Türkiye’s growing role in the new Middle East Alliances, defence, and diplomacy

This week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Alongside the weakening of the collective West, regional powers are increasingly playing a significant role in global politics. In the Middle East, Türkiye’s importance is growing, as it has recently achieved new international successes. It has effectively eliminated a potentially dangerous source of threat to its security in the form of the Kurdish separatist entity in northern Syria, despite its backing by the United States. Türkiye has also successfully prevented attempts by Greece to create a threat to its access to the sea, even though the Greeks enjoy support from the EU. Ankara’s successes in neutralising threats linked even to major external actors are complemented by its progress in building a powerful alliance that includes Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan.

A new regional alliance emerges

On February 3, President Erdoğan met in Riyadh with the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. This was a remarkable event, especially considering the relatively recent disputes between the two countries, in which Türkiye, alongside Qatar, opposed the Saudis. However, due to the ongoing weakening of the West, Saudi Arabia has in recent years been pursuing a more multi-vector policy, which has included not only reconciliation with Iran and a strategic partnership with China, but also a strengthening alliance with Türkiye. Riyadh and Ankara are increasingly discussing regional and global issues, as it is around Ankara that a significant part of the new Middle Eastern configuration is taking shape.

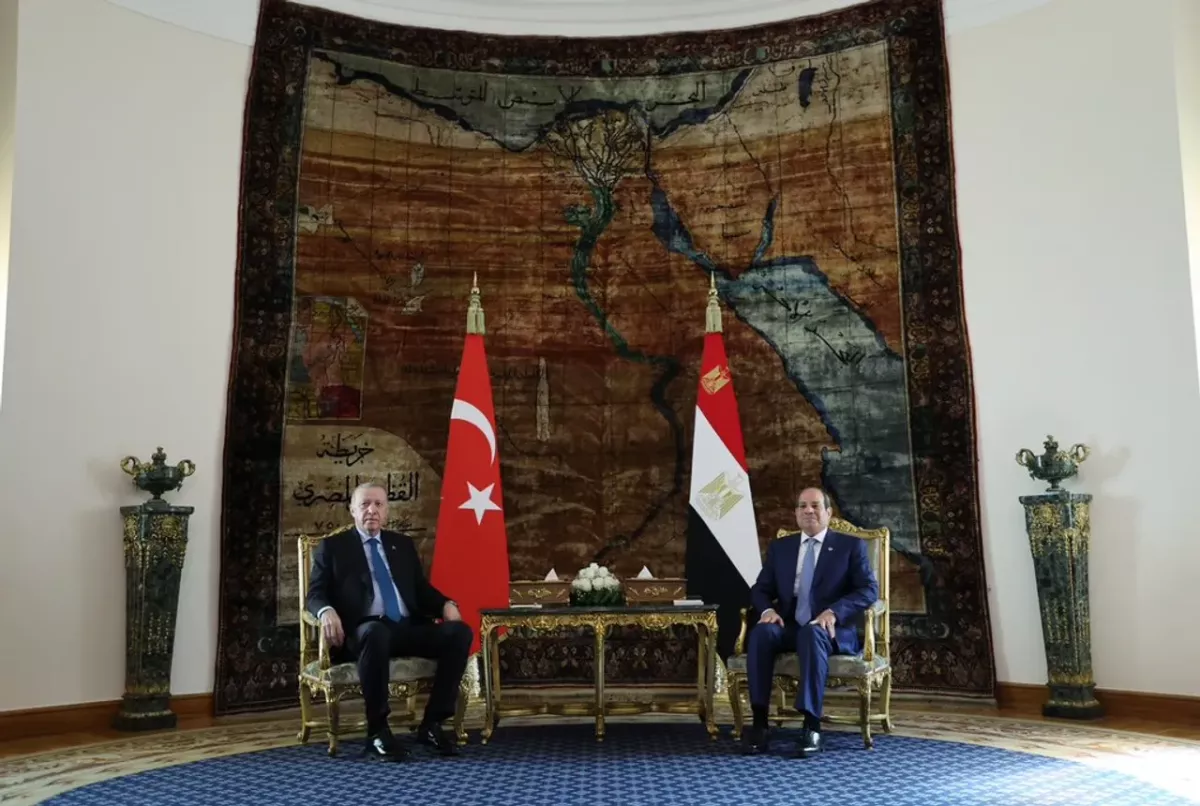

This was further evidenced by the fact that, the day after his talks with the Saudi leadership, Erdoğan met in Cairo with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Their discussions were not limited to pragmatic plans, such as increasing trade turnover from $9 billion to $15 billion, but also covered coordinated actions on Gaza, Libya, Somalia, and Syria. In other words, Türkiye is working closely with the largest Arab state. As Ankara continues to build a regional alliance involving Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, there are strong reasons to expect that Egypt may also join.

