Rolling Stone: The European mass graves you never knew about The remains of 4,000 Azerbaijanis still missing from the First Karabakh War

Taras Kuzio, a research fellow at the Henry Jackson Society has published an article for the Rolling Stone magazine. Caliber.Az reprints the article.

Thirty years before Bucha, before the massacre in Srebrenica, mass graves were dug and filled with thousands of civilian victims in a conflict on the borders of Europe. With their remains only being unearthed and catalogued today, Taras Kuzio asks what happened and discusses why these crimes must be revisited.

In early April 2022, Adalat Verdiyev was the first of a group of military engineers to make a grim discovery.

While digging the foundations for a temporary building in Farrukh Heights, a tiny hilltop town in Karabakh, Azerbaijan, in the South Caucasus, they uncovered 20 bodies. They had rested there for 30 years, while above them, life for those who had moved into the dead people's homes had simply gone on uninterrupted.

Other bodies have been revealed in the ghost towns of Karabakh. In Edilli, Aghdam, Fuzuli, Khojavand and Shusha, close to 200 corpses have been found in exploratory digs in the first three months of this year alone. Some finds were unexpected, but elsewhere those searching knew precisely what they would unearth: the remains of some of the 4,000 Azerbaijanis still missing from the war over the southwest territory of Nagorno-Karabakh fought between Armenia and Azerbaijan a generation ago.

Europe and the world stand aghast at the horrors of Bucha in Ukraine, where decomposing bodies were found discarded in the streets. But in Karabakh, the site of a mostly forgotten conflict on Europe's distant borders, the same had been seen 30 years before. What places Farrukh Heights and Bucha apart is not the design, nor the attention. It is simply the passage of time: not weeks, as in Bucha, but a generation in Karabakh before friends and relatives have been able to recover the bodies and pay respects to their dead.

What happened in the early 90s and why is little known beyond the Caucasus. For the world to understand, these atrocities must now be revisited.

The early 90s Nagorno-Karabakh war between Azerbaijan and Armenia - who laid claim to the Karabakh region due to its majority Armenian population - escaped scrutiny. The Cold War, most westerners believed, was won. Whatever might have been happening in the Caucasus was Moscow's problem; any suggestion that the West might involve itself in Russia's immediate backyard would only fuel the idea that the Soviet Union's fall had been anything but an unadulterated success. No one wanted to muddy that narrative.

