Georgians say they want to join Europe, but not like this

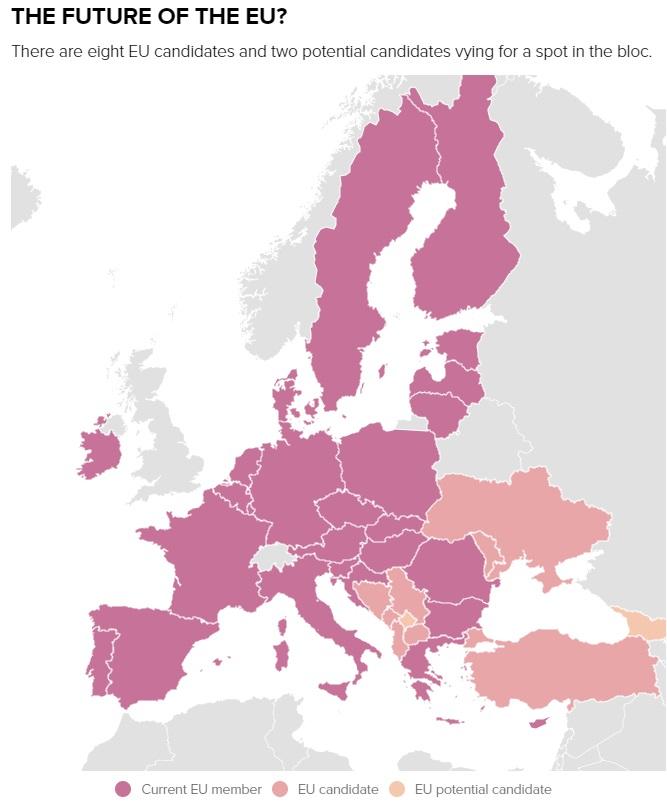

If all goes as expected, Georgia will take the first step on the long road of joining the European Union this week.

But even for those in the former Soviet country who have spent decades working for just this moment, now that it has come, it is at best bittersweet, according to POLITICO.

“The problem is not technical, it’s fundamental,” former Georgian president Mikhail Saakashvili wrote from prison in a note to POLITICO.

“Georgia is a state seized by one oligarch controlled from Moscow,” he added. He’s referring to Bidzina Ivanishvili, a former prime minister and billionaire businessman who made his money in Russia and is widely seen to be pulling the strings of the ruling Georgia Dream party he founded.

Although Saakashvili, who is serving a six-year prison sentence for “abuse of power,” may be a controversial figure, his view is widespread among the country’s pro-EU camp. The issue is timely as European leaders gathering in Brussels this week get ready to decide whether to act on a European Commission recommendation to extend formal candidate status to Georgia — the first official step on the long road to membership.

Ukraine and Moldova took that step in June 2022 following Moscow’s full-scale assault on Kyiv, leading many in Georgia to see their own progress less as a sign of merit and more of the EU’s sliding standards in the face of geopolitical jitters.

“As a student, I used to picture it as the sky opening and some kind of miracle happening,” said Vano Chkhikvadze, EU integration program manager at the Open Society Georgia Foundation, a nongovernmental organization.

“Never ever did I think it might happen like this — like getting a diploma without real knowledge.”

Counterrevolution

For decades, Saakashvili represented the pull of Europe and the tensions that can result from that in a country wedged between Turkey and Russia.

In 2003, as an opposition politician, Saakashvili boarded a bus in the western town of Tsalenjikha and led a protest convoy to the capital against corruption and rigged elections.

Several weeks later, in what would come to be known as the Rose Revolution, then-President Eduard Shevardnadze, a former Soviet minister, resigned.

Saakashvili’s election as president the next year heralded a golden age for Georgian-Western relations, as the country stepped out of Moscow’s shadow and sought EU and NATO integration.

But during his decade in power, Saakashvili became a symbol of political division.

His supporters praise him for overhauling the public sector, especially the police, and tackling crime and low-level corruption.

But his critics accuse him of authoritarian tendencies, losing one-fifth of Georgia’s territory to Russian military control in a brief 2008 war, and not going far enough with democratic reform, particularly of the judiciary.

Those who argue the latter point to the current state of the country as a case in point.

Though Ivanishvili says he is no longer active in politics, many in the country see him as using control of Georgian Dream to nudge the country back into Moscow’s orbit.

Meanwhile, Saakashvili is in prison, where his health rapidly deteriorated following a hunger strike.

The Rose Revolution laid the foundation for “a functioning, successful state, undermining the Russian narrative that the post-Soviet space was doomed to fail,” Saakashvili wrote in note to POLITICO.

