Azerbaijan’s stone sculpture: mastery, culture, and spiritual symbols A lookback at history with Caliber.Az / Part I

The territory of Azerbaijan has long been distinguished by a rich cultural layer, where traces of various epochs, civilisations, and artistic traditions intertwine. Each generation has left its mark here — in architecture, ornamentation, ritual symbols, and sculpture. One of the most striking expressions of this heritage is Azerbaijani stone sculpture — an invaluable phenomenon that reflects the customs, worldview, and dynamics of cultural change of the people.

Stone sculpture is a form of visual art, consisting of carved figures of humans, animals, or reliefs made from stone. It is one of the oldest forms of sculpture, requiring special skill and artistic vision, often connected to cultural, religious, or ritual traditions. In the context of archaeology and ethnography, it includes statues, tombstones, and other artefacts that reflect the worldview of the people. Foreign travellers visiting Azerbaijan were long fascinated by the abundance of reliefs depicting animals, humans, and entire narrative scenes carved on gravestones. Stone sculptures can be found in the steppes of Shirvan, Mughan, on the plains of Karabakh, in Gazakh, Nakhchivan, and other regions, many of which have survived to this day.

Most of these monuments remain where they were created centuries ago. Carved from Absheron sandstone, dark grey Karabakh boulders, or basalt, they tell not only of the skill of anonymous folk sculptors with their individual artistic styles but also of the worldview, aesthetic sense, and spiritual experience of an entire people.

These burials can be roughly divided by dating and region, yet their value lies not only in chronology. Each era left its unique imprint, turning Azerbaijan into a kind of historical chronicle. These are not merely burial sites but a multilayered historical and cultural stratum, where traces of different civilisations, religious traditions, and ways of life coexist. Such a rich heritage makes these monuments a key to understanding the historical and cultural development of the region and an invaluable resource for further research.

Across Azerbaijan, there are numerous kurgan (burial mound) sites scattered throughout various regions. These monuments belong to different periods and demonstrate the richness of funerary traditions. Artefacts found in kurgans allow researchers to delve deeper into the culture, customs, and rituals of the ancient peoples who inhabited these lands.

Some kurgans represent large and complex architectural-ritual complexes of global significance. Particularly notable are the Borsunlu kurgans in the Tartar district, kurgans in the Khojaly district, the extensive kurgan fields in the Keshikchidagh Reserve, monuments on the Mil plain, and many others.

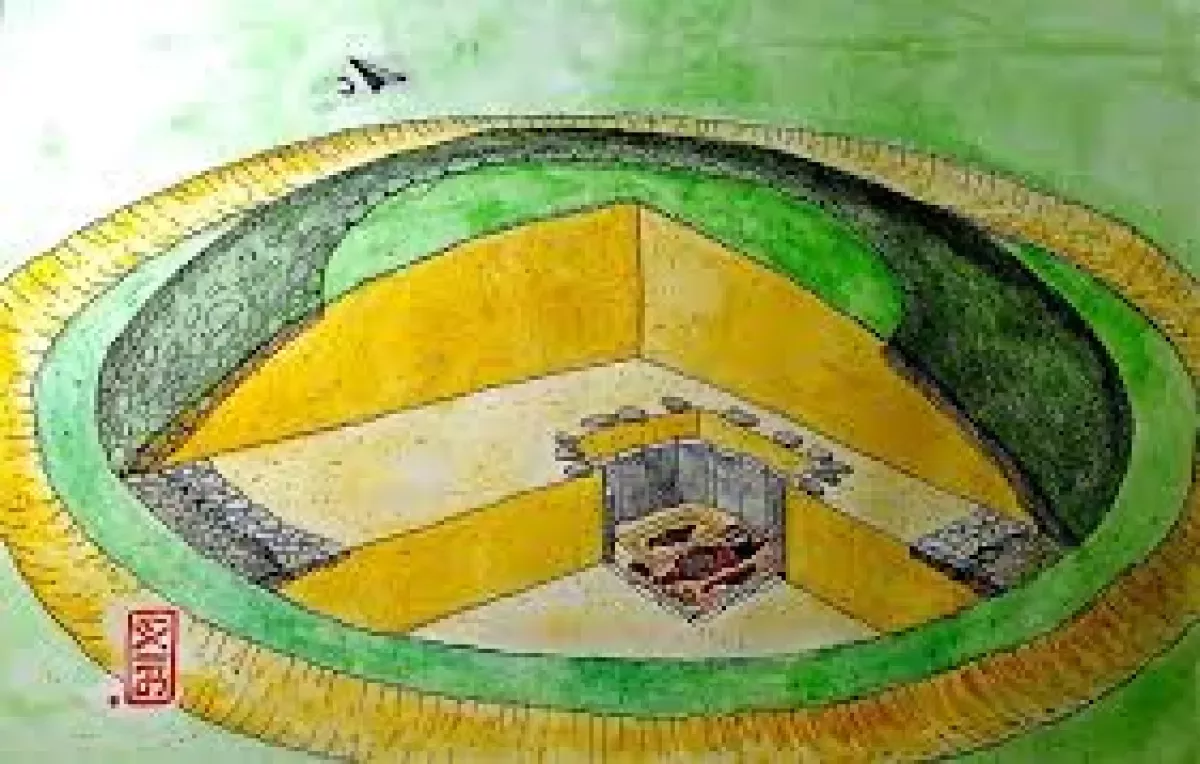

The uniqueness of kurgan burials reflected the worldview of our ancestors, their understanding of the universe, and their relationship with the afterlife. Despite differences in construction and decoration, nearly all kurgans adhere to common religious principles: the world was perceived as consisting of three levels — celestial, terrestrial, and subterranean. This model of the universe was characteristic of the cosmological views of many ancient cultures and naturally found expression in burial practices.