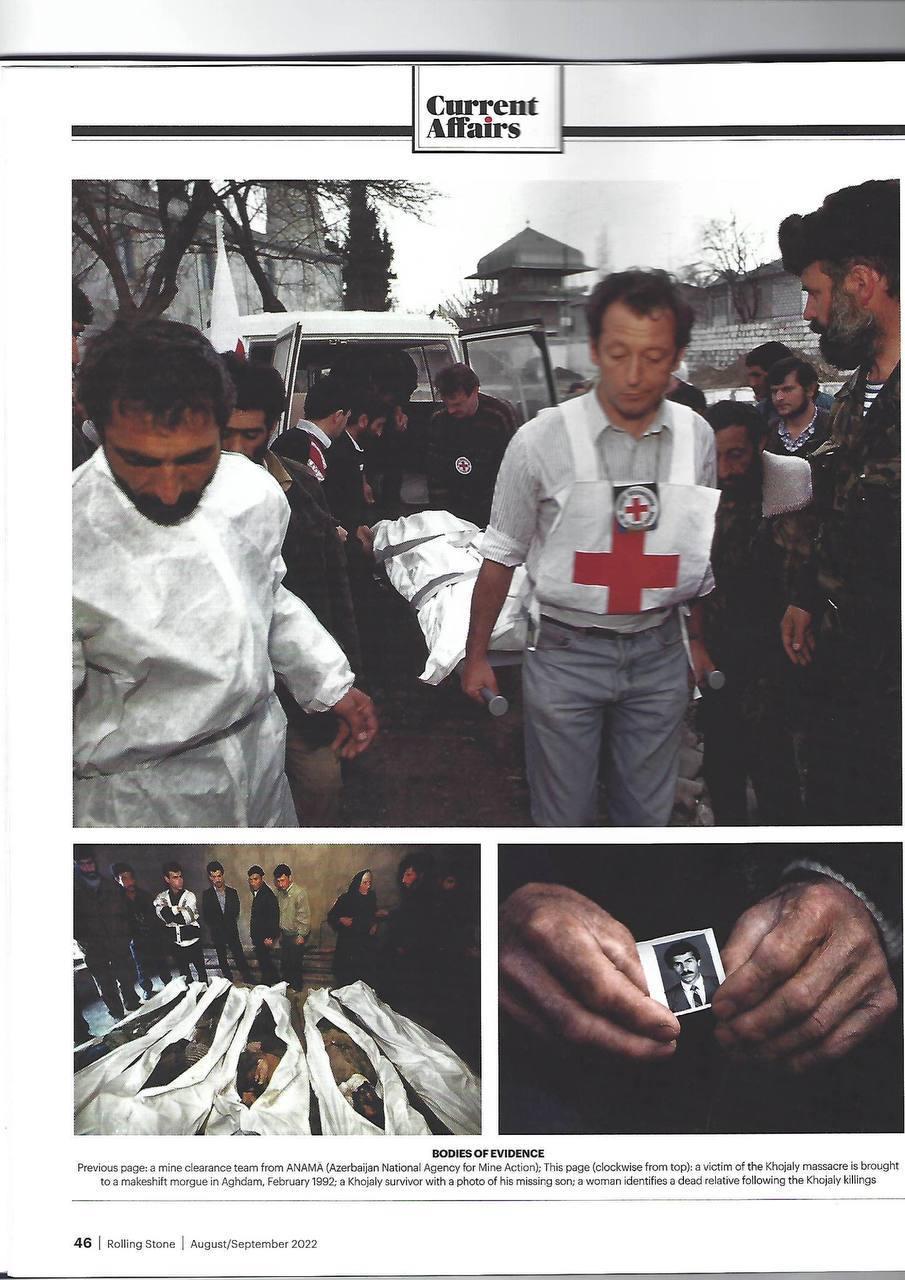

What news coverage there was of the massacre at Khojaly, where 613 Azerbaijani civilians were killed by Armenian forces on one day in February 1992, was soon forgotten. It was one of many incidents in a war that lasted half a decade.

Two years later, the Tutsi genocide in Rwanda and then Srebrenica in Bosnia in 1995 shocked the world. The preceding war in the Caucasus should by rights have registered as a wake-up call for what was to come. In the first two years of the 90s, 30,000 - mostly civilian - Azerbaijanis were murdered when Armenia gained the upper hand with support from Moscow.

The prize was Karabakh (known to Armenians as "Artsakh"), a region where Azerbaijanis and Armenians had lived side by side for generations. For hundreds of years, its hilltops were home to Armenian churches, Shia and Sunni Azeri mosques, and even the occasional Russian Orthodox onion dome. Agricultural labour was tough in winter, life was far from perfect, and long-held prejudices were too often left unaddressed. Yet widespread intermarriage, movement between faiths and families was evidence that, though complex, this was a stable community.

But by the war's end in 1994, a fifth of Azerbaijan was under Armenian control. Around 860,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis fled, but 4,000 were left behind: the murdered and missing. Only now are their remains being uncovered and accounted for.

Few make the connection between the horrors of the Soviet disintegration and events in Karabakh, Rwanda and Bosnia. The collapse or departure - and then silence -of their Cold War sponsor was not the cause, but it was a trigger: the lid torn off from deadening authoritarian control that had repressed but never suppressed ethnic divisions. Facing economic crises and societal flux, venal politicians would revive them in all three.

In the decade prior to the Soviet Union's collapse, sharp economic decline gave way to reactionary and racist political forces. Convincing embittered and impoverished populations of their victimhood at the hands of a demonic ethnic "other", politicians such as Robert Kocharian, first president of Artsakh - a state which is not internationally recognised - and later president of Armenia, proclaimed "Armenians and Azerbaijanis are ethnically, genetically incompatible." So powerful was this racist message that a succession of political and military leaders from Artsakh transitioned to lead Armenia itself. Kocharian was succeeded as president of Armenia by Serzh Sargsyan.