Now, he added, “counterrevolutionary forces” are undoing his work, with Russia’s assistance.

U-turn

Georgian Dream came to power in 2012 on a pro-EU agenda — a political no-brainer considering Georgians’ overwhelming support for closer integration.

“Our place is there in Europe, in a place of freedom,” is how Gocha Shanava, a 62-year-old flour vendor, put it. “For us and for our children: It’s a matter of life and death.”

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine changed the government’s calculus, setting in motion two apparently contradictory processes.

Weeks after Russia’s invasion, Georgia’s government jumped on the bandwagon with Ukraine and Moldova, applying for EU membership. It then proceeded to seemingly do everything to prevent a positive outcome.

It did not join Western sanctions against Moscow (Russia’s share in Georgian trade reached a 16-year high this year) but instead restarted direct flights to Russia after Moscow lifted a flight ban.

It also dismissed EU concerns about Saakashvili, who Russian President Vladimir Putin once said deserved to be “hung by the testicles.”

Critics have also decried a proposed bill by Georgian Dream parliamentarians to label NGOs and media that receive funding from abroad as “foreign agents” — a law almost identical to Russian legislation the Kremlin has used to hound its critics.

If, as some in the country believe, these mixed signals were part of a maneuver to force the EU into giving Georgia a thumbs-down on its bid, it partly succeeded.

At the same meeting in June when Ukraine and Moldova received candidate status, Georgia’s was put on ice, pending 12 “priorities” for improvement, including “de-oligarchization” and reducing “polarization.”

Wannabe Orbán

While some in the opposition point to Ivanishvili’s business ties to Russia as the reason behind Georgia’s ambiguous stance, the government has argued it is resisting Western attempts to drag it into the war with Russia.

Many analysts describe the government’s motivation as simpler.

“You can’t say directly that it’s pro-Russian. It’s worse: It’s opportunistic,” said Kornely Kakachia, director of the Georgian Institute of Politics, a nonpartisan think tank. “In order to hold on to power, it’s ready to cooperate with anybody.”

That includes China, with which Georgia this summer agreed a “strategic partnership” following a visit by its prime minister to Beijing.

Kakachia believes that Georgian Dream is aiming for EU candidacy status, if only to claim credit for it ahead of parliamentary elections next year. But by courting the competition, it hopes to pressure the EU into offering a financial lifeline without all the moral finger-wagging.

“Georgia is trying to act like Viktor Orbán’s Hungary before even being part of the EU,” said Gela Vasadze, an independent political analyst based in Tbilisi.

Notably, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán — who is threatening to derail Ukraine’s accession prospects (the next step after candidacy) — staunchly supports Georgia’s bid.

Crossroads

The EU now faces a difficult choice.

Giving Georgia candidacy risks encouraging Georgian Dream on its anti-democratic path and undermining the EU’s own credibility.

But leaving the country dangling will demoralize Georgia’s population and likely push its government into the open arms of regional rivals.

In a timely reminder late November, the Russian Duma’s foreign affairs committee applauded Georgia for its “courage in not succumbing to anti-Russian hysteria,” noting the contribution Russian tourists made to the country’s economy.

The EU has responded with doublespeak of its own.

In a report this November, the European Commission gave Georgia a preliminary green light, despite noting significant progress in only three of 12 “priority” areas.

Commenting on the 122-page report — in which Ivanishvili does not appear once — European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen sounded a critical note, saying the European aspirations of the Georgian population “need to be better mirrored by the authorities.”

Yet at the same time, she commended those authorities for their “action plan for de-oligarchization” — a plan critics have described as vague and likely ineffective.

Safety concerns

Along with a recent interview in which Germany’s ambassador to the country praised its “excellent progress,” von der Leyen’s statement has caused head-scratching among some in Georgia’s pro-EU camp. They argue the EU shouldn’t expect real progress on issues like de-oligarchization under the current government.

“It’s like asking someone to cut the branch they’re sitting on,” said Chkhikvadze.

Chkhikvadze said safety concerns had prompted many within his circles to make contingency plans for a life outside Georgia.

His own work monitoring Georgia’s lack of progress on the EU’s action points earned him the ire of state television and prompted the chair of Georgian Dream’s Irakli Kobakhidze to call him a traitor.

Georgia’s pro-EU analysts say what is needed from the EU is a long-term vision on how to turn the country around politically and economically, and help break a long tradition of one-party rule.

Without such a vision, candidacy status is “like treating cancer with penicillin,” said Kakachia.