policy, critics say, has been that many Muslims were forced to leave their homes and now live in segregated neighbourhoods on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, the largest city and commercial capital of Gujarat. In May 2025, Raqib Hameed Naik, founder and executive director of the US-based Centre for the Study of Organised Hate (CSOH), stated in an interview with Anadolu that since Modi came to power in 2014, the situation—especially for Muslims and Christian religious minorities—has significantly deteriorated: “What was bad has become worse; the rise in hate crimes and hate speech against minorities has reached an unprecedented level in India’s history.”

Raqib Hameed Naik stated that Muslims have been lynched on suspicion of consuming beef or transporting cattle, and that such hate crimes against Muslims have reached their peak. He also drew attention to the demolition of Muslim-owned properties, attacks on places of worship, and discriminatory legislation. According to him, millions of Indian Muslims risk being rendered stateless due to the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

“In many Indian states governed by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), laws have been adopted based on unfounded theories such as ‘love jihad,’ ‘land jihad,’ and ‘spit jihad.’ In effect, they are aimed at criminalising the expression of Muslim identity or anything perceived as belonging to Muslims,” Naik said.

In this context, it is also worth noting that in September last year, the website Clarion India published an article examining how Modi’s policies are affecting the lives of Indian Muslims. It stated that in Assam, harsh measures against the Muslim community continue, with the state government reportedly employing aggressive tactics such as deportations, bulldozer demolitions of homes, and the targeting of entire families under the pretext of illegal infiltration.

“It is shocking to see entire families, including women and children, being pushed out without proper investigation or hearing,” said Ayesha Rahman, a resident of Karimganj. “This is not just a violation of rights but a clear act of targeting our community.”

Modi’s alleged religious intolerance was also addressed in an article published in August 2024 in the Pakistan Observer. Its author, Professor of Political Science at the International Islamic University in Islamabad, Muhammad Khan, stressed that today the Muslim community does not feel safe in India: if you are a Muslim, you can be attacked anywhere and at any time.

“[...] Muslims in India are facing all sorts of discrimination, alienation and humiliation besides being killed and converted into Hinduism, other minorities are equally being endangered and oppressed,” the professor noted.

According to The Catholic World Report, in 2023, thousands of Christians and Muslims were attacked and intimidated, and hundreds of churches and mosques were destroyed. At the same time, an analysis by the Pew Research Center ranks India fourth out of 198 countries in terms of religious intolerance.

Thus, taken together, all of the above-mentioned facts suggest that despite its status as one of South Asia’s leading powers, India under Modi is portrayed by critics as a country where such universal civilisational values as tolerance and multiculturalism have been significantly eroded.

In this light, it can be argued that the policy of intolerance so vigorously pursued by the Indian prime minister deals a serious blow to the republic’s image on the international stage and, if continued, could steer the country towards becoming a mono-confessional and mono-ethnic state. History has repeatedly shown the consequences of implementing theories based on the supposed superiority of one group over others—and humanity has encountered them more than once.