Riding the same wave as his predecessor, Sargsyan had been defence minister of Armenia during the 90s Armenian-Azerbaijan war when Kocharian was the leader of Artsakh. "Before Khojaly, the Azerbaijanis thought that they were joking with us, they thought the Armenians were people who could not raise their hand against the civilian population. We needed to put a stop to all that," said Sargsyan, without remorse, eight years after the massacre which saw children butchered and others burned or decapitated.

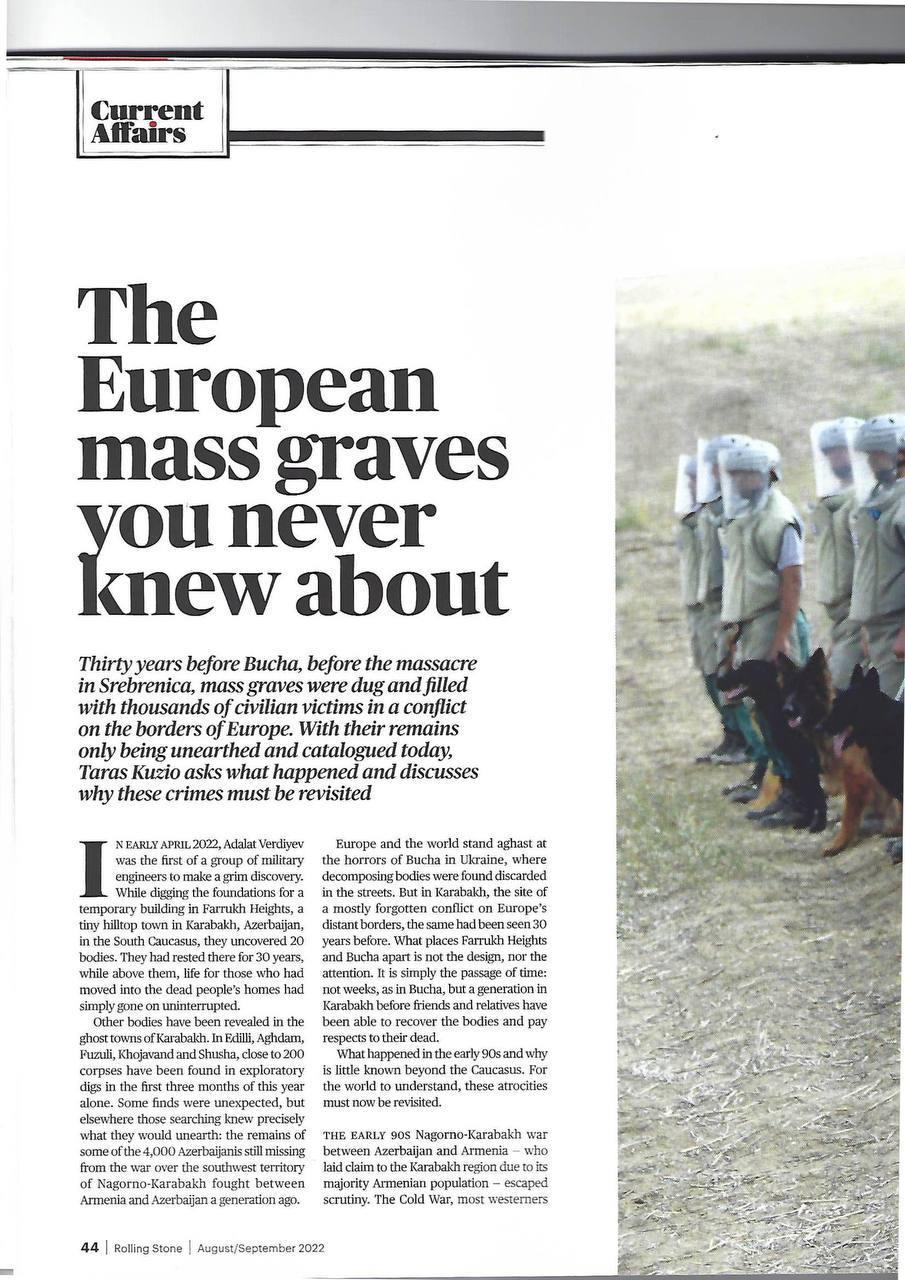

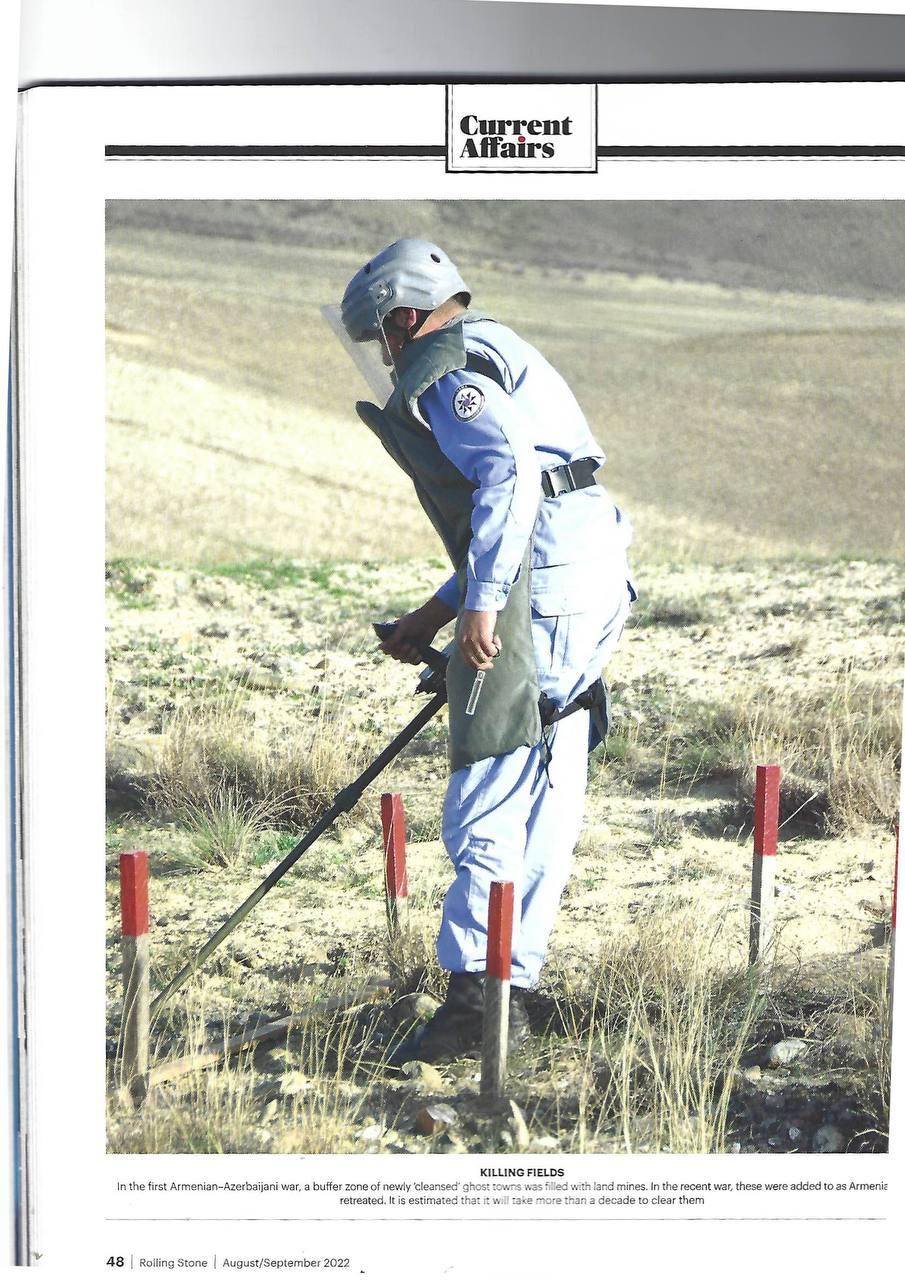

But Khojaly was only the first. Shusha, an exquisite medieval town, witnessed the battle that started to turn the war. A mass grave housing the hundreds executed by the victors was only unearthed in 2021. Next, Aghdam, an industrial town of some 30,000, was cleansed, tiles stripped from roofs, family heirlooms taken and sold, every building demolished - except for the mosque left standing to be desecrated as a pigsty. From an original plan to "liberate" Stepanakert, Artsakh's capital, and its surrounds from Azerbaijani control, a more expansive and organised effort evolved: to rid the whole of Karabakh of ethnic Azerbaijanis and then seal it off from the rest of Azerbaijan with a buffer zone of newly cleansed and demolished ghost towns. That zone was filled with land mines. In the recent war, these were added to as Armenian forces retreated. It is estimated it will take more than a decade to clear them.