News of negotiations on a trilateral defence alliance between Türkiye, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia emerged about a month ago. Its origins can be traced to the September mutual defence agreement between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, which, in its structure, mirrors the foundational legal framework of NATO. Türkiye’s potential accession to such an alliance is not far-fetched.

Talks of a military alliance in this configuration have been ongoing since 2015. Even then, noticing signs of Western decline, Türkiye and Saudi Arabia began building their own partnership, cooperating across the Middle East. Riyadh, in particular, helped Ankara strengthen the Syrian opposition by funding arms purchases, while the Saudi Air Force operated against ISIS from Turkish airbases.

Erdoğan’s recent talks with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman indicate continued rapprochement and notable progress in forming a regional bloc. The agreements reached go beyond economic cooperation between these two key Middle Eastern countries. In the current tense international environment, defence agreements are especially important for the creation of a new regional structure and the development of a regional alliance. Specifically, it was decided that Riyadh would join the programme to build Türkiye’s fifth-generation fighter jet, KAAN, contributing not only financially but also participating in production. As the Turkish president noted: “We have received a lot of positive feedback on Kaan. There is a joint investment with Saudi Arabia in this area, and we can implement this partnership at any moment.”

KAAN made its maiden flight in early 2024, with serial production scheduled to begin in 2028. Last year, Indonesia signed a contract to purchase 48 Turkish fighters of this type, giving new momentum to its production. All of this will enable regional countries to create their own alternative, depriving superpowers of the ability to arbitrarily pressure Middle Eastern states on defence matters — as the United States attempted with the supply of F-35s to Türkiye, which had already been partially paid for.

US and EU cannot dictate terms to Türkiye

During this week’s talks, Türkiye and Saudi Arabia also agreed to cooperate on the reconstruction of Syria and discussed the situation in the Gaza Strip, Yemen, and East Africa. This is a significant scope of engagement, based not only on the potential of the two countries but also on the real dynamics of their activity in the region.

Syria provides a clear example. Under Erdoğan’s leadership, Türkiye has, in just over a decade and a half, achieved what previous Turkish administrations had struggled to accomplish for more than half a century. It has fully dismantled, along its southern border, an Arab nationalist regime that for decades opposed Ankara — initially supporting Armenian, and later Kurdish, nationalists who attempted to wage war inside Türkiye.

Instead of the Assad Jr. regime, which collapsed at the end of 2024 despite support from Russia and Iran, a government came to power in Damascus that is widely considered close to Ankara. This proximity is rooted in years of prior partnership in opposing the Assad government.

Another step in consolidating a pro-Türkiye balance within Syria was the recent move by the Syrian government to dismantle so-called Rojava — the Kurdish separatist entity in northern Syria. It was established in 2012 by remnants of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) nurtured under Assad Sr.’s regime. The PKK, designated a terrorist organisation by Türkiye, repeatedly announced ceasefires, restructuring, or even disbandment over recent decades, but continued to wage war against Türkiye, simultaneously selling its services to the United States in operations against US opponents in the Middle East.

As a result, after the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, the PKK effectively created its own quasi-state in the north under the protection of the US and other NATO countries, from which operations were conducted against another NATO member, Türkiye. That is what NATO “partnership” looks like in practice!

In general, dealing with the separatist entity Rojava was not easy. In 2018, when Russian forces in the form of the Wagner PMC attempted to enter its territory — where Kurdish fighters were extracting oil, which funded their operations — they were met with a storm of fire, including American air and artillery strikes. Around one hundred Wagner mercenaries were killed, a fact that is rarely recalled in Russia. After that, the Russians avoided further action against the Kurdish fighters.

Türkiye, however, was unwilling to tolerate the existence of this bantustan in northern Syria, beloved by the West’s so-called “new left” and liberal circles. Gradually, by limiting the manoeuvring space of Kurdish groups through military operations and diplomatic steps, and by strengthening the new Syrian government, Ankara achieved its objectives.

On January 30, fighters of the former PKK were forced to hand over their military and civilian structures to Damascus and allow Syrian government troops to enter territory previously under their control. This was not a mere formality; it demonstrated Ankara’s influence. Even at that point, the battered Syrian PKK branch still had three armed brigades and a weakened but persistent residual American support. Because of this, Damascus had to attempt negotiations with Rojava leaders three times — a sharp contrast to its dealings with the Alawites, with whom no serious negotiations were ever conducted.

Since the 2000s, the collective West had relied on former leftist Kurdish groups, particularly the PKK, as instruments of broader disruption in the Middle East. Türkiye has broken that game and continues to do so. In effect, Erdoğan has forced the West to accept the elimination of the PKK’s main centre in Syria, even as Western powers and their allies attempt to employ Kurdish fighters in Iran.

