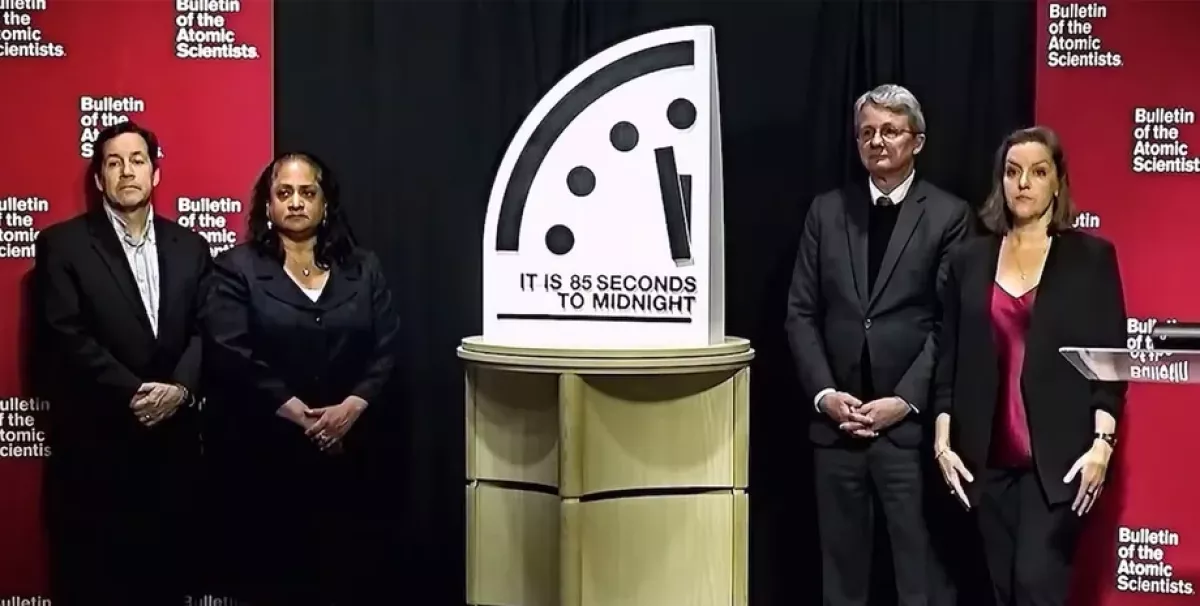

The Doomsday Clock: 85 seconds to midnight Reflections on the edge of global catastrophe

On January 27, 2026, according to the official press release of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, “the Doomsday Clock was set at 85 seconds to midnight, the closest the Clock has ever been to midnight in its history.” In this context, the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin (SASB), which sets the clock, called for urgent action to limit nuclear arsenals, develop international guidelines for the use of artificial intelligence (AI), and establish multilateral agreements to counter global biological threats.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is an American journal covering issues of international security and threats related to nuclear weapons, other types of weapons of mass destruction, climate change, and emerging technologies. The first issue of the publication was released in 1945 in Chicago—immediately after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

According to an editorial published January 27, despite last year’s warning, “Russia, China, the United States, and other major countries have instead become increasingly aggressive,” accelerating global competition on a “winner-takes-all” basis. This, the editorial explains, accounts for the clock being set at 85 seconds to midnight, marking “the closest it has ever been to catastrophe” in the history of the Doomsday Clock.

The article also highlighted other potentially catastrophic risks to humanity. Among them is the accelerating evolution of AI, viewed as a new form of biological threat due to the inescapable possibility of developing pathogens with it, against which humans would have no effective defense. In this way, the editorial warns that “the AI revolution has the potential to accelerate the existing chaos and dysfunction in the world’s information ecosystem, supercharging mis- and disinformation campaigns and undermining the fact-based public discussions required to address urgent major threats like nuclear war, pandemics, and climate change.”

Indeed, whether standing, falling, or even lying down, humanity seems increasingly paralyzed. Instead of moving toward unique progress—which, amid the unprecedented technological boom of our time, should not only be possible but a pressing necessity—humanity is edging ever closer to catastrophe.

In this context, one recalls the views of the outstanding American scientist of Serbian origin from the 19th–20th centuries, who made a significant contribution to the development of electrical engineering—Nikola Tesla. He envisioned an ideal world as “one without hunger and wars, which begin from the top, not the bottom.” In his view, “some start wars, while others fight them,” while the initiators remain far behind the front lines, feeling secure. Yet, Tesla wrote, if they knew that at any moment a bomb could be dropped on them by a plane “instantly moving through space and bypassing all defenses,” they “would think a thousand times before starting a war.”

Tesla believed that “there is no point in inviting death upon oneself.” Wars, he argued, would only end when a universal weapon—against which no defense exists—was created. He explained his position by comparing wars to gambling, where everything is staked for a potential win that demands sacrifices. Yet, he emphasised, if winning is impossible when both sides are doomed to lose, then starting a war is simply pointless.

Hence Tesla’s exclamation that the globe could be freed from deadly wars only if all nations possessed in their arsenals a “reliable weapon of incredible power, turning war from a contest into certain suicide.”

It is fair to say that the brilliant scientist and innovator reasoned logically, sensibly, and rationally, drawing, one might say, on elements of socio-geopolitical pragmatism. However, he did not live to see the advent of nuclear weapons, which, in essence, became the deadly reality for everyone.

Initially, nuclear weapons appeared in the hands of a single country, but soon a number of major world powers acquired them. Following Tesla’s logic, their mere possession by the largest nations should have cooled the belligerent ambitions of their political elites.

However, as we can see, the opposite is occurring—at least in terms of rhetoric surrounding the threat of nuclear weapons. At the same time, it is already clear that there can be no winners in such a war. Moreover, even today, military conflicts—though not involving nuclear weapons—are unfolding in various regions of the world, claiming tens of thousands of innocent lives.

Some might be quick to conclude that Tesla’s prediction was wrong. Yet we should not jump the gun. After all, it is possible that the “nuclear rhetoric” will never lead to the actual use of this deadly weapon. And in that case, the world may still come to appreciate the accuracy and depth of the great scientist’s analysis.

To conclude, let us recall another of Nikola Tesla’s statements, which opens a space for reflection on a completely different vision of life—one governed not by fear and threats, but by optimism and hope for the future for all. In his words, most people, being deeply absorbed in the study of the external world, fail to notice what is happening within themselves. Meanwhile, “the highest aim of human development is complete mastery of the mind over the material world,” in which the forces of nature are harnessed to satisfy human needs.

Let us leave it there for now… and perhaps take a moment to reflect.