To date, both Kocharian and Sargsyan remain unrepentant. On the contrary: their activities during the war have been the making of their domestic political careers. Rather, the burden of justification has fallen to the Armenian diaspora, which forms a sizeable and effective lobbying force -particularly in France and the US.

This year, as support for Ukraine, became the focus of appropriations by US Congressional budgeteers, this chasm of disconnect was writ large: Rep. Adam Schiff, vice-chairman of the Congressional Armenian Caucus, called on House and Senate Appropriations to fund Artsakh to the tune of $50 million. The justification for being handed US taxpayers' cash was that these were "democrats and allies" whose lands, culture and very existence were under threat from a revanchist Azerbaijan.

But the idea that Artsakh or even Armenia are friends of the West is just as baseless a fiction as that which claimed Azerbaijanis and Armenians could never live together. Only days into the Ukraine war, the president of Artsakh called for the liberation of Donetsk and Luhansk - sovereign regions of Ukraine by Russia's invading forces. Kocharian has been on the board of AFK Sistema, the Russian corporate giant, since 2009; only a month before Russia's Ukraine invasion he called for Armenia's "full-fledged integration" with Russia through the subsuming of A1menia into the "Union State of Russia and Belarus", a political entity that has united those two nations since the end of the Soviet Union.

Other, more recent political leaders - often hyped as pro-Western -have proved no less pro-Russian under pressure. The current prime minister of Armenia, Nikol Pashinyan, elected by a westward-hopeful youth vote, currently chairs Russia's Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the six-nation military alliance of which Armenia is part. His economy minister has publicly encouraged Russian companies to move to Armenia - a member of Russia's five-country economic and customs pact - for sanctions avoidance. Pashinyan himself said, "We must discuss what operational decisions need to be made to ensure that these negative effects are minimal or, if possible, circumvent them through appropriate decisions."

However, western politicians - some dependent on the Armenian diaspora for votes, others on the right because of religious bias - choose to believe a compelling story of how Artsakh is the ancestral lands of the first Christian people of the Caucasus, and the cradle of modem Armenia. Moscow spins a similar tale of Kievan Rus - today's Ukraine - as the medieval national, cultural, and religious precursor to the Russian Federation.

Armenia no longer controls all of Karabakh. ln 2020, the two countries went to war again, with much of the occupation reversed. In the areas regained, the rumoured yet hitherto unverifiable mass graves are now being unearthed. Once exhumed, the contents are documented, then samples matched to those from relatives stored at a DNA bank.

This is the long, meticulous search for truth that can bring closure to the nation's darkest chapter. Without it, the wounds will not heal; the grip of the past unable to yield to a more reconciliatory future.

Instead, the forensics of science will replace the politics of memory, the destructive capacity of the latter on full display in Ukraine today. For Azerbaijanis, the material proof of the fate of family members offers the chance to move forward. In a region of stale antagonisms, a broader story might now emerge that can accommodate both Azerbaijanis and Armenians in Karabakh - just as in the past.

For Armenians, this could be more difficult. Having grown used to the status quo of occupation, and a political narrative that told them their conquest was just, Karabakh's Joss may sit uneasily. But there are also many in Armenia that see the retention of the region in breach of international law as a nationalist phantom, and a distraction from more pressing domestic concerns such as corruption, endemic unemployment and a stuttering economy. All three issues have been fed in part by the occupation: Armenia's resultant regional isolation has hampered economic development, while occupants of office ensure dwindling opportunities are dispersed to those that will pay in kind.

For those that see such truths know that the recent conflict need not lead to another tit-for-tat situation. A peace deal yet unsigned could secure the many rights of Armenians in Karabakh, without the need for occupation their former leaders proclaimed existentially necessary. The ghosts of the past, on both sides of the border, must now be laid to rest if a different future is to unfurl.