Preparation for building a kurgan began with clearing the land, symbolising the earthly circle. Its diameter depended on the social status of the deceased and could range from 3 to 150 meters. The perimeter of the circle was marked with a dense ring of worked or semi-worked stones — also depending on the status of the deceased.

The central chamber, referred to in Russian literature as a “domina,” represented a model of a human dwelling in the afterlife. Personal belongings and weapons of the deceased were placed in the kurgan burial, and in some cases, their horse or even a chariot, reflecting the belief in the continuation of earthly life in another world. For members of the upper classes, such burials were supplemented with jewellery, clothing, armour, and rich armament, emphasising the status of the deceased and their place in the social hierarchy.

The design of the chambers could vary greatly — from a simple pit lined with boulders or pebbles to complex constructions of stone, logs, or bricks. The depth of burial beneath the mound sometimes exceeded 10 metres. The completed kurgan, covered by an earthen mound, symbolised the celestial dome and acted as a model of the universe in which human life unfolded. It appears that within this model, the afterlife was also anticipated.

Kurgan burials in Azerbaijan demonstrate remarkable stability and longevity of traditions, the depth of spiritual beliefs, and the high organisation of the society of our ancestors. They remain a valuable source of knowledge about the culture, religion, and worldview of the ancient peoples of the region.

Among the oldest monuments of Azerbaijani stone sculpture are anthropomorphic statues. Figures of humans are of particular scholarly value. In the valleys of Karabakh and the steppes of Shirvan, stone statues up to three meters or more in height have survived to this day. These monuments are characterised by massiveness and monolithic form, with deliberate avoidance of excessive detailing.

On most statues, the hands are placed on the chest, and a braid is embossed on the back of the head. Most figures are depicted nude, though there are also statues showing humans clothed. Scholars believe that these stone figures embodied images of the deceased, primarily brave and noble warriors. Despite their schematic execution, they make a strong impression and are regarded as cult monuments revered by the peoples inhabiting present-day Azerbaijan.

Archaeologists associate these statues with a broad circle of similar monuments spread across vast territories of Eurasia — from southern Russia to southern Siberia and Central Asia. Such parallels allow Azerbaijani monuments to be considered in a broader cultural-historical context, reflecting common ideas about the world, ancestor cults, and artistic traditions of ancient nomadic and sedentary peoples.

These statues had a cultic significance and were closely linked to burial rituals. Researchers believe that, besides their ritual function, they also served an ideological purpose — symbolising the strength, resilience, and power of the people who erected them. It is no coincidence that such statues were placed on elevations or along ancient trade routes, where they served not only as monuments to the deceased but also as guardians of the land.

As noted by researcher Rasim Afandiyev, the appearance of such statues in Azerbaijan dates to the 3rd–7th centuries, though some scholars consider them even older. The ritual of installing stone statues is described in detail in the works of Georgian and Arab historians of the 7th–11th centuries. The Albanian chronicler Movses Kaghankatvatsi, in his work History of the Aghuans, emphasised that such statues were erected in honour of outstanding warriors and commanders. He also mentioned the burial ceremonies accompanying the installation of monuments: they were conducted solemnly — with songs, dances, and reenactments of battles, reminiscent of the deeds of the deceased hero.

Over time, these statues became objects of veneration and places of pilgrimage. They were treated with special respect, safeguarded as sacred relics. The chronicles of Movses Kaghankatvatsi note that any desecration of such statues was regarded as sacrilege and could provoke the “wrath of the god Tangrykhan,” reflecting the deep faith and high sacred status surrounding them.

There was also a “new” stage in the development of Azerbaijani stone sculpture, associated with the feudal era. During this period, the art of stone carving acquired new forms and expressive means, achieving a high level of artistic mastery.

A special place among monuments of that time is occupied by the so-called Bailov Stones — relief slabs raised from the bottom of the Caspian Sea. They are dated to 1232–1233 and are inextricably linked with the sunken Bayil Castle in Baku, of which they were once part. Today, more than seven hundred such slabs are known, and since the first half of the 19th century, they have consistently attracted the attention of researchers.

The carvings on the Bayil Rocks feature deeply carved inscriptions, organically combined with elegant floral ornaments and figures of humans and animals. The craftsmanship reflects the high level of professionalism of the masters of that time. The interplay between text and image is especially evident on a stone depicting the head of a buffalo — an example of harmonious unity between written and sculptural tradition.

On some slabs, the name of the master — architect Zayn-ad-Din, son of Abu Rashid Shirvani — has been deciphered. Among the carvings on Bayil Rocks, portrait depictions are particularly notable, executed with an unusual realism for that period. In total, twelve portraits of men and women have been discovered, which researchers believe reflect the images of notable figures of the 13th century. Of particular interest is a stone depicting a human head in full-face view with the inscription “Faribruz.” Scholars consider that the bas-relief may be a portrait of the Shirvanshah Faribruz, during whose reign this structure was built.

Motifs similar to the carvings on the Bayil Rocks are also found in other regions of Azerbaijan. These include depictions of animals — lions, leopards, bulls, deer, and gryphons — which adorned architectural monuments and mausoleums. A relief in a style close to that of the Bayilov slabs, showing the head of a bull, was discovered during archaeological excavations near the Maiden Tower in Baku. By artistic features, it belongs to a later period — the 14th–15th centuries — and represents a continuation of the developed tradition of Azerbaijani stone sculpture.

Despite decades of study, the Bayil Rocks remain one of the most enigmatic monuments of medieval Azerbaijani architecture and stone sculpture.

To be continued...

References:

Rasim Afandiyev

Abbas Islamov

By Vahid Shukurov, exclusively for Caliber.Az