The Arctic as a bargaining field How NATO, Europe, and Trump navigate Greenland

One of the notable recent geopolitical developments is NATO’s “Arctic Sentry” initiative, proposed by NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte on February 12 during a meeting of the Alliance’s defence ministers (the U.S. Secretary of Defense did not attend). The timing is significant: this announcement came just one day before the Munich Security Conference, serving as a key prelude to the forum and aiming to firmly close the topic of Greenland from the perspective of the region through the American lens. Rutte cited “Russia's increased military activity and China's growing interest in the High North” as the rationale behind the initiative.

As a result, several think tanks quickly interpreted NATO’s move as driven by European leaders’ desire not to antagonise U.S. President Donald Trump, who has openly shown a geopolitical “interest” in Greenland. On the same day—February 12—Politico suggested that “NATO deploys to Greenland to keep Trump onside,” portraying the new initiative as a “rebranding exercise aimed at mollifying the U.S. president — in response to a largely exaggerated threat.” In this light, the Alliance’s growing Arctic presence appears aimed “less to deter Russia than it is to deter Donald Trump.”

Naturally, in light of Rutte’s initiative, experts immediately revisited the days of the January Economic Forum in Davos, during which nearly all of Europe was awaiting Trump’s declaration of his “final word” on Greenland in Switzerland. Yet, as if by magic, the so-called “American threat” to Denmark—and to Brussels in general—was instantly neutralised. As Donald Trump noted on his social media page, he and Mark Rutte had succeeded in laying the groundwork for a future agreement on Greenland and the entire Arctic region, which, if realised, “will be a great one for the United States of America, and all NATO Nations.”

Following the immediate aftermath of the Davos Forum, NATO, through its spokesperson, announced that upcoming negotiations among Alliance members would focus on Arctic security, primarily aimed at ensuring that Russia and China cannot establish a foothold in the region, either economically or militarily.

Mark Rutte himself emphasised NATO’s critical role not only for Europe’s security but also for the defence of the United States. As he stated, the security of the U.S. depends on the safety of the Arctic, the Atlantic, and all of Europe. In a move typical for him, the NATO Secretary General highlighted the importance of President Trump, describing him as right in urging Brussels to do more to protect the Arctic from Russian and Chinese influence.

Rutte also reassured that American allies in Europe have plans to take on greater responsibility for their own defence, including strengthening their role within NATO. As a result, the U.S. will continue to maintain a strong presence in Europe both in nuclear and conventional terms.

According to Rutte, this is logical because Europe represents a significant segment of the world, including economically, so the focus is on greater leadership in defence. Over time, he added, joint commands will be managed by Europeans.

Currently, NATO is developing new initiatives related to Arctic security, particularly the security of Greenland. Rutte described this as crucial, noting that, in his view, Russian President Vladimir Putin would be interested in a European defence system operating independently of the Alliance.

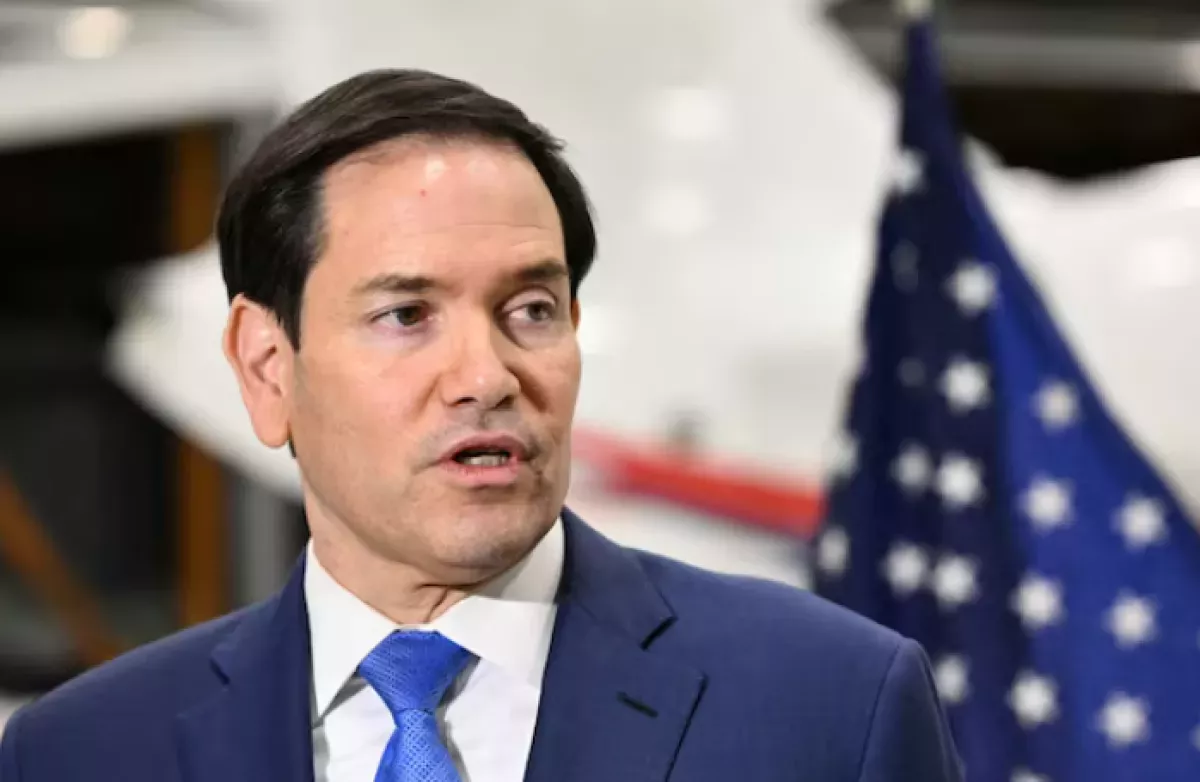

In this context, NATO’s announcement of the Arctic Sentry initiative just before the opening of the Munich Security Conference was clearly far from a spontaneous move. Analysts have also emphasised the seemingly “peaceful” tone of U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s Munich speech, which framed Europe–U.S. relations through the lens of historical ties and close NATO cooperation. Notably, unlike at Davos, Greenland received almost no mention during the Munich discussions.

From this, some observers have drawn a rather interesting conclusion. Considering that the world has become accustomed to a familiar pattern in Trump’s approach—initially issuing overly threatening statements toward a country or organisation, then softening his stance by proposing the possibility of a “fair deal,” and finally agreeing to endorse outcomes that satisfy him—the resolution of the “Greenland crisis” can be understood within this same framework. At least, this appears to be the case in the current historical context.

In other words, according to proponents of this interpretation, Trump was initially satisfied with a scenario in which Europe would assume direct responsibility for a significant portion of Arctic security, with Greenland serving only as a peripheral aspect of the broader picture (albeit under U.S. oversight). However, European leaders’ reluctance to give up their accustomed “way of life,” relying primarily on Washington’s financial backing for global affairs, pushed Donald Trump toward an ostensibly forceful—albeit initially rhetorical—approach regarding Greenland.

When Brussels began to perceive Trump’s threats as more than mere rhetoric and sensed a real “fire under the table,” the European Union decided to take action—or at least to assert itself as independent and strong partners, albeit through NATO.

But wasn’t that exactly what Trump wanted? An interesting geopolitical subplot, however, emerges around Mark Rutte’s announcement of NATO’s “Arctic Sentry” initiative, doesn’t it?