Additionally, the United States is reducing its military presence in northern Syria to a minimum, while Russia is withdrawing entirely — the so-called “heroic Rojava” relied entirely on the firepower of its Western allies and its ability to manoeuvre between the West, Russia, and the Assad regime. All of this is now gone. Once again, Erdoğan’s government has achieved the elimination of the last outpost of subversive forces along Türkiye’s southern borders not only through consistent military pressure — previous Turkish governments had attempted to stop cross-border threats by force — but also through political and diplomatic measures.

That this represents a consistent strengthening of Türkiye’s influence in the Middle East, rather than a coincidence, is evident from another recent episode in international politics, where Ankara successfully defended its interests despite pressure from another global player, the European Union.

Recently, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis threatened to exclude the Turkish government from EU civil programmes if Türkiye did not accept the expansion of Greek territorial waters in the Aegean Sea.

Given the numerous small Greek islands off the coast of economically developed western Türkiye, including Izmir, this expansion — from 6 to 12 nautical miles — would severely restrict access to the sea for key Turkish economic centres. Türkiye would lose access to 80% of the Aegean Sea’s waters. Moreover, the Greeks are acting unilaterally, citing the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea as justification for the expansion, even though Türkiye never signed the treaty.

Therefore, Ankara immediately warned that any attempt by Athens to cut off its access to the sea — crucial for international maritime communications — would be considered grounds for war. Greece has sought to push through the expansion of its territorial waters across multiple areas, but so far has only succeeded in the Ionian Sea in 2021, where it did not significantly affect the interests of other states. In the Aegean, however, it has failed, despite blocking Türkiye’s participation in EU military programmes.

Athens has not dared to take more radical steps, recognising that a financially weak and militarily limited Greece has no chance in a confrontation with a rising Türkiye, whose influence in the region continues to grow. Its only remaining strategy is to leverage the EU — but, as experience shows, Ankara has no fear of even that.

Of course, the current steps by Türkiye and other Middle Eastern states to build new alliances are largely a response to the breakdown of the international system and the intensifying global confrontation. This explains their strong focus on defence issues. But it would be a mistake to see all of this as merely cynical calculations and schemes. In any case, Middle Eastern leaders have far more moral legitimacy to reshape the international system than the global liberal establishment, which has often masked not only its own lack of principles but also outright corruption — recently exposed once again through revelations connected to parts of the Epstein case.

No one is an angel, and the Middle East is governed by people of the same human calibre. Yet what is particularly striking is that, against the backdrop of increasingly indifferent global superpowers and their allies toward issues that threaten humanity’s very survival, the emerging Middle Eastern bloc demonstrates a far more responsible approach compared to the collective West.

In particular, during the talks between Erdoğan and Mohammed bin Salman, the importance of adhering to the principles of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement was emphasised, as well as the need to develop further climate accords. In November, Türkiye will host the 31st Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP31) in Antalya — one of the previous rounds, COP29, having taken place in Baku the year before last.

This is not just rhetoric and meetings — the concrete agreements between the Turkish and Saudi leaders included steps in this direction. For example, a renewable energy cooperation agreement was one of four agreements signed during Erdoğan’s visit to Riyadh (the others covered justice, the peaceful use of outer space, and research and development cooperation).

Thanks to Saudi investments of $2 billion, two large-scale solar power plants will be built in Sivas and Kahramanmaraş, with an initial combined capacity of 2,000 megawatts.

Attention to such issues is critical because, for the majority of humanity and most countries in the world, the current Western approach is unacceptable and dangerously inadequate. Amid the collapse of hypocritical environmental policies and the façade of a so-called “energy transition” promoted by liberal Western regimes, the task of energy transformation and planetary environmental protection remains urgent. Countries that take up the banner of humanity’s survival — through climate and environmental protection, fighting hunger and disease, reducing poverty, and pursuing sustainable development — can position themselves as leaders of humanity and help build a new world.

Conclusion

It is clear that the new Middle East will increasingly be shaped in the capitals of the region, and less in the centres of the old world powers. As we have seen, these powers are gradually coming to terms with their own weakness and prefer not to insist on their former positions. Moreover, they increasingly need to cooperate with regional powers themselves.

A symbolic trend of recent weeks illustrates this well: tankers heading to or from Russian Black Sea ports are hugging the Turkish coast in search of safety, because outside Turkish waters their fate could quickly become very precarious under attacks from Ukrainian forces. At the same time, the United States has stopped short of war with Iran, recognising that regional countries — even close US allies — do not want this conflict. All of this is a predictable outcome of the attempts by superpowers to shape the world while ignoring other countries. Their old world is collapsing, and the overwhelming majority of humanity has no reason to mourn it.